To be present to one another is to become a site of revelation, where new possibilities are born. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

Last month I made a pilgrimage with my granddaughter Ruth to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. And there I confessed to her. I told her that while growing up I went to the museum several times a month and would regularly visit with Hortense Fiquet. Or at least with a portrait of her painted by her husband, Paul Cezanne.

Madame Cezanne sat for twenty-nine paintings by her husband. The one that resides in the Met is Madame Cezanne in the Conservatory. It is set in Jas de Bouffan, the Cezanne family estate near Aix and was painted in 1891. Hortense Fiquet, from a working-class family, met Paul Cezanne, the son of a banker, in Paris in 1869 when she was 19 and he was 30. Cezanne kept his relationship with Hortense hidden from his family, even after she gave birth to Paul Jr. in 1872. They did not marry until 1886, seventeen years after they first met. Cezanne died in 1906 and left Hortense out of his will. He was buried in Aix-en-Provence. When she died in 1922, she was buried in Paris.

When I would visit with Madame Cezanne, I would tell her about the events, and the feelings, of my life. And then I would listen to her. With her head tilted, hands folded in her lap and her flat, neutral expression, she appeared ready both to hear and to share in a quiet and non-judgmental way the most personal details of one’s life. She was available to know and to be known.

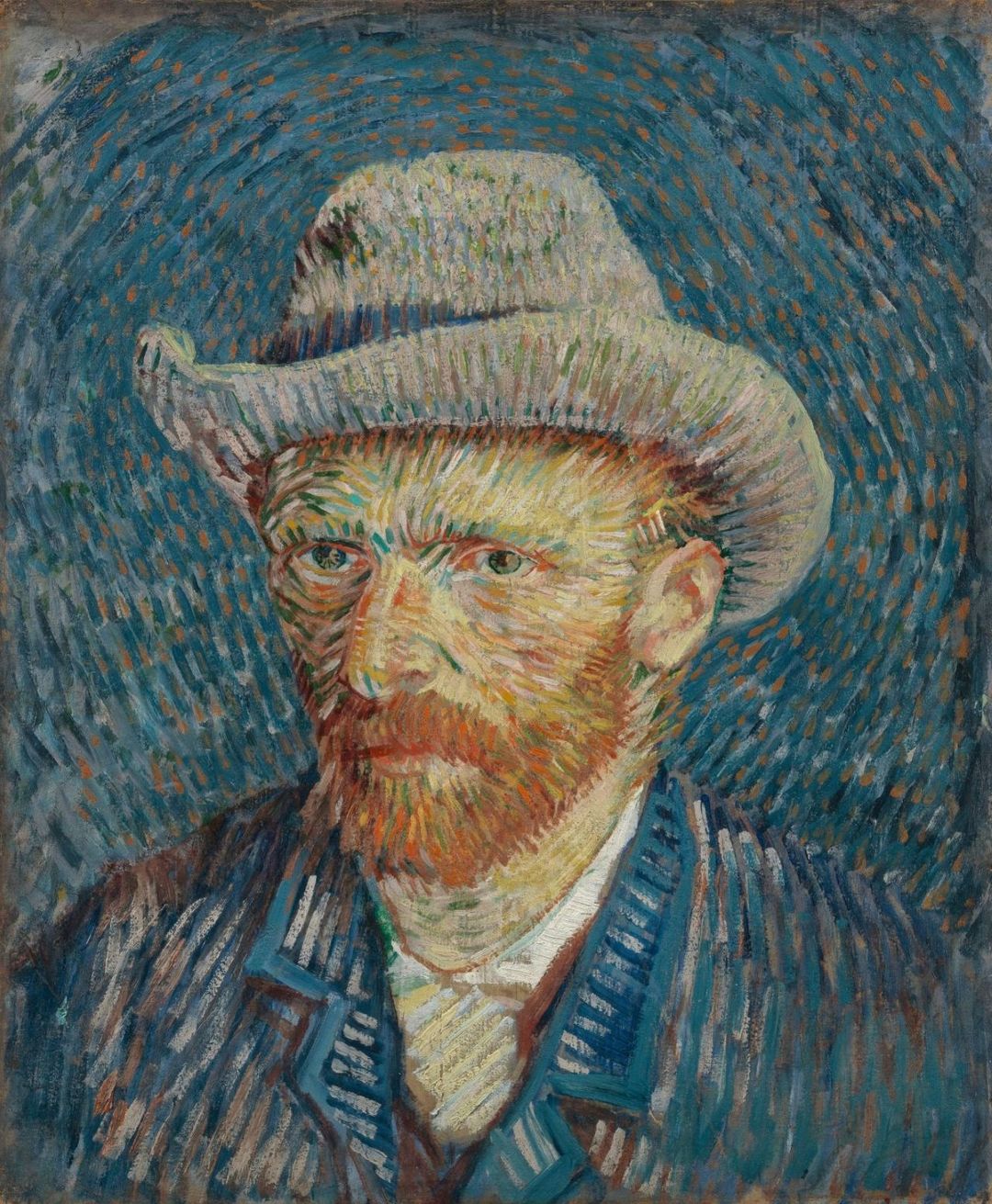

In the same wing where Madame Cezanne lives is a portrait of Vincent Van Gogh. It is actually a self-portrait, one of thirty-six that he did. Van Gogh is second only to Rembrandt in the number of self-portraits produced by an artist. But while Rembrandt painted about one hundred self-portraits over fifty years, Van Gogh did his over a period of ten.

Part of the reason for Van Gogh’s high number of self-portraits may have been financial. He was constantly short of money and frequently could not afford to pay a model. The painting displayed here was done on cotton canvass, a much less expensive material than linen. Yet, perhaps there is another reason. That Van Gogh suffered great mental pain and found long-lasting companionship difficult to achieve is well-known. As I stare into his eyes, I feel the anguish to be known.

To know and be known by being fully present before another lies at the heart of what revelation is all about in Torah. Parshat Yitro brings us to Mount Sinai, where God reveals Godself. The medieval commentator Rashi teaches that the Israelites brought about that moment through their yearning to know and be known. And when God does appear and speak, God says “You yourselves have seen what I have done.” Again it is Rashi who clarifies the text for us: There is a difference between getting a report about someone and being present to someone. The former allows for distance and skepticism to develop, the latter promotes attachment and compassion.

The moment at Mount Sinai does not inoculate the Israelites against feelings of anxiety, despair and grievance. It exposes them to what is possible, a way of living through the inevitable instabilities of life. Jewish tradition teaches that we were all at Mount Sinai, that we each carry within us that direct experience of being present to a desire of knowing and being known. We bear the knowledge of how to make our way forward.

Few of us are gifted with the incendiary creative talent that Van Gogh had to paint our unique selves. But all of us have the ability to be present to one another. When we are, we become sites of revelation and new possibilities are born.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday February 9 as we explore to be present.