Surrendering our drive for total control over others gains us greater power than we ever imagined possible.

View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

Twenty-six versus two. That’s the difference between the number of symbols in the English language alphabet and those in machine language alphabet. The language with more options might seem likelier to be the more advanced conveyor of information. Yet, it is the simple binary system which has propelled us into the new information age. It has revolutionized the amount of information we can produce and store and the speed at which we can generate and transmit it. As a result, our world has become closer. And we can now explore worlds once beyond our reach, from outer space to the subatomic realms of electrons, protons and neutrons.

Recently, researchers have begun to investigate the impact of the digital revolution on the human organism. In an article published last year by the National Institutes of Health, three German scientists reported their findings that increasing digitalization has contributed to a rising prevalence of anxiety disorders and depression across the globe. Our expectation of being able to have constant answers to our questions can actually undermine our ability to function well in the world.

Michel Dugas, a professor of psychology at the University of Quebec, has pioneered studies on the relationship between valuing certainty and being vulnerable to various mental health challenges such as anxiety, eating disorders and depression. He created the term “intolerance of uncertainty” to refer to an unhealthy yearning for predictability. He found that individuals who scored high on a measure of intolerance of uncertainty were more likely to engage in narrow either-or thinking and to have maladaptive coping responses during times of crisis, such as denial, disengagement from life and substance abuse.

Dr. Dugas developed a therapeutic protocol for people with generalized anxiety disorder, which focused on reducing their aversion to not knowing. Those who completed the program suffered significantly less depression, and their levels of worry and anxiety fell to more normal levels.

Overcoming an intolerance of uncertainty is important not only for gaining relief from anxiety. Paul K. J. Han, senior scientist at the National Cancer Institute, has studied uncertainty as experienced by medical professionals. He has written about how accepting uncertainty can make us better thinkers and problem solvers. He advocates for developing “a culture of uncertainty tolerance.” A positive view of uncertainty promotes curiosity, flexibility and creative thinking. Not worrying about having all the answers can elicit from you answers you didn’t even know you had within you.

Michelangelo is considered the undisputed master of sculpting the human form. So attuned to the details of the human body was he that his marble almost becomes living flesh and bone. His statues are works of perfection.

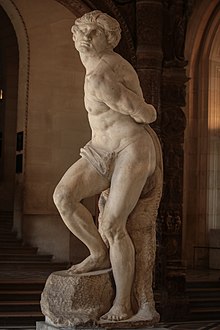

Yet, Michelangelo also created a few unfinished, imperfect pieces. Such a work of art is known as non-finito, a piece the artist has not brought to a completed state. One of Michelangelo’s non-finito sculptures is pictured here, The Rebellious Slave. The figure twists with a dynamic spiraling movement, his head tilted upward, as if he is stretching for freedom. His arms are tied behind his back. But his right shoulder is nearly nonexistent, and his right side is considerably incomplete and flat.

The unsettled, unresolved physical aspect of the statue is shared by its unsettled, dispossessed history of seeking a home where it might rest. In 1505 Pope Julius II asked Michelangelo to sculpt forty life-sized figures for an extravagant mausoleum. However, the pope delayed Michelangelo’s work on the mausoleum pieces by tasking him with other assignments at the Vatican.

When Pope Julius died in 1513, his heirs revised the original mausoleum’s plans several times. Those revisions excluded The Rebellious Slave, which Michelangelo had finished by 1516. In frustration, Michelangelo gifted the statue to a fellow Florentine, Roberto Strozzi. However, Strozzi, who had opposed the rule of Cosimo I de’ Medici, was exiled to France…and so was The Rebellious Slave.

The statue’s first home in France was the courtyard of the Chateau d’Ecouen near Paris. Some years later it was moved to Cardinal Richelieu’s palace in the west-central province of Poitou. In 1749 it was uprooted once again when the Duke of Richelieu brought it to Paris. After someone tried to illegally sell it in 1793, the statue was taken by the French government and made part of the Louvre’s collection.

As a non-finito sculpture, The Rebellious Slave, this figure contorting itself toward freedom, is an expression of Michelangelo finding fulfillment in incompletion. The beauty lies not in its perfection but in its ever emerging, ever evolving self. Michelangelo’s David, his Pieta inspire awe and reverence as the epic pieces they are. The Rebellious Slave touches us as the human we are: unfinished and ever on the way.

With Parshat Vayeshev Torah addresses our longing for resolution, for clarity. And it reminds us that the path to promise requires measures of doubt and disruption and perplexity. The previous portion ended with over forty verses describing in orderly fashion the line of Jacob’s brother, Esau…a line that would produce some of the Jewish people’s fiercest enemies. Those verses end by describing Esau’s line as “settled.”

Vayeshev opens by describing Jacob as also “settled.” But in describing Jacob’s line, the first son mentioned is not the oldest but the youngest, Joseph. It signals for us that Jacob’s life will not be settled. A rivalry between Joseph and his brothers son erupts. They throw him into a pit and sell him into slavery. He is taken down into the exile that is Egypt, where he is imprisoned.

The portion ends with a fellow prisoner, Pharaoh’s chief cupbearer, betraying the assistance Joseph had provided him while they were imprisoned together. Once the cupbearer is free, “He did not think of Joseph. He forgot him.” The very last words of the portion.

The early 19th century Hasidic rabbi Mei HaShiloach comments on the ironic opening of the portion, “Jacob settled,” by writing that the sacred journey requires not perfect clarity, freedom from doubt or quietude. Quite the opposite. One must, he writes, move continually into life’s uncertainties and search out the next wrestling between one’s higher and lower selves. “For God wants human acts,” Mei HaShiloach writes, “and in this world human beings must act in love, in ways that are not completely clarified.”

Torah reminds us that we cannot hide from the crises that are part of being human. Our yearning for total certainty is the disease a spiritual path is designed to overcome. About his sculpting process Michelangelo said: “I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.” The angel he set free in The Rebellious Slave is not the image of ideal beauty and perfection demanded by Renaissance standards. But a bound, half-realized figure struggling to break free. It is you and me.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) on Thursday December 19 as we explore the beauty of uncertainty.