To live in faith is not the same as living with certainty. To live in faith is to live in peace with uncertainty. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

I open the newspaper, I turn on the news, I link to my social media and I encounter everywhere a common complaint: we are so very divided. Yet, it is not division that is the problem. Division is, in fact, a good thing. The Bible tells us that is how everything came into existence, through a separation from an absolute Unity. The Talmud, the rabbinic project that nurtured Jewish continuity during hundreds of years of diaspora, is propelled by argument. On a personal basis, we know how much we grow in both wisdom and empathy from our encounters with those who are very different than us.

The problem is not division. It is the harbor of certitude we retreat into upon encountering a difference. The assumption that one’s point of view is beyond question, that any dissent defines an existential opposition, that any new facts challenging one’s assumptions are not really facts at all is not confined to any one end of the political spectrum. This posture of absolutism and finality about one’s position pervades social discourse today. It reflects an anxiety and a desire to dominate.

For much of history this insistence on hegemony was expressed through the language of religion, where notions of absolute truth settled in easily. In today’s more secular world such notions find their home in political discourse. In either case, the enterprise of absolute certainty serves the purpose of management and control of others: the ability to impose one’s will, to dismiss dissent, and to eliminate difference.

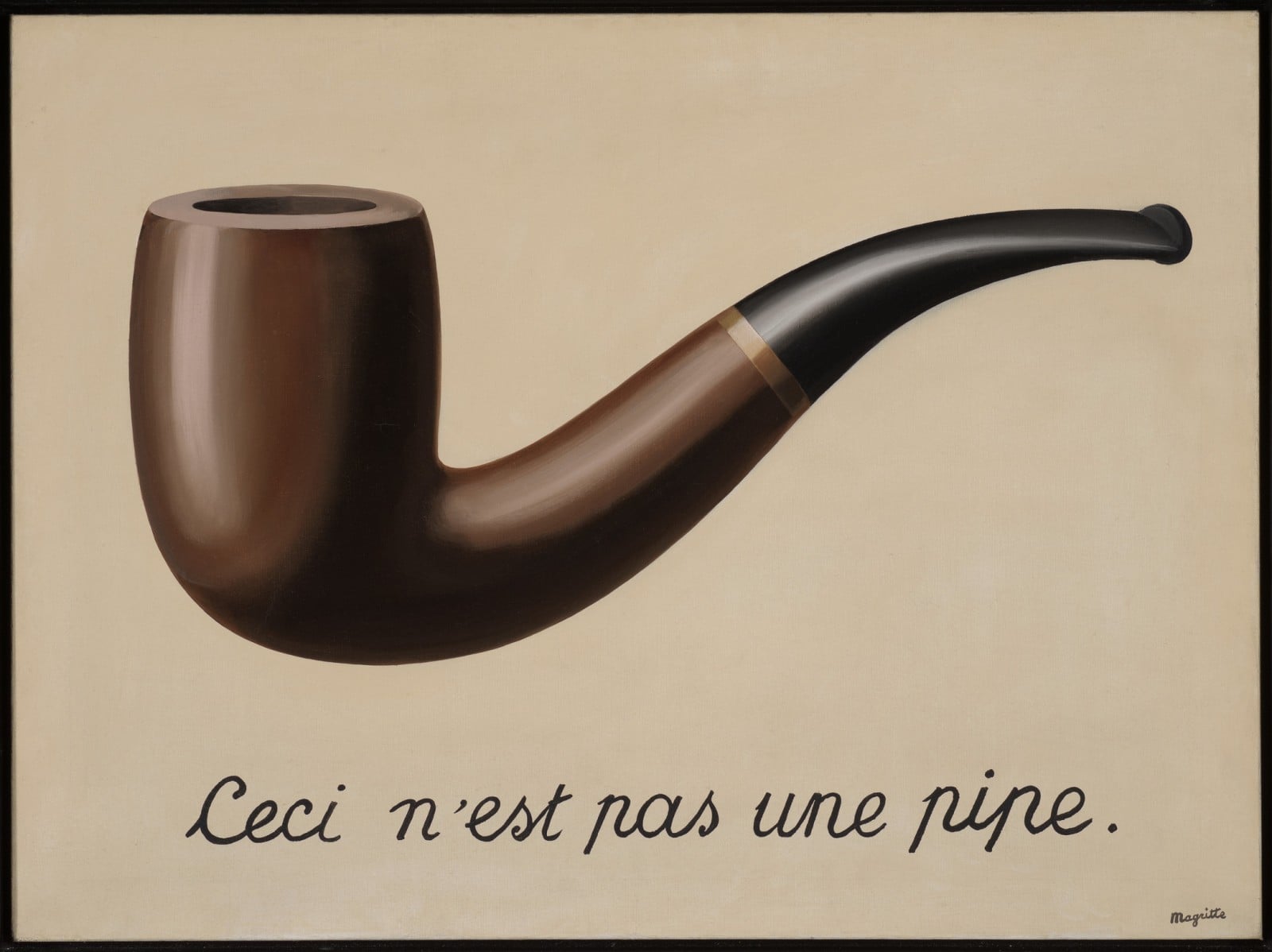

Jewish texts disfavor and deprivilege certitude. The Hebrew language itself relishes in ambiguity. One section of the Bible proudly stands in challenge to the presumptions of another. The entire rabbinic enterprise of midrash is a practice in subverting the apparent and singular reading of sacred text. Meaning is not given intrinsically in the text. It is the product of interpretation, an ongoing, never-ending human exercise.

There is a beauty to this incoherence that induces in us a sense of peace. Because we know that is how life really is: not defined by absolute certainty and coherence but by layers of contending yearnings and by new and unsettling discoveries.

Thirteen chapters devoted to describing the building of the Mishkan have led me to this moment in Parshat Shmini: finally, its inauguration as the vehicle that will bring the community of Israel and God into ongoing communion with one another. This is to be a moment of triumphal connection. And then something goes horribly wrong. The same divine fire that only moments before consumed the first offering strikes out and consumes two of Aaron’s sons. What has happened? Why did a moment of connection instantly become one of horrendous fracture?

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PDT) Thursday March 24 as we explore the art of subversion.