Through acts of self-restraint we make make possible a world with others that is called home. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

We are living in a zero sum moment. Ascendant is the notion that one is either a winner or a loser. Compromise is surrender. To tune in to one source of news requires that we tune out another. Library shelves are cleansed. To know the political orientation of one who speaks determines how openly I will listen. The cultural and social voices that tell us what to listen to and what to turn a deaf ear to are deafening.

In such a time, confrontation skills are more valued than those of cooperation. The public arena becomes one of outrage rather than one of consultation and exchange. We breed cynicism and distrust. Stoked are the embers of our anxieties, fears and anger. To survive requires more than defeat of the other. Nothing less than total domination will do.

We have always carried the seeds of such moments within us.One of the earliest stories in the Bible describes a world consisting of a total of four human beings: a man and a woman and their two sons. Yet, one son decides that his own existence requires the elimination of the other. The world is not big enough for both of them. And so Cain becomes the first of us to wander, quivering in constant anxiety, stumbling ever further from contact with wholeness, resolution, peace.

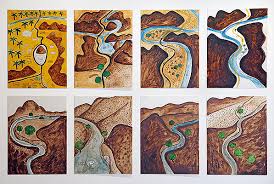

The Israelites in Torah portion Shoftim are at the border between emptiness and fullness, exile and home. Success, victory is at hand. In such a moment Torah promotes not a sense of triumph but one of restraint. It speaks not of the power a king may have, but of the limitations on him: he should not acquire many horses or take many wives or accumulate large amounts of gold and silver.

Cities of refuge are to be set up so that the relative of one who was killed does not pursue the one accused and kill him in the heat of passion. A single witness is insufficient to determine another’s guilt. And justice is a standard to be ever pursued but never perfectly attained. On the cusp of triumph after forty years of wandering, the Israelites are bathed in the cooling waters of humility and self-limitation. That is how to settle in God’s promise.

During the middle of the 20th century, the dominant movement in art was Abstract Expressionism. It was an approach that celebrated muscularity, bold gestures, and thick, broad applications of paint. It called attention not to objects outside of the artist but to stirring, and sometimes turbulent, encounters within the artist.

By the early 1960’s some artists attended to a different, quieter voice. One of those was Agnes Martin. Martin grew up in the wide-open prairies and big skies of Saskatchewan. Having endured a harsh upbringing at the hands of an emotionally severe mother who used silence as a weapon, Martin eventually found her way to New York City and its vibrant art world.

Distinguishing herself from boisterous, fast-paced, attention-demanding Abstract Expressionism, Martin patiently waited for a glimpse of something slight that said it all.

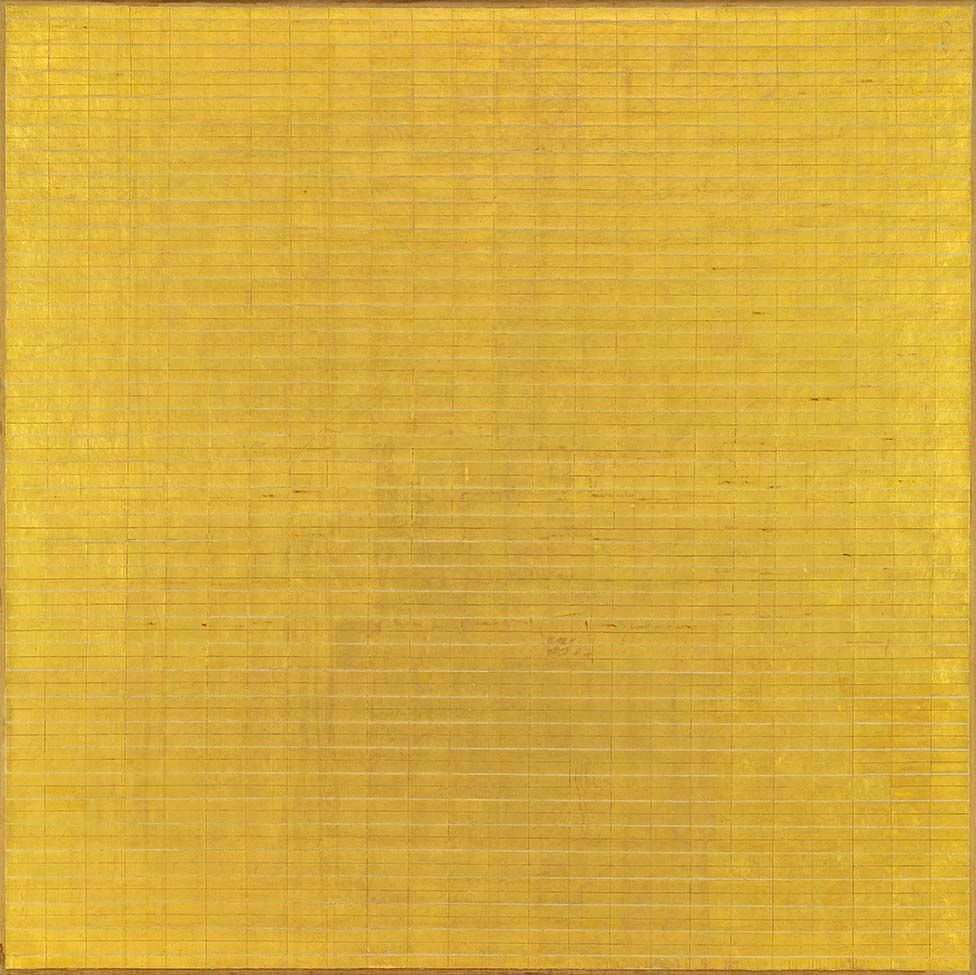

Meticulously, she drew horizontal and vertical lines on large canvasses to which she added color. These restrained, reserved paintings contributed to the development of a new art movement, Minimalism. This new creative expression emphasized simplicity of form in place of the expressive excess of the Abstract Expressionists. Anonymity of creator rather than triumphal self-proclamation.

Presented here is Martin’s painting “Friendship.” Displayed are her hallmark vertical and horizontal lines, which this time are covered in gold leaf. This is not the confessional art of Abstract Expressionism. It modestly holds back. It is a meticulous forming of formlessness. Her works were often attacked, vandalized. Martin understood such reactions to be a fear of emptiness. “You know,” she said sadly, “people just can’t stand that those are all empty squares.”

Martin’s work is infused with the language of Zen and the nullification of our certainty that we know what we think we know. “When you give up on the idea of right and wrong, you don’t get anything,” Martin said. “What you get is rid of everything.”

To grasp and hold, to covet and take is to lose everything. To harden one’s heart, to close one’s ears is not to emerge victorious. It is to become an eternal wanderer, quivering in constant anxiety. By contrast, to paint our lives in restraint is to dwell in the promise of an ever expanding fulfilment that is home.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday August 17 as we explore the expanding power of restraint.