Every crisis bears within it both brokenness and hope. To act upon the hope within it is a renaissance of imagination, of life itself. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

On April 12, 1959, Senator John F. Kennedy spoke at the national Convocation of the United Negro College Fund. Addressing the challenges facing Black college students during a time of shifting American legal and cultural norms and a period of increasing tension with the Soviet Union, Kennedy observed, “When written in Chinese, the word ‘crisis’ is composed of two characters – one represents danger and one represents opportunity.”

Since that speech the list of public speakers, human potential coaches and organizational development specialists who have repeated that bit of wisdom is long indeed. However, over the past fifteen years a number of linguistic scholars have suggested that one of the Chinese characters composing the word “crisis” does not exactly mean “opportunity” but a less value laden term such as “incipient moment.”

I leave it to Chinese language scholars to clarify the nuance. However, if Senator Kennedy had turned to Hebrew instead, he would have had an excellent model for making the same point about the intersection of danger and opportunity.

Hebrew has three characters that when combined can be vocalized two different ways. The combination of letters שבר can be pronounced as either shever or sever. The first means “brokenness.” It gives birth to the Hebrew word for corn or grain (“that which has been broken into pieces.”) The second vocalization means “hope.” The same symbol evokes both things falling apart and the rising of hope.

It is these composed three characters that Jacob announces in the middle of a famine, telling his sons to go down to Egypt for the שבר that is there. Midrash plays with the tension both in the word and in the moment of Jacob’s life: in Egypt there is both grain/brokenness (shever) and hope (sever). It radically declares that Jacob was not only in the middle of a life-threatening crisis. He also sensed, somehow, that Joseph was not dead, as had been reported to him. But that Joseph was alive. And not only alive but also the ruler of Egypt. Joseph, the shattered fragment of the family, was the source of both food and family restoration.

Jacob manages to see the simultaneity of disaster and renewal. The desperation represented by famine has also given birth to a new possibility. Hope comes into existence only during times of crisis; in a condition of well-being and security, hope is irrelevant. In such moments of inflection, what can make all the difference between disaster and revival is what we choose to emphasize. Jacob embraces the hope released by the fissures threatening to consume his family.

World War I tore the world apart in traumatizing and shattering ways. The number of casualties is staggering: 20 million military and civilian deaths; 21 million soldiers and civilians wounded. It provided a breeding ground for increased suspicion of authority, a sense of the absurd, and a desperate desire, for those privileged enough, to submerse in excesses and indulgences of all kinds. Wandering across the pages of such great writers of the period as Hemingway, Faulkner and Fitzgerald are characters variously lost, with a despairing vision of life, self and nation.

But the crisis of World War I and its aftermath also engendered for some a new hope. More than 380,000 Black Americans served in the United States military during the war. Those who deployed overseas returned home having experienced a new kind of freedom and level of responsibility. Large migrations from the South to the North created very different opportunities. A new spirit of self-determination and pride, social consciousness and commitment to political activism enlivened Black communities.

Strengthening these social and political developments was a rich Black cultural movement, the Harlem Renaissance. Pioneering figures such as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Duke Ellington, and Ma Rainey gave voice and proud presence to an ascendant community. Visual artists too helped shape a new Afrocentric cultural language and palette.

