We can have both a drive to create, to personalize, to express our individual insights and commit to others in creating a common community. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

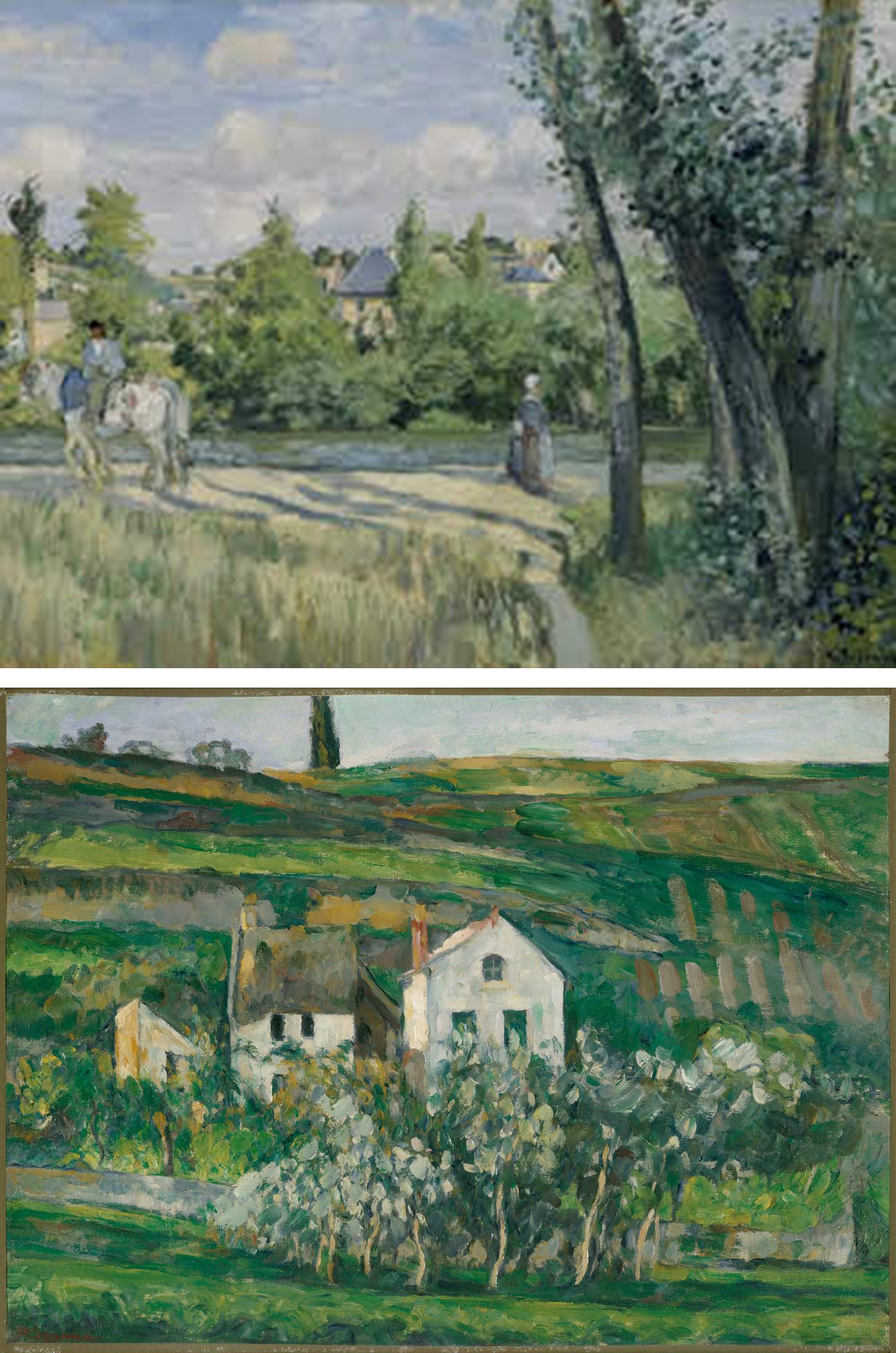

Bottom, Small Houses in Pontoise by Paul Cezanne, 1874

Is conformity a good thing or a bad thing? Humans are social beings. In evolutionary terms, to separate from one’s group could be personally fatal. And for the group, social cohesion was critical for its survival. In modern times new technologies and ways to organize social life have enabled humans to live more independently from groups. The social being is increasingly eclipsed by the individual being.

With that development there has been a shift in sources of authority. Centralized authority – whether in the form of a religious tradition or a secular moral code – has declined in its influence to shape human behavior. Increasingly, the individual has come to see himself or herself as the ultimate arbiter of right and wrong, of what is appropriate and inappropriate.

