The pursuit of happiness is found not in the endless chasing after things and experiences to fill our aching souls but in the contentment found in living a life of harmony and connection and reverence. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

On June 1, 1775, Jacob Graff, a well-known Philadelphia bricklayer, purchased a piece of property at the corner of 7th and Market Streets from Edmund and Abigail Physick. He built there a three-and-a-half story brick house. Jacob and Maria Graff and their infant son Frederick moved into their new home in April 1776. The next month the Graffs rented two rooms in their new home, a bedroom and a parlor, to one of Virginia’s five delegates to the Continental Congress: Thomas Jefferson.

Jefferson, tasked by the Continental Congress to write a formal statement of Colonial withdrawal from British sovereign rule, was delighted to find some solitude in the Graff home, which was located on the outskirts of Philadelphia next to a large field. On June 12 the thirty-three year old Jefferson sat down in the parlor at a mahogany traveling desk that he had designed and began to write. Less than three weeks later, on June 28, 1776, Jefferson presented to Congress his draft of the Declaration of Independence.

The second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence includes these words: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

It is that last “unalienable right” that has provoked the most discussion. What did “the pursuit of happiness” mean to Thomas Jefferson, who wrote the phrase, and to his fellow delegates, who embraced it? In a letter to James Monroe in 1786, James Madison noted that “happiness” cannot simply be identified with meeting people’s material interests: “Taking it in its popular sense, as referring to the immediate augmentation of property and wealth, nothing can be more false.”

For Jefferson and his contemporaries, to pursue happiness was the opportunity to live in harmony with the law of nature as it applied to humans. It is a life defined by a moral and spiritual dimension. And, as historian Arthur Schlesinger noted, “pursue” in the context of the Declaration of Independence does not mean chasing after something, but actually practicing it. The pursuit of happiness means living a virtuous life, one that is in ethical and moral harmony with the design of the universe.

This week’s Torah portion, Shoftim, contains two distinct uses of the word “pursue.” One of them refers to a person who is chasing after someone they have accused as responsible for killing their kinsman. The text describes the pursuer as having a “hot heart.” They are caught up in an emotional frenzy. Their loss consumes them, and the heat of their anger drives them in their quest for vengeance and another’s death. Torah intercedes, insisting that cities of refuge be established so that the accused can find sanctuary while the matter is investigated and the pursuer is restrained from unreasonably compounding one death with another.

The second use of the word “pursue” describes a more reasoned and ethical quest: “Justice, justice shall you pursue that you may live and inherit the land that God is giving you.” Like Schlesinger’s commentary on the Declaration of Independence, pursue here means more than chase after. It means to practice justice…continually.

One scriptural use of the word “pursue” describes a state of agitation, an experience of loss, and an explosion of emotion that threatens to wreak havoc on the social order. The other use describes an institution of restraint. Balance needs to be restored where there has been an injury. The heart must be cooled and evidence heard. Such restrained behavior is essential to the creation and maintenance of community. It is a condition for living within the divine promise.

The 1920 census marked the first time in which over 50 per cent of the United States’ population was defined as urban. That shift provoked anxiety and disorientation for many. Representatives elected from rural districts worked to derail any reapportionment process, fearful of losing political power to the cities. It would takes decades, but the pivot from a primarily agrarian country to an urban one would profoundly transform American community, reshaping both national and family life.

The same year as that pivotal census, Edward Hopper, at the age of thirty-seven, had his first one-person exhibition. The Whitney Studio Club, founded by the heiress and arts patron Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, showed sixteen of his paintings. Although nothing was sold from the exhibition, it was a major milestone for him. Hopper would go on to become the most renown American artist to explore the new worlds unleashed by a shifting America.

His paintings, whether scenes of life in the city or of that in the countryside, captured a sense of silence and realignment. Sometimes his settings are vacant of human activity. Railroad tracks, bridges, and deserted gas stations convey a departure awaiting a destination. Paintings that do have humans in them often only have a single pensive figure or two or three individuals who seem not to communicate with one another.

But what prevails most of all in Hopper’s paintings is an elegant restraint. There is a stillness that causes us to spend time with the images in his canvasses. His quiet settings hint at the drama that gives weight and significance to life. Stay as still as the figures on the canvass. Listen to the sounds latent there. His truths are whispered, not shouted. And the more you look, the more you see.

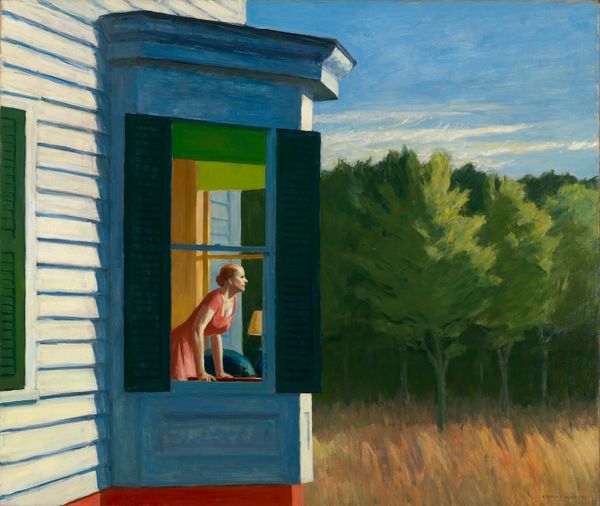

Pictured here is his piece Cape Cod Morning. A woman looks out a bay window at something in the middle distance, something just beyond the frame. The window acts like the prow of a ship, cutting through the sea to a new shore. Is that hopeful expectation on her face, or a longing for a horizon out of reach?

But instead of analyzing her as detached observers and critics, perhaps we should just be with her. We might discover in the elegant restraint with which Hopper has presented her to us what we all need: not the pursuit of things to fill our aching souls but the contentment found in living a life in harmony and connection and reverence.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) on Thursday September 5 as we explore the pursuit of happiness.