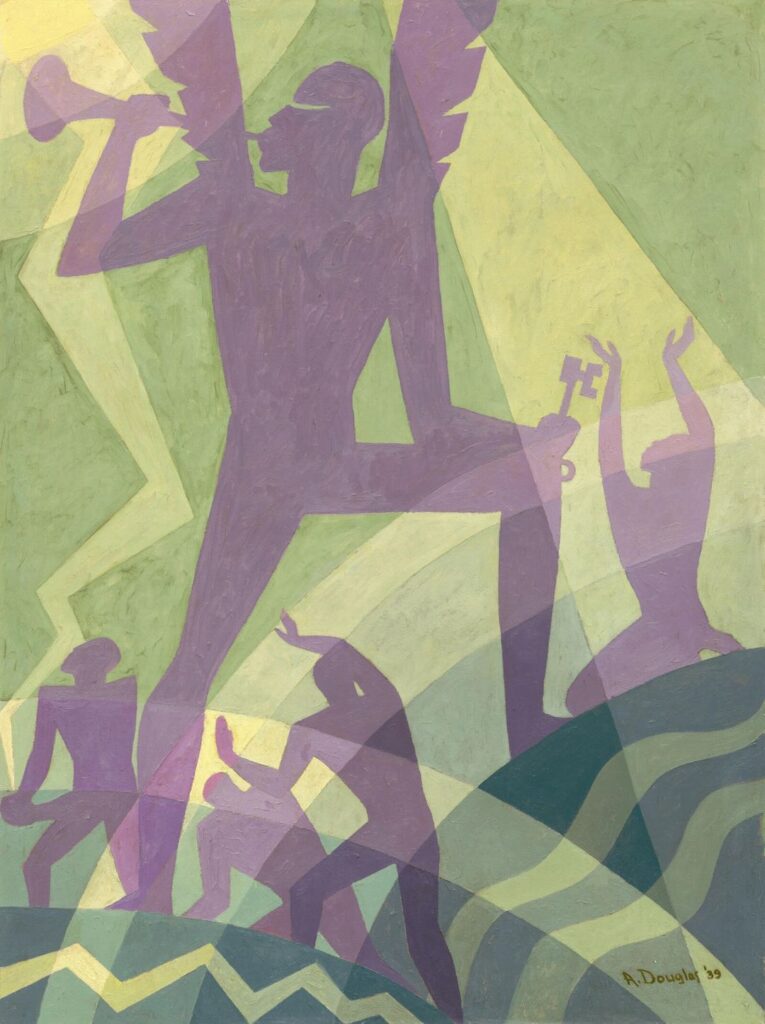

Pictured here is Aaron Douglas’ painting The Judgment Day. Douglas began his artistic career painting landscapes. Influenced by modern art movements such as cubism, which revealed the fragmented and fractured nature of reality, by the modern embrace of bold colors and by ancient Egyptian art works, he began to shape a new aesthetic language in the service of a communal renaissance.

The Judgment Day was originally designed as one of several black and white illustrations for a book written by James Weldon Johnson. Johnson was a lawyer, diplomat, author, and poet. He was also a composer. He wrote the lyrics to “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” known as the Black national anthem. From 1920 to 1930 he served as the head of the NAACP.

In 1927 he published a collection of seven sermon-poems titled God’s Trombones. Each piece was accompanied by an illustration by Douglas. In The Judgment Day archangel Gabriel stands astride hilltops. The circular, wavy and angular lines convey motion. Creation itself seems to be dancing. Gabriel is blowing his horn. In ecstatic and liberated celebration the figures respond in praise and movement. This heavenly messenger, this trumpeter of God’s call announces a new era, one of new possibilities during this time of upheaval and change.

Johnson’s text accompanying Douglas’ illustration includes this poem: And Gabriel’s going to ask him: Lord/How long must I blow it?/And God’s a-going to tell him: Gabriel/Blow it calm and easy/Then putting one foot on the mountain top/And the other in the middle of the sea/Gabriel’s going to stand and blow his horn/To wake the living nations.

World War I unleashed multiple crises. In the middle of them a community responded to the trumpet’s call and created a renaissance. One of its products was the founding in 1944 of the United Negro College Fund, at whose national convocation Senator Kennedy would speak fifteen years later.

His message, whether amplified by Chinese character, Hebrew letters or Harlem Renaissance song “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” awakens us to this truth: every crisis bears within it both brokenness and hope. Every rupture offers a way to reintegration and repair. To see and act upon the hope is the way of imagination and love, to live “calm and easy.”

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday December 14 as we explore the revival of imagination.