Our power to use language in a way that does not pose final answers but expands questions, mystery and curiosity sustains us through crises and catastrophes.

View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

Translation can be hard. I am in a book group that is reading a novel by the Nobel prize winning Israeli author S. Y. Agnon. In Hebrew the novel’s title is Tmol Shilshom. The English edition we are reading translates the title as Only Yesterday. An older translation renders it as Not Long Ago. A literal reading of the title would be The Day Before Yesterday.

It is a historical novel about Israel, so a sense of time would seem to be important. When did the events take place? Was it a while ago? Just yesterday? Before yesterday?

Or perhaps it doesn’t matter. Maybe for the creative mind there is a conflation of time. Agnon might not have been writing a reproduction of the past. He may have been using elements from the past to express his contemporary experience of Israel. Agnon was, after all, not a historian or journalist. He was an artist.

Agnon was a master of words. I use that term not so much to describe his skill (which was extraordinary) but his role. While a master of martial arts, for example, is highly skilled, more importantly that person serves as the inheritor, guardian and transmitter of a tradition. The great masters are also innovators. They introduce a unique form, kick or punch. Navigating the tension between honoring a tradition and innovating it is one of a master’s greatest skills.

The particular linguistic tradition that Agnon served as a master of was Hebrew. For 2,000 years Hebrew occupied a particular place in Jewish culture. It was the language of prayer and sacred religious text. Literary works, such as poems, that were written in Hebrew were heavily infused with religious references. They were weighted with sacred tradition.

By the end of the 19th century there was a shift in the purpose for which Hebrew was being used: from the fulfillment of religious goals to a secular one, the building of a Jewish state. Those committed to that enterprise reshaped the contours of the Hebrew language: new settings where it would be spoken; an expansion of its subjects; an explosion of its vocabulary; a modulation of the language’s rhythms.

Agnon stood at the crossroads between Hebrew as a conveyance of religious sensibilities and Hebrew as an instrument of mundane everyday transactions. He contributed to the creation of a modern Hebrew literature, even as it became one less facile with references to Biblical and Talmudic tales and more attuned to the exigencies of modern times.

The revival of Hebrew in the 20th century as a spoken language was not a mere reproduction of what once existed 2,000 years ago. It was a reflection of a new context for the Jewish people. And the renewed language reshaped the Jewish people to meet that new context.

René Magritte was a Belgian artist. He was born in 1898, eleven years after S. Y. Agnon. Although he initially identified with the Surrealist movement, he eventually differentiated himself from their flamboyant style, unrecognizable images and forms, and their dark messages. He spent many years working as a commercial artist and embraced the quiet anonymity of a middle-class existence. While Salvador Dali exploded into a room wearing a leopard print jacket and gold-flecked waistcoat, Magritte blended into a crowd dressed in a black suit, white shirt, tie, and bowler hat.

What is disturbing about Magritte’s paintings is not the strangeness of their images. He presents us with easily recognizable figures and objects painted with a commercial artist’s precision and clarity. It is their relationship to our sense of placement, orientation and context.