There has been a backlash to this modernizing of social life. Throughout the Western world in particular, a growing number have asserted the value of such institutions as religion and family in contributing to greater social cohesion and transmission of social values, norms and purpose. And in Europe there is an emergent movement reasserting the value of national identity that is challenging a generational experiment of displacing that with a continental identity.

Despite the trends of modernity, on a personal level conformity continues to play an ongoing motivating force. We learn social skills at an early age by observing and copying the behavior of others. Even in this modern age of individual autonomy, we observe and adjust how we dress, communicate and conduct ourselves based on what we see around us. We want to be accepted, to be part of the group.

Negatively, conformity can involve coercion, a suppression of innovative ideas and excessive polarization. It can lead to mistrust, and even violence, towards those deemed to be outside the group.

Torah is full of messages promoting the value of group cohesion and identity. More than that, it offers warning after warning about the consequences of violating communal standards: stoning, being swallowed up by the earth, and getting cut off from the group and left to wander.

All of this makes sense in the historical context of the story. To wander across the ancient wilderness was a harsh condition. Survival apart from the group was unimaginable. Family. Tribe. Nation. These were not mere accessories to one’s identity. They were fundamental to one’s existence.

Yet, Torah has a way of weaving into its story threads of counter-narrative. For every message there is a hint of looking at things differently. The story of creation, with its universal outlook, is soon followed by the instruction to Abraham to separate from all that is familiar, from his place of origin. He is to be an Ivri, one who crosses boundaries and starts an entirely new venture.

Such a thread appears in this week’s portion. The book of Numbers begins with a celebration of a counting of the whole Israelite nation. Everyone is arrayed around the unifying structure of the Mishkan. And at the end of this week’s portion every tribe brings exactly the same 35 gifts for the dedication of the Mishkan. Torah recounts the presentation of those gifts in the exact same language twelve times, once for each tribe.

Why the wasted use of precious ink? Is it merely to emphasize conformity, the value of everyone doing exactly the same thing?

Midrash, early rabbinic commentary, explains that while the twelve tribes made identical offerings, each experienced the event through a different lens. To each tribe the gifts symbolized different things, relating to that tribe’s role and unique characteristics and personalities. About these offerings, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson writes: “Even as they relate to the ultimate common denominator of their bond with God, they each bring to the experience the richness of their own creative souls.”

This teaching recalls how the early rabbis understood the experience that is revelation, the moment at Mount Sinai: “And the people saw the sounds…” (Exodus 20:15). Why is “sounds” plural? Each person there experienced it according to their own way. The voice of God became the voices of God.

Camille Pissarro and Paul Cezanne first met in 1861 at an art studio in Paris. Cezanne, nine years younger, admired Pissarro for his courage in rejecting both artistic tradition and training. For his part, Pissarro recognized in Cezanne a genius that was rare. Among all the Impressionists, the two of them became a pair, working and experimenting together for more than twenty years.

In 1872 Pissarro settled in Pontoise, a village north of Paris. Cezanne joined him there the following year. Over a number of years, Pissarro and Cezanne painted and drew side by side. They looked at and produced images of the same settings. Yet, they each experienced something different. And they each painted differently what they had seen together. They used slightly different palettes and different brush strokes.

Pictured here are works each of them did in Pontoise. Pissarro’s painting attends more expansively to the play of light. Unlike Cezanne’s painting, Pissarro’s places human beings in the scene. Pissarro was always engaged with the lives of those around him, especially those who worked in the fields. Cezanne places houses in the foreground. Pissarro has placed them in the background.

Pissarro’s brushstrokes are delicate. Cezanne’s are thicker and more focused on the geometry of what he sees. Already, one can glimpse the early stages of his fascination with the faceted planes that he saw in all objects. An insight that would open the way for the cubism of Picasso and Braque.

Two men sat side by side looking out on a scene. One saw sunlight, the dynamics of light, and the passage through it all of human beings. The other saw the geometry of the fields, the materiality of houses, and the totality of it all bending toward abstraction.

They loved each other, these two men. Towards the end of his life, Cezanne wrote to a friend: “As for old Pissarro, he was a father to me. He was a man to be consulted, rather like God.” About their time spent together, Pissarro remarked: “He became influenced by me at Pontoise and I by him. We were always together, but each of us unquestionably retained the only thing that counts, our own sensation.”

Torah paints its own picture. Of a nation beholding a mountain on fire. There’s smoke and thunder and lightning and trumpets blasting. Everyone realizes they have each experienced it uniquely. And everyone realizes they are each mutually accountable to those around them. This recognition that both personalized experience and communal commitment can simultaneously exist causes a mighty trembling. It is the power that propels a sacred journey.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. on Thursday June 13 as we explore “and all the people saw.”