Imagination liberates us from the grip of what seems to be inevitable, immovable and absolute. With it we can see life and ourselves with new possibilities.

View the study sheet here. Recording here.

During the first two decades of the twentieth century, Albert Einstein conducted research on the force of gravity. This work provided the basis for his theories of relativity. Einstein was motivated to study gravitational force as a result of the failure of the dominant model about the universe, Newtonian physics, to explain recently observed phenomena.

Based on his theories that gravity moved not through a flat, uncurved space as assumed by Newton but through a unified space-time fabric that curved in response to energy, Einstein predicted that light from stars would be deflected near the sun during a total solar eclipse. He offered a challenge: Chart the positions of stars around the sun during totality and then observe those stars in the absence of an eclipse. If his theory of general relativity was correct, there would be a slight difference in the positions of those stars – one invisible to the human eye but detectable through scientific measurement.

In 1919 English astronomers Arthur Eddington and Frank Dyson organized expeditions to the island of Principe off the west coast of Africa and to Sobral, Brazil respectively. During a total solar eclipse on May 29 that year, measurements conducted at both sites confirmed what Einstein had predicted. From that point on stable Newtonian physics was displaced as the sole explanation of how the universe works.

A new field, quantum physics, arose, describing a much more entangled universe, one in which particles can exist in multiple states simultaneously until measured. Perhaps, as some physicists suggest, there is not even a universe… but a multiverse, parallel worlds upon worlds.

Ten years after the 1919 eclipse, Einstein conducted an interview with the Saturday Evening Post in which he discussed his theories and his prediction about that solar event. In the course of it, Einstein said: “I am enough of the artist to draw freely upon my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.” Which of those words jump out at you? “Artist”? “Imagination”? “More important than”? “Knowledge is limited”?

In the context of his work, Einstein was not denigrating knowledge. His theories were based on accumulated observations and calculations. He was emphasizing that the predicted outcome flowing from such work remained “imagined” until scientifically proven. Such imagining was critical to overcoming the dominance of old answers that no longer fully explained our experience of the world.

The innovations unleashed by Einstein and other twentieth century physicists encouraged a new way of understanding scientific progress. Instead of seeing scientific developments as a result of a continuous, linear process, which had been the view since the beginning of the Age of Scientific Revolution in the 16th century, 20th and 21st century philosophers of science have emphasized discontinuities as sites of progress. Anomalies, phenomena unexplained by reigning theories, produce breaks from old models, radical shifts in paradigms and new concepts. Such fundamental changes affect our understanding not only of the world but also of ourselves.

One of those philosophers of science was Gaston Bachelard. Bachelard explored both the world of science and that of literature. In both he focused on the dynamic of building-dissolving-constructing anew structures of observation and explanation. Imagination plays a key role.

In Air and Dreams Bachelard wrote: “We always think of the imagination as the faculty that forms images. On the contrary, it deforms what we perceive; it is, above all, the faculty that frees us from immediate images and changes them.” Imagination serves to deconstruct the seemingly intractable, stable and eternal into material which we can use to design new vessels of meaning. Bachelard describes a process of rejuvenation which does not destroy old frameworks. It melts them into a substance for reshaping. The old is absorbed into the new.

René Magritte was a Belgian artist who shared with Surrealists an interest in the subconscious, dreams and the strange. But unlike their theatrical display of contempt for middle class life, Magritte preferred to present himself as just another 9-5 office worker dressed in white shirt, suit and tie and a bowler hat. His career as a commercial artist distinguished his paintings from those of other Surrealists. Unlike Salvador Dali’s wild and distorted images, those on Magritte’s canvasses are very recognizable and familiar to us: a house, a streetlamp, an umbrella, a pipe. It is just that they appear in contexts that confuse and unsettle us.

