The most enduring wisdom in Torah is found not in the explicit black letters but in the expanse of white space that surrounds them. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

In 1620 one hundred two men and women set sail from England seeking a new start and a better life for themselves in the New World of North America. The British crown had authorized them to settle in the colony of Virginia. They had in hand from the Virginia Company, a commercial trading venture sanctioned by King James I, a charter which defined the structure of government to be established there and the responsibilities of the Company to supply and support them.

Fierce storms drove their ship substantially off course. They landed at Cape Cod, an area not governed by the king’s grant or by the terms of the Virginia Company charter. In the absence of a document legitimizing their community, establishing rules of behavior and structuring a form of governance, they drafted their own: the Mayflower Compact. This was the first document establishing self-government in the New World.

By the time that King George sought to reimpose the crown’s sovereignty in North America one hundred fifty years later, self-government had become not only an established political system but also a cultural value that guided daily life and shaped the colonists’ view of themselves as sovereign human beings. Citizens were the source of law, not the king.

The American experiment in self-government over the last 400 years has been less encumbered by the weight of a national history or by traditions of aristocracy and intractable class barriers than the political experiments of European nations have been. In both its realities and its mythologies, America has promoted individual aspirations and possibilities, rewarded entrepreneurial enterprises and elevated the value of individual choice.

The desire for liberation from constraint and the need to create community sometimes come into conflict. One artist who experienced that intensely was Kazimir Malevich. Born to Polish parents in Ukraine in 1879, Malevich developed an interest in drawing by the age of twelve. In 1904 he moved to Moscow to attend art school. There he explored the modernist movements of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism and Cubism. His early paintings translated recognizable objects through the light, colors and geometry of those influences.

Early 20th century Russia was a hotbed of experimentation, both artistic and political. By 1915 Malevich had developed a unique style of painting that aesthetically overthrew any attachment to objective reality. His new approach, which he called Suprematism, abandoned figurative elements altogether and embraced pure abstraction. It was an art form that sought not to reflect reality but to transcend it. Bypassing the limitations of representational reality in favor of “pure artistic feeling,” as Malevich described it, the artist could bring the viewer into contact with infinite space, with the “the ineffability of the Absolute.”

Malevich’s project of overthrowing prescribed reality found a supportive political home in the Russian Revolution of 1917. In 1918, he joined the People’s Commissariat for Enlightenment as an employee of its Fine Arts Department. However, by 1930 his work had become suspect in the eyes of the Soviet authorities, conflicting with the officially endorsed style of Socialist Realism.

He was arrested in 1930, and in 1932 his paintings were displayed at an exhibition commemorating the 15thanniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution where they were labeled as “degenerate” and anti-Soviet. He died in 1935. His paintings were not exhibited in public again in Russia until the glastnost period of Gorbachev in 1988.

