To see that beyond the apparent fixedness of what is before lies a generative force waiting only to be birthed into new form by our creative work is the gift of a promising spiritual life.

View the study sheet here. Recording here.

Passover, the holiday celebrating the epic story of the Jewish people’s journey from slavery to freedom, concluded just a few days ago. It is a time when we gather around a table with family and friends for a meal and a service of remembering.

The evening begins familiarly enough: lighting candles, blessing children, blessing wine, washing hands, and then….In place of saying a blessing over challah, we break a matzah in half. That breaking of the holiday’s most iconic symbol creates a fissure in the familiar. Children erupt with a series of questions. Those are responded to less by direct answers than by a communal telling of a story, with all of its creative diversions and detours those around the table are inclined to take.

From that moment on the way of children shapes the evening’s discourse. Questions, story and song displace any frontal instruction. Children also control the evening’s conclusion. The seder cannot end until the afikomen is found, until a child brings to the table the hidden half of the broken matzah and restores it to the one held by an adult. The fracturing of the familiar has the curious outcome of reaffirming tradition.

The book of Leviticus introduced itself to us as the most formulaic and least narrative-driven of any of Torah’s books. A manual for the priests on how to conduct a series of prescribed rites, rituals of certainty. Yet, the momentousness of the very first offering is immediately fractured by the horror of two of Aaron’s sons, Nadav and Abihu, being consumed by divine fire for the trespass of impetuously bringing an offering that had not been prescribed.

It is an event that provokes more than a thousand years of questions: Was such punishment justified? Why did the two sons do what they did? Why did Aaron remain silent immediately following the tragedy? A text that opened as a source of detailed clarity and explanation transforms into one of deepest mystery.

Is this text we call Torah primarily one of certainty or doubt; command or question; oration or silence; continuity or fragmentation?

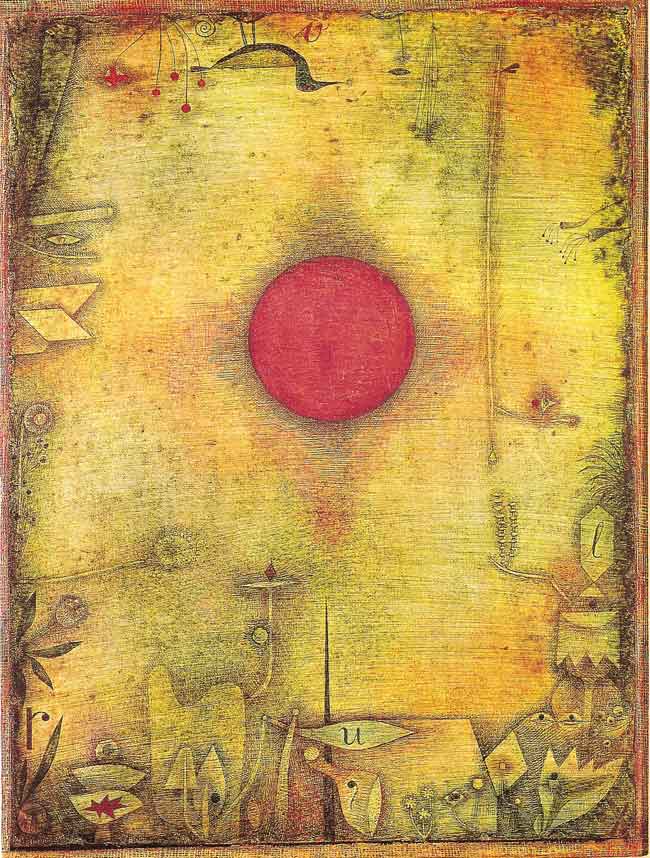

Paul Klee was a Swiss artist who joined with other artists, philosophers and psychoanalytic practitioners at the dawn of the 20th century in dismantling existing structures of certainty and tradition in search of something more primal. In an essay on modern art Klee wrote, “Art does not repeat the visible; it makes visible.” The artist discloses a pulsating, generative dimension that transcends the demands and constraints of time present.

For Klee, the creation of a work of art must be accompanied by a distortion of natural form, “for only therein is nature reborn.” The final forms themselves produced by the artist are “not the real stuff of the process of natural creation.” What is important is the forming itself. To be in touch with that creative process is to become aware that “in its present shape this is not the only possible world.”

Creating fissures in the structures that define established modes of expression and being is the artist’s work. Those openings allow the artist to see infinite possibilities for forms and shapes and colors. What seems to be definitive and final results not from any inherent and limiting trait of the object but from the narrowness of our focus.

Pictured here is Klee’s watercolor Ad Marginem (At the Margin). The perspective is that of a fish looking up from the bottom of a pond. At the margin of the pond are creatures, letters and other symbols. These are the matters of daily life. They are what normally capture our attention. It is where we live. What our egos attend to. We live in the margins of a hugely expansive universe.

The fish has pushed all that to the edges. Its focus is on the sun. The water is still. A calmness pervades the fish’s experience of the pond. The hunting-gathering-self-protection aspects of life have shrunk. The fish is still. Awareness of life’s dynamic, combustive source is at the center of its meditation. The birds and insects and frogs may soon reclaim center frame. But the fish can no longer unknow what it has experienced.

For Klee, the artist is the one who pushes to the margins the press of everyday life. In doing so, the artist realizes that all that one normally sees is in transition. In his essay, Klee expresses his epiphany about where this leads: “The deeper he looks, the more readily he can extend his view from the present to the past, the more deeply he is impressed by the one essential image of creation itself, as Genesis, rather than by the image of nature, the finished product. Then he permits himself the thought that the process of creation can today hardly be complete and he sees the act of world creation stretching from the past to the future. Genesis eternal! ”

In Parshat Shemini two young men create a fissure in the moment of a prescribed ritual designed to be everlasting. They are consumed by the combustive source at the center of their focus. Aaron, their father, the leader of ordained ritual, is without speech. Perhaps the shock and awe of the incendiary moment has disoriented his senses. Puzzled, mystified and horrified, generations of rabbis will rush to fill that opening with explanation, justification and interpretation. Included in those will be praise for the young men and their superabundant love for God.

Maybe Aaron was one of those who could see, see beyond the forms of the moment. Perhaps he saw that in generations to come there would be no animal sacrifices, there would instead be the offerings of our heart. Who is to say that any form can remain everlastingly unchanged? And what is our responsibility in the face of such dynamics? There is, after all, no Hebrew Biblical word for the verb “obey.” The closest is shema. Hear. Attune yourself.

On the Shabbat that the Jewish world was reading Parshat Shemini in 1997, another artist who explored beyond the boundaries of the conventional died. Allen Ginsberg. In his poem “This Is About Death” he had written: Art recalls the memory/of his true existence/to whoever has forgotten/that Being is the one thing/all the universe shouts/Only return of thought to/Its source will complete thought/Only return of activity/To its source will complete/Activity. Listen to that.

Ginsberg saw beyond what has been tamed and brought under control as a noun, a well-defined and static object. He reminds us that the source of all is dynamic, a verb: Being, Activity. That is what “all the universe shouts.” Shema.

Paul Klee reminds us that the world is constantly in the process of creation, of Genesis. Nothing is in final form. Nadav and Abihu loved that aspect of the Divine’s universe, of which they were a part. And every year we gather around a table for poetry and imagination and the fracturing of unquestioned certitude. During that gathering, we ask a child to open the door to the unknown. Can we ask any less of ourselves?

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) on Thursday April 24 as we explore Genesis eternal!