By attending to the mundane we can bring the sacred into the world. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

One of the distinctive features of Judaism is that rather than seeking to lift people to heaven, it seeks to bring heaven down to earth. That is why the primary sacred narrative in Judaism is not about individuals in search of a key to heaven. It is about a people on a journey to settle a land. This is not merely an historical drama. It is also a spiritual one. From its opening chapters the message of Torah is that our mission is to depart both from the perfection of paradise and from the chaos of slavery. We are to take responsibility for building a place that is home.

The primary building tools for this sacred project are very mundane: when to pay someone who does work for you; how to manage a field of grain; how to take care of property that has been entrusted to you; how to loan money and manage debts. Love is the result of this behavior, not the motivation behind it. It is one thing to care for what we love. Judaism’s wisdom is that we love what we care for.

Parshat Sh’lach Lecha tells the story of the people choosing not to enter the promised land. Hasidic tradition reads this as a rejection of the mundane and material tasks of everyday life: farming the land; creating business relationships; building roads; maintaining an army. The people prefer their life lived in the wondrous, close embrace of God. Surrounded by clouds of Glory, eating manna from heaven, drinking water from a miraculous well. They had experienced the Divine radiance at Mount Sinai! Why give all that up for the problems of the world? Hasidic tradition views this critically as a life of “excessive spirituality.”

The Torah portion ends with a new piece of Divine instruction. Everyone is to attach fringes to the corners of their garments. No special, fancy wear. Just their everyday clothing. Something they will see when they look down as they walk, as they herd and farm and work. When done with proper focus and purpose, those are the activities that bring the sacred into the world.

Thousands of years later physicists began to speculate that everything in our universe is made up of tiny vibrating strings. This string theory provided the basis for the theory of a multiverse, the existence of many universes existing parallel with each other. In that context, to reflect on something as simple and mundane as string is to open oneself up to the awe of infinitude.

The African American artist Mildred Thompson was born, in 1936, into a universe of limitations. Though she studied art at both Howard University and the Brooklyn Museum of Art, she could not find in the early 1960’s a commercial art gallery willing to represent her. One art dealer advised her to have a white friend take her work around, pretending to be her. Thompson spent the next twenty-five years living between Europe and the United States. She finally resettled in the United States in 1986 and moved to Atlanta where she taught at Spelman College, Agnes Scott College, and the Atlanta College of Art.

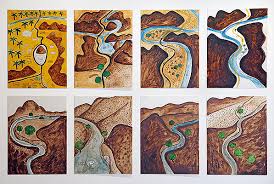

Thompson did not let the universe she was born into constrain her from creating her own. She steeped herself in the study of physics, which sparked in her an exploration of abstract art and its evocative power. She produced a great body of work pulsing with color and movement. One of her series is entitled String Theory. She said that her “work in the visual arts is and always has been, a continuous search for understanding; it is an expression of purpose.” The paintings she birthed in that series both testify to what she discovered in that search and proclaim her power to shape new possibilities.

One of Thompson’s most popular classes was Making the Invisible Visible. Through a simple string on a mundane everyday garment the boundaries of universes can be crossed.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PDT) Thursday June 23 as we explore string theory.