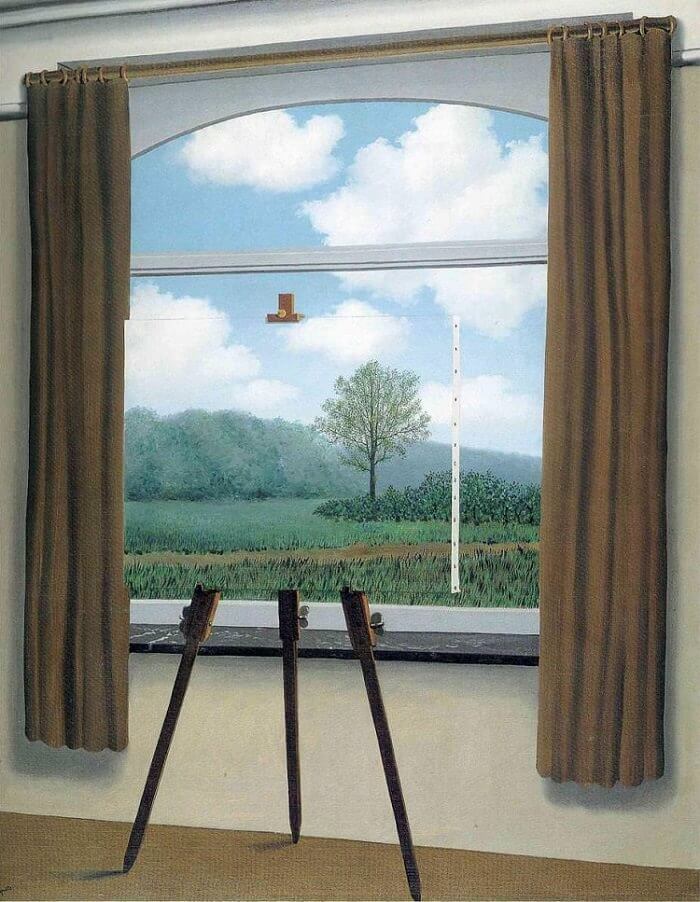

Pictured here is his painting The Human Condition. Every element in it is ordinary and painted with clarity and simplicity: a room, drapes, an easel on which sits a painting, a window, and outdoors a landscape. Our eyes see both on the canvass and in the landscape beyond the window blue sky, clouds, grass, trees, a hill. Our mind creates a continuity between the two images and posits that the scene on the canvass is exactly what lies behind it that our eyes cannot see. But that is mere cognitive laziness on our part. When I showed the painting to my granddaughter and asked her what was behind the canvass, she said: “A circus with a Ferris wheel.”

In a letter to a friend, Magritte wrote: “Everything we see hides another thing. Our gaze always wants to penetrate further so as to see what lies beyond, the reason for our existence.” That extended gaze is effected through our imagination.

In Parshat Pekudei (“accountings”) the Mishkan, the structure designed to enable the Divine Presence to dwell among the Israelites, has been built and erected. The text tells us that when it was finished “a cloud covered the Tent of Meeting and the presence of God filled the Mishkan.” An extraordinary, and perhaps to us an unimaginable, event, but the words themselves are comprehensible. An early rabbinic midrash details the path of the cloud: “the pillar of cloud rose straight up and stretched out over the children of Judah like a sukkah. It covered the tent from inside and filled the Mishkan from outside.”

Wait…”covered the tent from the inside”? and “filled the Mishkan from outside”? Reading those recognizable words in unusual combinations, “cover from the inside” and “fill from the outside,” my sense of physics is disassembled. Newtonian rational certainty is inadequate to explain this bending of the universe.

One way of explaining the phenomenon described by the rabbis in their midrash is offered by Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel: “Meaning is given to those who are mystery-minded, not to those who are literal-minded.” What rational investigation cannot resolve can perhaps find a home in the realm of poetic imagination.

Another early rabbinic midrash explains our Torah text by quoting from Song of Songs, that extended Biblical love poem of intimacy, sensuality and devotion: “His shade (tzel) I desired and I sat in it, and his fruit was sweet to my palate.” This tree, the midrash declares, was one that provided no practical, material shade. It was an intangible, divine element. Yet, it was a shade that satisfied desire and provided comfort and protection. The word tzel is the root of the name of the chief architect of the Mishkan, Bezalel (One In The Shade of God). Bezalel’s primary skill is not material. He is gifted with the wonder and power of letters and words, how to combine them into sources of life and ongoing regeneration.

Just as the Israelites are about to leave the Book of Exodus (Pekudei is its last portion) and enter the realm of Leviticus with its absence of narrative and its details about sacrificial offerings, they are given a lesson about the power of imagination. What seems like a structure of wood beams, metal poles and hide coverings can be turned into a whispered poem about intimacy, devotion and love. And, like the Mishkan itself, it can be packed up and carried with us on our journeys through whatever wilderness we may need to cross to get home.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) on Thursday March 27 as we explore a taste for the imaginative.