Disorienting experiences can drive us deeper into old patterns. Or they can open us up to creative new possibilities.

View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

My very first day of rabbinic school was in Jerusalem. A few dozen of us had uprooted ourselves and crossed thousands of miles to a new country in an entirely different region in the world. The language we would be speaking and studying in for much of the time would be different than our first and familiar one. The school’s dean stood before us and said, “You are no longer living in the Occident. You are now living in the Orient. Time for you to get oriented.” Clever, I thought.

A year later, it was the last day of our first year of rabbinic school. Again, the dean of our Jerusalem campus stood before us. He wished us well on the next steps of our rabbinic school journey. I raised my hand. “Now that we’re leaving the Orient, shouldn’t we have a dis-orientation?”

Probably too clever by half, I thought. Still, leaving Israel and returning to the United States after a year did have its cultural re-adjustments. The shaking of hands, the display of a smile, how and at whom one gazed. These were different in the two cultures. Perhaps most of all, argument in the Orient was not the creation of division but the affirmation of a relationship. The cognitive shake-up stirred by these differences were as important in my learning as any of the textual material I would read over the next four years.

Separation from the familiar is a necessary and inevitable part of human development. A baby begins to recognize that they are a separate being from their mother around the age of six or seven months. It is an experience that can lead to anxiety. Loving and skillful parenting can provide the reassurance that helps the infant develop object permanence, the understanding that objects continue to exist even when they are not visible, heard, or touched. This becomes a key milestone in the infant’s brain development.

Moments of finding ourselves in unfamiliar environments or facing unexpected changes continue throughout our lives. What psychologists describe as “disorientation experiences” can cause us to feel threatened, anxious. It can lead to our clinging to familiar ways of thinking, our biases, ever more tightly. An alternative response is also possible.

Recent studies in learning theory suggest that disorienting dilemmas can lead individuals to critically examine their existing frames of reference. The brain becomes primed to sense new patterns of explanation and meaning. Brain-imaging studies of people evaluating anomalies, unsettling dilemmas, show a spike in activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, that part of the brain instrumental in adaptive thinking. Disorientation can birth creative thinking.

Lajos Tihanyi was born in Budapest in 1885 to a Hungarian Jewish family. At the age of eleven he contracted meningitis and became deaf and mute as a result. Tihanyi was drawn to the visual arts, but there was no fine arts academy in Hungary at the time. Instead, he attended the School of Industrial Art and Design. He became a self-taught artist and joined those exploring new art forms in Hungary.

The Hungary in which Tihanyi began his artistic explorations was a scene of upheaval. By his 24th birthday, the Hapsburg Empire, of which Hungary was a part, had collapsed after 700 years of control. Hungary lost territory with the end of World War I. A series of left-wing governments lasted less than a year. Ultimately right-wing forces, advocating “nationalist Christian” policies, gained control. Tihanyi fled Hungary in 1919 and eventually relocated to Paris, where he immersed himself in the modernist movements of Post-Impressionism, Expressionism and Cubism.

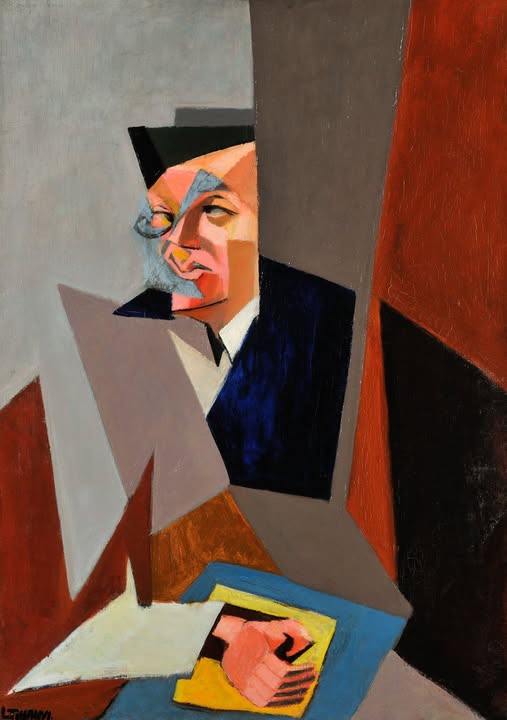

Pictured here is his portrait of the Romanian avant-garde poet, essayist and performance artist Tristan Tzara. Tzara was born in 1896 as Samuel Rosenstock. His parents spoke Yiddish as their primary language. As Jews they did not have legal standing as citizens until after 1918. Tzara resettled in Paris in 1919. He changed his name to one which in Romanian reads as “sad in the land.”

Tzara joined other artists in identifying the brutal horrors of World War as a product of the forces of science and rationality which had shaped modern life in the 19th century. They promoted art forms in which random associations would evoke a vitality free from the restraints of logic and tradition. Tzara himself became the co-founder of Dadaism, an artistic movement which promoted intentional irrationality and a rejection of traditional artistic, historical, and religious values.

Tihanyi’s portrait of Tzara is painted in the Cubist style. Cubism challenged the Renaissance depictions of space and perspective, which had dominated the art world for 500 years. Cubist artists fractured images into building blocks of their geometric forms. They revealed the dynamic arrangements and multiple dimensions that constitute any object or figure.

Modernists such as the Dadaists and Cubists intentionally sought to disrupt a chain of tradition and thinking that they identified as a source of destruction and dehumanization.

Parshat Vayigash (“he drew near”) climaxes a drama that has been building since the very opening of Torah. It has been speaking to us in a language that values ambiguity and the need for periodic disorientation.

Midrash aids us in understanding that Abraham becomes open to God not because of his blind faith but because of his readiness to question and even challenge the Source that powers the universe. Moses is precluded from entering the land of promise because he has become too routine in his responses to crises, not attuned enough to the call of the moment. The narrative of the entire Bible is structured around a series of exiles and returns and exiles. It is a never ending process.

Weeks ago in our Torah reading we witnessed Judah have a “disorientation experience.” He is confronted by his daughter-in-law Tamar. Disguised as a prostitute, she had had sex with Judah because of his failure to fulfill his responsibility and promise to allow his remaining son to marry her.

Still disguised, months later she is brought forward before him for judgment as an unmarried pregnant woman. Tamar discloses her true identity, and thus that Judah is the father, only to Judah. Judah could have exercised his power as chief and imposed on her the death penalty, thereby both upholding tribal tradition and hiding his own complicity. Instead, moved by Tamar’s dignified call for justice, he surrenders authoritarian power and gains new life.

In Vayigash, it is Judah, who has experienced disorientation and the discovery of new self, who is able to “draw near” to Joseph and assist him during his own estrangement from the familiar. Judah speaks to a still-disguised Joseph about what the potential enslavement of Benjamin would mean to Jacob. Something in Joseph breaks. His imperial, authoritarian self dissolves. He weeps. The water flows. A new life for him and his family is born.

Moments of disorientation will happen. Major life events. Shifts in the culture around us. Changes in our physical setting. These can entice us to retreat into what we imagine the world used to be. Or we can explore the promise that is within each of us: that the world and we in it are ever ready to be made anew.

Join us here at 7:00 P.M. (PT) on Thursday January 2 as we explore estrangement and reconstruction.