Telling the Jewish story provokes more questions than it provides answers. And that precisely how we sustain and enliven ourselves as we add to the tale. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

Vered Aviv holds a doctorate in Neurobiology from Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Her postdoctoral research has focused on the levels of calcium ions in neuroblastoma, measured using fluorescent dyes and a scanning microscope. She is also a dancer and currently serves as Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Dance, Academy of Music and Dance in Jerusalem. And Aviv is an artist. Her work has been exhibited in Israel, England and the United States. She functions at the intersection of science and art, as a practitioner and a researcher.

In 2014 the National Center for Biotechnology Information, part of the National Institutes of Health, published an article by Aviv: “What does the brain tell us about abstract art?” After reviewing studies using MRI imaging and EEG methodology, Aviv notes that the eyes of participants looking at a variety of styles of paintings scan abstract art differently. When looking at abstract art, the human brain does not engage its object-related systems as much. It is less activated to seek out the familiar. She writes: “Abstract art may therefore encourage our brain to respond in a less restrictive and stereotypical manner, exploring new associations, activating alternative paths for emotions, and forming new possibly creative links in our brain.”

The sensory-disruptive moment known as the giving of the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai contains at its beginning these words: “You shall not make for yourself a graven image…” In the theological and ethical context of the Ten Commandments, that instruction seems to be specifically a prohibition against idolatry.

Read in the context of Aviv’s research, however, it can also be understood as an insistence that living in attunement with divine resonance requires utilizing a different part of our brain, one that does not immediately default to the familiar. We are to perceive creatively, “explore new associations” and form “new possibly creative links in our brains.”

Visual arts provide a form of storytelling. Representational art presents a narrative using objects and settings that are familiar and readily identifiable to us. Abstract art also offers a narrative. It just does so differently.

Suhail Mitoubsi is an abstract painter based in the Teesside region of North East England. Mitoubsi explains that his paintings tell a story as much as representational paintings do. It is just that they explore and narrate a different realm: “Storytelling through abstract painting is all about using visual elements to create narratives that go beyond what we can see in the real world.”

For abstract artists, it is not only what is being explored that is different. It is also the intended affect on the viewer that is different.

Roberto Pignataro was an Argentine artist, who was particularly engaged in that country’s art movements during the mid-twentieth century. During that time avant-garde visual artists in Argentina used manifestos, public statements and essays to supplement their visual works as expressions of opposition to entrenched centers of political power. Pignataro was skeptical of that approach. He believed that visual art was most impactful when crafted to evoke meaning from the viewer rather than as a vehicle to deliver meaning to them.

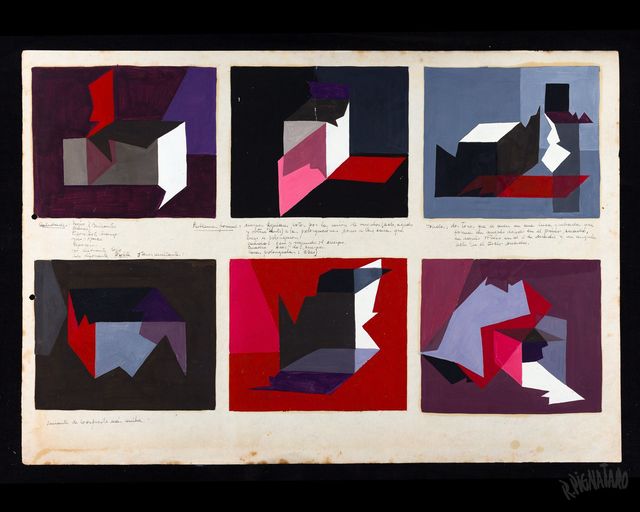

In contrast to artists who provided prescribed answers to viewers, Pignataro related to viewers not as passive observers but as vital co-authoring partners in the artistic venture. Pictured here is one of his earlier works, a study in light and color. It presents in a panel-based layout, a series of scenes with similar shapes that rearrange themselves over the course of the canvass and appear in different lighting and background moods. The layout emulates dynamic art forms such as the cels of cartoon and animated films.

The effect is that of an unfolding event. A narrative is revealing itself to us as we scan across and down the canvass. But it is one that challenges us to decipher what it is telling us. Pignataro engages us in an act of creative interpretation. And in the absence of an artist-defined narrative, different viewers will see different meanings. For Pignataro galleries can become not places merely for observation of an artist’s work. They can serve as sites of dialogue and discussion of viewers’ various interpretations. A community engaged in a mission of making meaning is created.

This week’s Torah portion, Ki Tavo, opens with an instruction for the Israelites to bring first-fruits as an offering once they have settled in the land of promise. In presenting those offerings one is to declare: “My father was a wandering Aramean” (Deuteronomy 26:5).

In the context of first-fruits, the readily identifiable meaning is that while the Israelites’ ancestors had once been nomads, wandering from place to place, the Israelites now had a land of their own, where they could plant and harvest. The ritual of first-fruits would have occurred during the festival of Shavuot.

The early rabbis, however, reimagined a different background for our Deuteronomy verse. Instead of setting it in a frame of Shavuot, they insisted that it be declared during Passover, at a seder, as part of the telling of the Exodus story. In doing so, the rabbis take the root letters for the word “wandering” and conjugate them differently and render them to mean “destroy.” On the canvass that is the Haggadah, the verse now reads: “An Aramean tried to destroy my father [but Jacob escaped and made his way to Egypt].”

The rabbis took a verse from Deuteronomy and estranged it from its familiar background. And instead of signifying a sense of arrival and settlement, it now describes the very start of Israelite exile. This rabbinic ambiguation of a sacred medium, words of Torah, challenges us to rise from mere passivity. No longer is anything plain and simple. We sit around a table as a community of interpreters, convoked to create meaning of this work of art. Is it a celebration of wandering resolved and the fruits that we can enjoy as settled beings? Or is it a warning of a new dislocation on the horizon?

Jourdie Ross is an abstract painter. She writes that she is often asked: How does abstract art tell a story? Her answer: “The painting holds the story. You tell the story.”

Our portion shares the same wisdom. Torah narrative has no life apart from our telling it. In describing how to the celebrate the fruit we derive from entering into the land of promise, the opening of Ki Tavo (“when you enter”) instructs us: “You shall tell the story this day before God that I have entered the land promised…” It is through our telling that both Torah and we live, in all of our creative possibilities.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) on Thursday September 19 as we explore tell the story.