To live our questions, rather than rush to answer them, becomes their own resolve. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

When Rabbi Harold Kushner wrote his now classic book following the death of his son at age 14 from the rare degenerative disease Progeria, he did not title it “Why Bad Things Happen to Good People.” He chose “When Bad Things Happen to Good People.”

Various faith traditions have sought to explain suffering as having a divine rationale: a test of faith; a consequence of sin and misbehavior; a spur to make us stronger and better people. Rabbi Kushner, instead, wrote through his personal loss and sorrow using the wisdom found in Jewish tradition: randomness and chaos course through this world, and we become more human not by increasing our sense of victimhood but by increasing how we take responsibility for ourselves and our world.

The entire Jewish Bible, from its opening to its closing words, is an epic tale describing an ongoing cycle of exile and return, of destruction and rebuilding. This cycle also describes the shape of Jewish history: the Roman conquest; the Spanish Inquisition; the pogroms of Eastern Europe; the Holocaust; Hamas terror. The responses of the Jewish people to these cycles of suffering has not been to complain or to enwrap in victimhood. Instead, the Jewish people built a complex system of communal institutions, adapted to a changing world, and innovated new avenues for livelihood and wealth.

The design of Torah is to train us to live in the world as active participants in its ongoing creation. It does this by both the content and style of its narrative. The overarching story line is one of movement toward a dimension of freedom and responsibility. Torah tells this story by leaving out many details. The inner life and motivations of the main characters are not provided. The Torah scroll is written without vowels or punctuation. Much of the Hebrew language is rich with ambiguity. The effect is to enlist the reader in constructing the text’s meaning.

And Torah’s design has its effect beyond the text. We close the book, roll up the scroll and walk back into the demands and challenges of everyday. We become, perhaps imperceptibly, practiced at reading our daily lives as we do Torah’s passages: no longer passive observers but active creators of our own lives. It is a triumph of sacred artistry.

The Renaissance painter Caravaggio was no saint, but he knew how to draw viewers into an active encounter with the sacred. A gifted painter, he was also a man of tempestuous temperament. Ever ready to get into a fight, he was arrested numerous times for, among other things, illegally carrying a sword in Rome, attacking the police, throwing food at a restaurant, and injuring a guard. He engaged in a duel, fatally wounding his opponent, which caused Caravaggio to flee Rome until he was able to obtain a papal pardon.

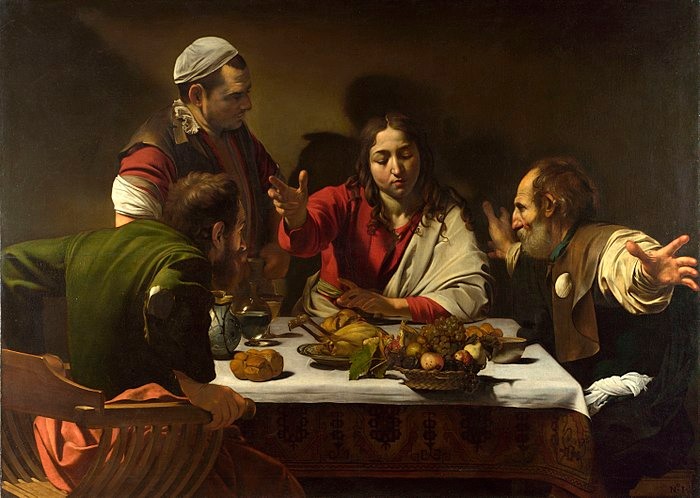

Pictured here is his painting The Supper at Emmaus. The subject is the story from the Gospel of Luke, which tells of the encounter by Luke and Cleopas with Jesus sometime after his crucifixion. They do not recognize Jesus until he blesses the bread at their meal at an inn. That is the moment Caravaggio chose for his rendering of that story, one described in different ways by a variety of artists, including Rembrandt.

At the table with Jesus are Cleopas on the left and Luke on the right. Cleopas is pushing himself up from his chair in panicked astonishment at the disclosure of the stranger’s identity. Luke flings his arms out wide. This is a moment of revelation. And Caravaggio has designed the image to draw viewers into the awe of that epiphany.

Bringing us into the picture is a basket of fruit. Perched precariously on the edge of the table, the basket may tumble off, perhaps even out of the painting all together. Caravaggio presents us with an opportunity: extend your hand, catch the basket before it falls; pull up a chair, there’s room at the table for you.

Though hard to see, there is a stray piece of wicker sticking out from the basket. It appears to be in the shape of an Ichthys, an ancient encrypted sign of Christian identification and belief. That coded symbol of participation in faith is echoed by the silhouette cast on the tablecloth by the pile of fruit. It appears as the tail of a fish, which is how the Ichthys was typically drawn. The viewer is given the sign of faith, an invitation to enter into that intimacy is extended. Whether the viewer chooses to accept the invitation is up to him or her.

Caravaggio elevates a scene familiar to readers of the Gospel of Luke beyond a passive viewing into something urgent and active. The viewer is invited in, is needed even, lest the fruit fall. Caravaggio has made it easy for anyone, including those from the most common backgrounds, to join the scene by his techniques, which violated conventions of Renaissance aesthetics. He refused to idealize sacred mythology. To the horror of many, he used ordinary working people with irregular, rough faces as models for his saints and iconic religious figures. What others sought to elevate, Caravaggio brought to a recognizable human level. The moment of spiritual revelation becomes not one enshrined in religious canon but one that is happening right now. With us present.

This is what Torah has done in this week’s portion with Rebecca. Until this week we have been reading, observing and critiquing the behavior of multiple characters moving across a page. Parshat Toldot opens with Rebecca pregnant with twins, who are contending within her. She cries out, “Lameh zeh anochi,” which as a question can be rendered as “Why is there this ‘I’? Why do I exist?” Rebecca is the first biblical character to question the limits and meaning of her subjectivity. That questioning propels her to go in quest of God.

The Hasidic commentary Mei HaShiloach notes that Rebecca has not used the more typical first person pronoun ani, but the more formal anochi, the pronoun God uses at the revelation at Mount Sinai. Rebecca’s birth-giving becomes associated with the divine procreative experience in the wilderness of birthing a nation. In that way, lameh zeh anochi can be rendered in question form as “Why am I the birth site of an unfolding divine story?” And since Torah has no punctuation, it can be read in a declarative exclamatory form: “Why, I am the birth site of an unfolding story!”

Through Rebecca Torah has given us permission to wonder about our own worth, our very reason for existing. It is a question we each carry with us. As we ask it, what was a question becomes a revelation. The Presence that shattered the old and birthed new possibilities at Mount Sinai vibrates within each of us. We are not merely reading a story. We are in it. “I am the birth site of an unfolding story!”

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday November 16 as we explore to be present in the middle of the question.