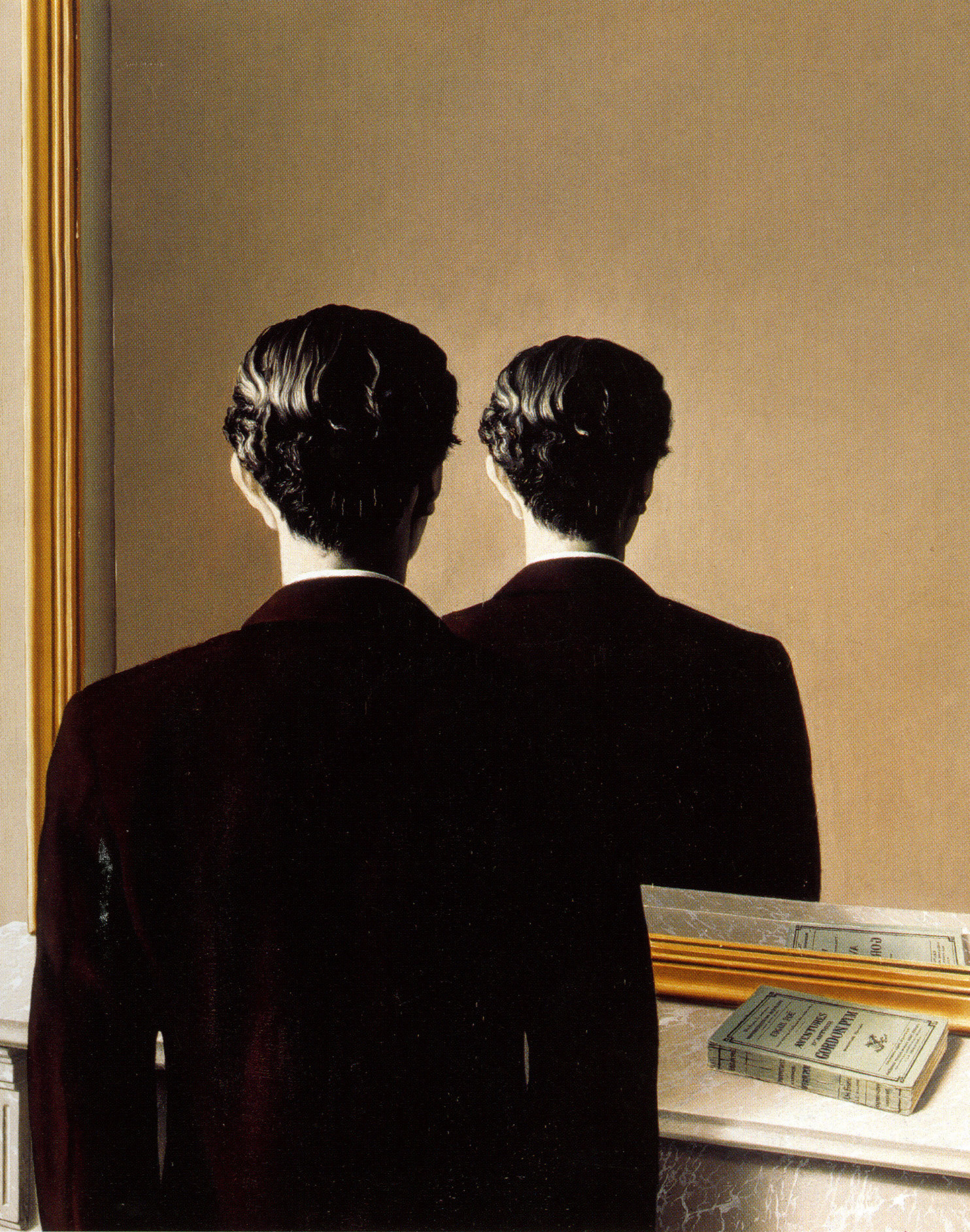

Presented here is his painting Not to be Reproduced. It is a portrait of a man standing in front of a mirror. His hair is precisely described. His suit is tailored but not ostentatious. The collar of a classic white shirt peeks above the jacket. There is no object in the picture that does not seem normal, boring even. Except the mirror bears no reflection of the man’s face. Instead, it carries an image of the man’s back.

What is disturbing is this frustration of our expectation. He has painted a reproduction of what we can easily see, not what we need the mirror to gain access to. What purpose does the mirror play in this painting? And what exactly is “not to be reproduced”?

The mystery, Magritte, suggests, is not that which is beyond comprehension. You do not have to go far or deep to encounter it. Mystery is right before us. It dwells in everyday, mundane detail.

Magritte was also fascinated with the power of language. He incorporated words in many of his paintings, often as instruments to further our disequilibrium as we stand before them. Here he has inserted an entire book in the picture.

The book is The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, a novel by Edgar Allan Poe. It purports to be Pym’s eyewitness account of his journey to the South Pole, a travelogue. That genre of literature became enormously popular in the 19th century, reflecting an increasing curiosity as well as a growing mobility of Europeans.

But something goes off kilter with this straightforward reporting. Pym repeatedly reassures us that he is the real author of the book and not that “Mr. Poe,” who is only the editor of the work. Yet, both Pym the narrator and Poe the editor admit to questions about the truth of Pym’s tale. Everything between the covers becomes a mystery, even though the subject itself is not a mystery but a mere travelogue of an adventure.

Magritte presents to us not a world that we have never seen. It’s a familiar world, just one we have never seen oriented quite this way. Through the use of both image and word we are dislodged from our comfort and invited into a mystery. But it is not one that is beyond our comprehension. With imagination we can see our way through.

Parshat Shemot (“names”) begins straightforwardly enough. It lists the names of Jacob’s sons who traveled down to Egypt with him. Within eight verses something has gone wrong. Pharaoh does not know Joseph, the one who saved Egypt from destruction. Israelite reunion and elevation quickly devolve to enslavement and death. What can provide a new revival for Israel?

A baby is born to an Israelite couple. To protect him from Pharaoh’s decree that all Hebrew male babies be killed, they place him in a teivah. Teivah appears in the Bible in only one other context. God instructs Noah to build a teivah and to go into it in order to avoid the raging waters unleashed as a result of human violence. While in Biblical Hebrew teivah means “chest” or “box,” by the time of the Talmud it also means “word.” Hasidic tradition reads God’s instruction to Noah to mean “go into the word;” that is what will provide sanctuary, meaning and renewed purpose.

Later in Shemot, mystery within a common everyday object becomes the portal for Moses’ initial experience with God: a burning bush that is not consumed. That disequilibrium provokes Moses to ask, “Who am I?” The answer he receives out of the mystery are words of reassurance, “I am with you,” causing Moses to then ask, “Who are you?” The response is not a name, not a noun, but a verbal conjugation: Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh/I will be that I will be. This too is something Moses is familiar with: the verb to be. He uses it every day. But never in such a context, and never in response to a question about identity.

For the Israelite people generally and for Moses personally, a new relationship to language will be their source of self-reconstruction. It will propel them on a journey that will take them across deserts and mountains and rivers, across ages and eons of time. To the nib of Agnon’s pen. To our fingertips dancing across keyboards and to our own mouths bravely giving voice to words of liberation: I will be that I will be.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) on Thursday January 16 as we explore a vessel of meaning.