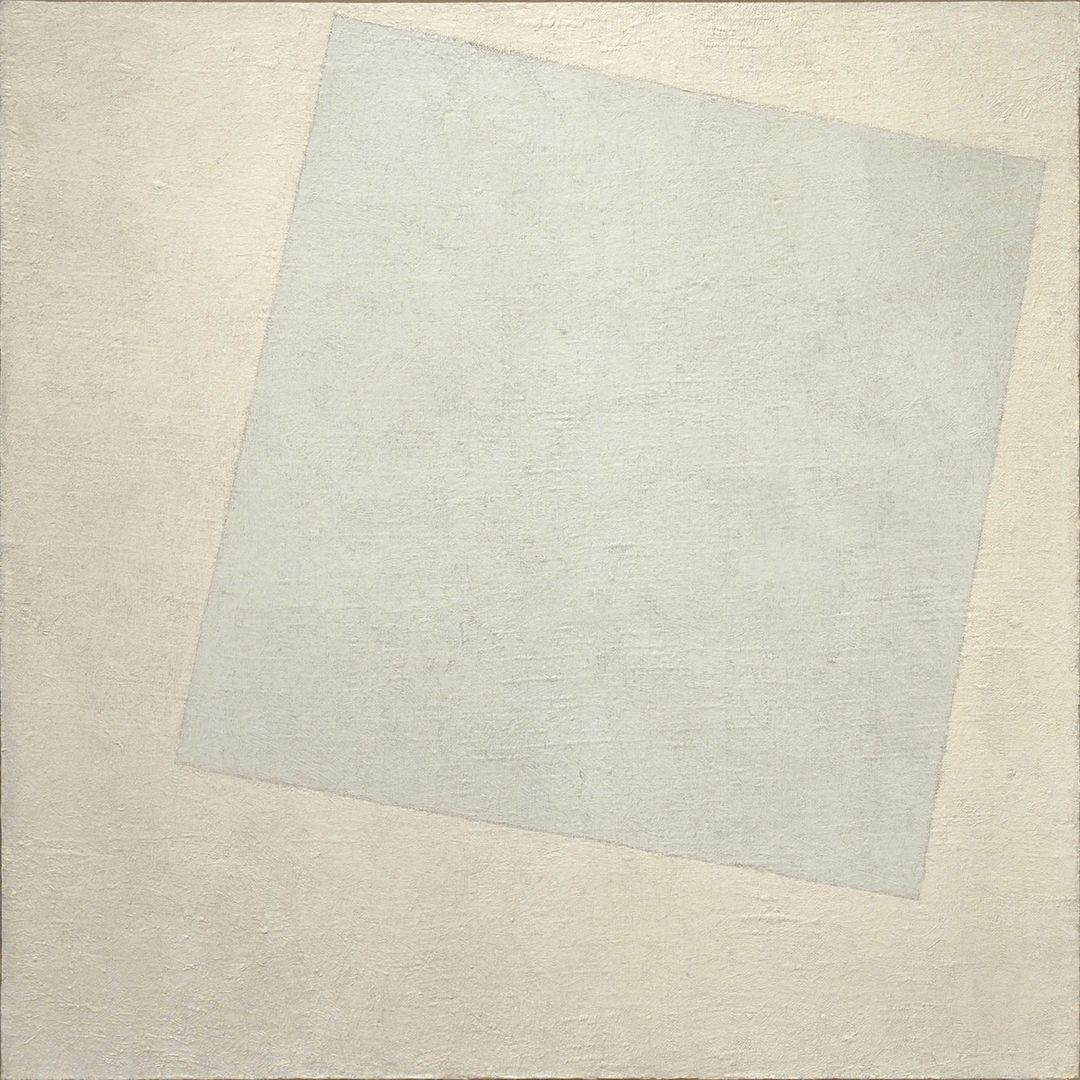

Pictured here is his work White on White, painted in 1918. The apparent simplicity of the image is belied upon a closer viewing. A white square floats atop another, larger white square. There is a dance and interplay at work. The top square has a cool shade to it, while the base square has a warmer undertone. Malevich used three different white pigments: lead white; zinc white; and titanium white. The top square is tilted, off-centered. The bottom square appears as stable, while the top one is seeking alignment, adjusting itself. Yet, what prevails is the absence of any objective figure. Minimalism describing the universe in its infinite expanse…and the fulness thereof.

Our Torah portion, Vayikra (“He called”), opens with the last letter of the first Hebrew word greatly diminished in size compared to the first four. It has much more white space around it, floating perhaps on their edge. Rabbinic literature describes the Torah as having been written as “black fire on white fire.” The black fire is the letters. The white is the space around them. The letters are revealed wisdom, proclaimed by the Source of all life. The white space consists of hidden wisdom. Its revelation awaits human curiosity, initiative and imagination.

The American colonists embarked our nation on a continuing experiment in the democratic ideal of self-government, where ordinary citizens are the sources of civic authority. Torah reminds us that the greatest wisdom it holds is that which we will uncover in our exploration of its infinite space. Kazimir Malevich painted fields taking us beyond what is evident to an encounter with the “ineffability of the Absolute.” In his painting White on White, white emerges not as an absence but as an infinite, timeless presence. Its exploration is up to us.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) on Thursday March 21 as we explore timeless presence.