When we find a way to simultaneously honor our past and critique the limitations in the present it has created, we shape a future iridescent with possibilities. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

Portrait of a Young Gentleman by Thomas Gainsborough

It’s hard to find someone who feels good about the present moment. A recent Gallup poll found that 18% of Americans are satisfied with the way things are going in the United States. That is about one-half of the 35% historical average. Among those who dwell discontentedly in the present are some who long for what they remember as familiar, who want to restore the past. For others, the present, and the past upon which this current time was constructed, is to be rejected for a yet to be tested and unexperienced future.

However, it is in the present where you and I currently live. Though not really, at least not exclusively. We carry with us a rich past: a family history, cultural myths and stories, our own personal experiences. And also within us are dreams, of how things might be different. Unlike most animals, we bear with us each day a temporal stew, of past, present and future. How best to manage those elements?

Joseph is endowed with the gift of vision. He sees what has not yet happened. That gift lifts him out of a prison cell and into a palace of power. He also is skilled in the ways of executive administration, able to translate plans into present reality. Yet, he also bears in him the past as a living reality. Its memories are ever with him. They are imprinted on the names he gives his sons: Manasseh (“God has made me forget completely my hardship and my parental home”) and Ephraim (“God has made me fertile in the land of my affliction”).

These distinct temporal dimensions come crashing upon Joseph when his brothers, who had sold him into slavery out of their bitter sibling rivalry toward him, appear before him, first for grain and then for the release of Benjamin. Joseph reveals himself to his brothers, proclaiming: “Do not be angry with yourselves for selling me here. It was to save lives that God sent me here. God sent me ahead to save your lives.”

Joseph reframes past events. He does this so that his brothers will not have to live under the oppressive burden of guilt for having sold him as a slave and deceived their father. In doing so, Joseph also frees himself from the bitterness of a haunting past, one that had caused him to estrange himself not only from his family but also from himself. That present reframing of the past opens up for the family a future rich with success, growth and well-being.

Kehinde Wiley was born in Los Angeles, raised by a mother who worked as a teacher and earned extra income by selling second-hand goods salvaged from people’s garbage by Kehinde and his five siblings. When he was 11, Kehinde’s mother enrolled him in a free art class. She took him to The Huntington museum, where he found refuge in the classic portrait paintings on display. He attended the San Francisco Art Institute and eventually won a scholarship to Yale. In 2001 he arrived in New York as an artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

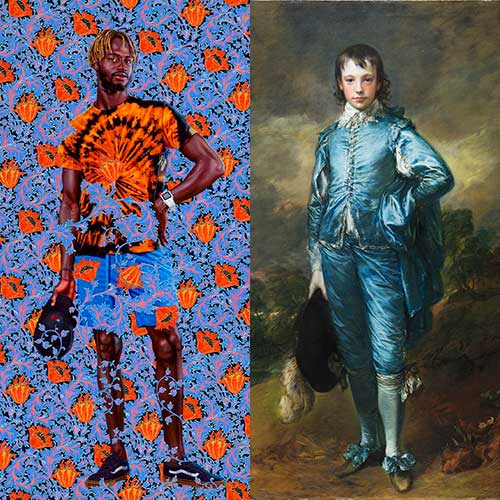

Pictured here is his painting A Portrait of a Young Gentleman. It is a reframing of Thomas Gainsborough’s A Portrait of a Young Gentleman painted in 1770 (also pictured here), which eventually became popularly known as Blue Boy. Wiley has reimagined Gainsborough’s privileged 18th century English aristocrat as a hip young 21st century Black man. The two paintings are virtually the same size, each approximately 178 cm x 115 cm. The figures strike the same pose, occupy the same orientation within the canvass, and each holds a hat. Is Wiley’s figure meant to displace as a retrograde irrelevance one from three centuries ago, or is something else at work here?

Gainsborough’s canvass is no less complex and challenging than Wiley’s. His Blue Boy is dressed not in the clothing of 1770 but in that which was in fashion some 130 years earlier. It signifies an homage to the artist whom Gainsborough considered one of the greatest, Anthony van Dyck, the Flemish artist who had died over one hundred years before. But there is more than a nostalgic looking backward in Gainsborough’s canvass.

As much as Wiley made his figure iridesce in orange and periwinkle, Gainsborough radiated his in Prussian Blue. This hue was a bold rejection of contemporary convention and an embrace of modernity. At end of the 18th century the leading portrait painter of the day and President of the Royal Academy of Arts, where Blue Boy was first exhibited, was Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds had declared that warm colors should be dominant and that blue should be relegated entirely to the backgrounds of canvasses. Gainsborough’s painting manages to simultaneously honor the past, critique the present and boldly foreground a new color, one first manufactured as recently as 1704.

Wiley’s A Portrait of a Young Gentleman hangs on a wall at The Huntington museum. Opposite it hangs Gainsborough’s A Portrait of a Young Gentleman. They face each other, in conversation across a room and across time. Both canvasses teem with respect for tradition, with critique of current limitations and with announcement that something new needs to be born in order to preserve the old.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday, December 21 as we explore reframing the past.