Torah’s mission is not to lift people up to heaven; it is to bring heaven down to earth. The mundane becomes the pathway to the sacred. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

Robert Baden-Powell was a spy. Born in 1857 in London, Baden-Powell joined the British army in 1876. During his thirty-four year military career, Baden-Powell honed special skills as an intelligence officer. Posing as an entomologist, he worked undercover as a spy. He used his cover of studying butterflies as a way to explore enemy positions and fortifications. He transmitted that information to his superiors by drafting elevation contours onto the drawings of the patterns of butterflies’ wings in a book.

During World War I, Baden-Powell published My Adventures as a Spy. In it he described how to create disguises, hide messages, create diversions, and recruit sources of intelligence. With a wink and a nod, he hinted that he had come out of retirement to run spy operations during the early days of the war.

Robert Baden-Powell was also a scout. In fact, he was the founder of the Boy Scouts. While stationed in India, he was dismayed to discover that most of those under his command did not know basic first aid or how to survive in the wilderness. To teach them such basic skills, he wrote a handbook called Aids to Scouting.

After returning to England, he found that his handbook had become quite popular with young boys, who played a game called “scouting” involving tracking and observation. Baden-Powell took a group of boys to the southern coast of England, where, over the course of two weeks, he taught them lessons in camping and survival skills. In 1908 he published Scouting for Boys. By the end of the year over 10,000 boy scouts attended a rally at the Crystal Palace in London. Thus was born the Boy Scout movement.

Spy and scout. Two interrelated yet differentiated roles. A spy is by definition a deceiver, engaged in the theft of secret information. If captured, he or she faces criminal charges and the possibility of execution. A scout, though also engaged in reconnaissance of an opponent’s strength, typically does not discard his or her uniform. If captured, a scout more likely is held to the status of a prisoner of war. A notion of dishonor and suspicion attaches to one who is a spy, even among those on the same side. By contrast, a scout is held in high regard for his or her courage.

The dramatic center of Parshat Shelach Lecha focuses on twelve men who are sent ahead to explore and report back on the conditions and people of the land of Canaan. Some translations refer to them as “spies,” others as “scouts.” Ten of them report that any attempt to possess the land will result in crushing defeat. Are these men cowards, traitors to the divine mission, lacking in faith in God’s promise? Or are they brave advance troops providing a reasonable assessment of what lies ahead?

In a radical reading of the story, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson answers that they were brave leaders of their people. They were not afraid of failure. Quite the opposite. They were afraid of success. Their error was that they misunderstood their mission.

The ten who expressed opposition about proceeding further were, Rabbi Schneerson suggests, pious individuals who wanted to remain in the liminal spiritual dimension of the wilderness. They wanted to remain in the kind of intimate contact with God they had experienced since their departure from Egypt. To enter the promised land meant entering the mundane dimension of daily agricultural tasks, tax collection, infrastructure repair, military and diplomatic alliances. They would be just another nation among many, with the same kind of social, economic and political problems faced by every nation.

They failed to recognize that the mission was not to lift people up to heaven. It was to bring heaven down to earth.

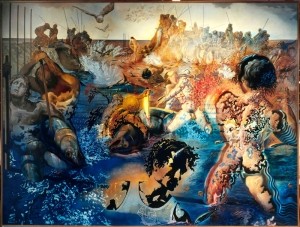

By 1967 Salvador Dali had amassed four decades of profound and provocative artistic work. One of his last great masterpieces was Tuna Fishing. There are two layers to the image. In the foreground are stylized figures such as those one might see in a Renaissance painting. They strain and posture dramatically. In the background are authentic fishermen, less colorful, who go about the work of procuring the day’s food with efficiency and without drama.

In between the two layers, in the middle of the painting, is a figure with head upraised. It is as if he is bringing together the two layers: the mythic and the mundane.

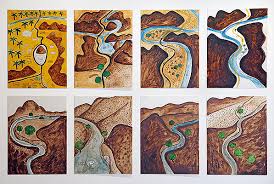

A few months later Dali produced, in response to a commission, twenty-five paintings commemorating the 20th anniversary of the founding of the State of Israel. Pictured in a May 22 post on this page is his painting *Aliyah *from that series. The figure in that painting appears as a reiteration of the central figure in Tuna Fishing. ** **Dali teaches us, by fusing an image representing the fulfillment of the Jewish dream of restored sovereignty with an image of the world of tuna fishing, that the most sacred of purposes are realized through the most mundane of acts.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday June 15 as we explore to make the mundane meaningful.

Oil on canvass Tuna Fishing by Salvador Dali