Times of crisis, when all seems on the edge, can be navigated by both calling upon wisdom of the past and innovating new approaches for a future just beyond the horizon. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

How do you respond in a time of crisis? Those moments when existence itself seems to be at stake. At such times we might experience a kind of vertigo. Familiar ground becomes unstable. Hearing degrades. We don’t quite understand what others are saying. And words which we once used to create some order in our lives now seem ineffective or, worse, garbled nonsense. Anxiety grows. The edge draws closer. Control seems ever more distant.

At such a moment, do you embrace ever more firmly solutions that worked in the past? Abandon them for ways untested? Or is there some way to do both?

This week’s Torah portion, a double one and the concluding one in the Book of Numbers, Matot-Masei provides an elegant literary framing of discovering new possibilities in familiar settings. Words from each half of the portion revive memories of how the Book of Numbers opened, when all seemed hopeful and orderly. In Matot Moses speaks to the heads of each tribe (mateh). At the very beginning of Numbers God had proclaimed that the Israelites were to be organized according to tribe (mateh). Masei opens with a description of the marches (masei). The first portion in the Book of Numbers told of how the Israelites marched (na’sa’oo, the verb form of the noun masei). This linguistic evocation of the journey’s origins as it draws to a dramatic climax on the edge of the Jordan river is comforting. The past can sustain us into the future.

Yet, there is also a warning in our portion about the dangers of relying too much on past answers in the face of an unknown future. As the tribes assemble to cross the Jordan and claim the territory promised by God in the land of Canaan, two tribes, Reuben and Gad, tell Moses that they will stay on the east side of the river. Moses harshly condemns them for what he interprets as their abandonment of the other tribes in a critical moment in the life of the nation. It is, Moses says, exactly like the betrayal of a promise committed by their ancestors, the scouts, when they refused to enter the promised land thirty-eight years prior.

Generations of commentary criticize Moses for jumping to an incorrect conclusion about the intent and motivation of the two tribes. They may have been less than clear in how they spoke about their intention, but Moses had hastily applied a past episode to a current situation. Just as Moses had inappropriately applied an old way of getting water from a rock in Parshat Chukat and had failed to immediately grasp the new way of transmitting land inheritance as proposed by the daughters of Zelophehad in Parshat Pinchas, here too Moses reverts to old ways at a time when new approaches are required. In Parshat Matot-Masei the future is talking to Moses, but he is hearing the past. There is a grievous miscommunication.

It is great artistry to craft new approaches in a way that honors the past.

Jean Dubuffet was born in Le Havre in 1901. Though attracted to art at an early age, he did not fully dedicate himself to it until his forties. Prior to that he had a successful career as a wine merchant, a business he inherited from his father. After World War II, Dubuffet became the standard bearer of Art Brut (“Raw Art”). He challenged the canons of beauty and order in European art. He traveled to Africa. He visited psychiatric institutions. He looked to the margins of everyday life – the art of prisoners, psychics, the formally uneducated, the institutionalized – as sources of liberation from an oppressive and corrosive present.

He advocated for instinct, passion, mood, even madness as sources of wisdom following a world war launched by strategies, planning and intellectual justification. He also urged closer attention to natural and everyday forms as sources of beauty: “Look at what lies at your feet! A crack in the ground, sparkling gravel, a tuft of grass, some crushed debris offer equally worthy subjects for your applause and admiration.” Dubuffet incorporated these subjects as media in his paintings. He mixed gravel, sand, glass, and tar into his paint. A relentless innovator, he made impressions from foliage, orange peels and tapioca.

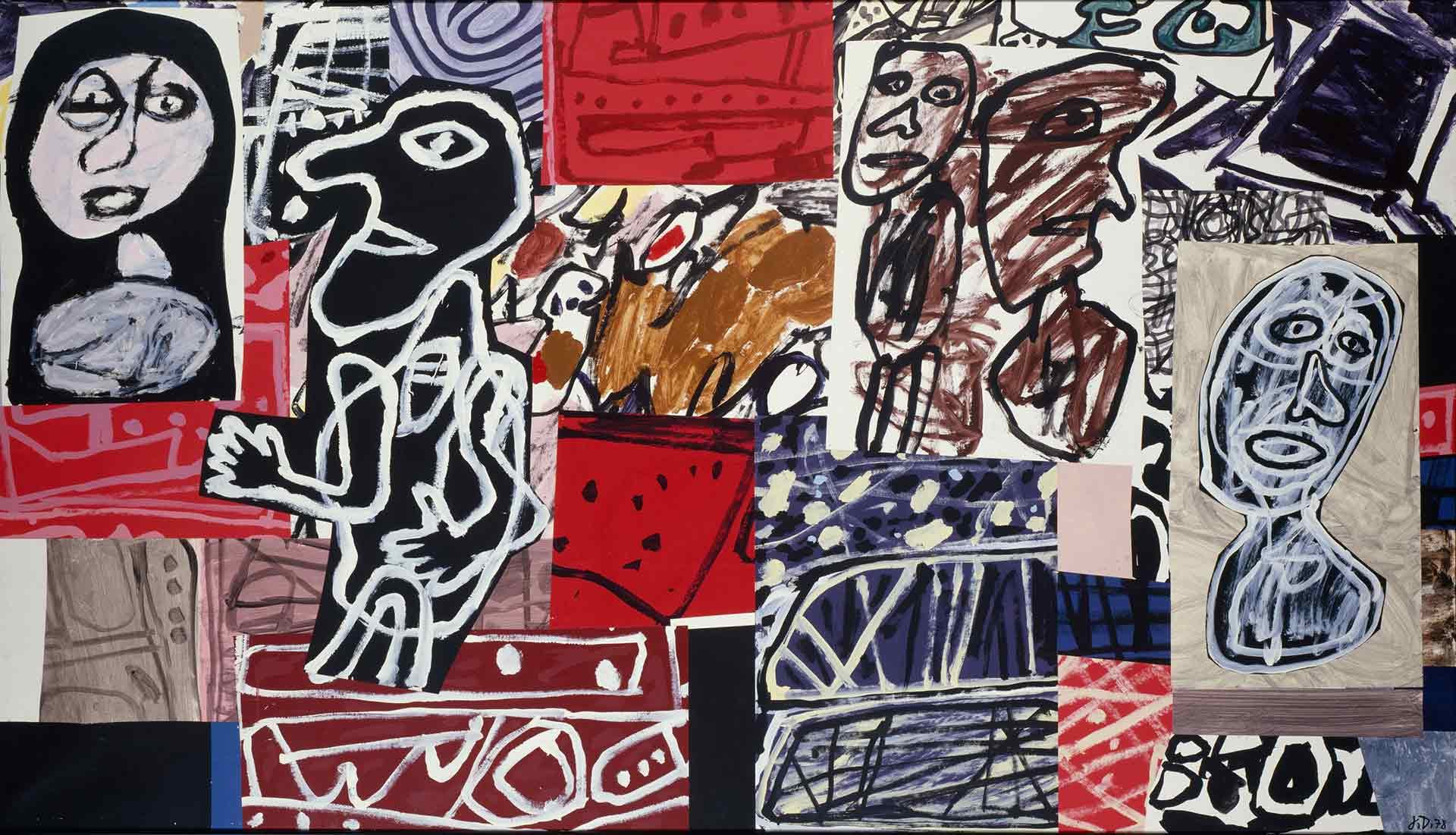

In The Misunderstanding, painted in 1978, there is a mixture of the primitive and the modern. There are faces, but they are turned in every direction except toward one another. For Dubuffet, this is the anguish of our times. A seemingly sane world that could not look at itself enough to restrain from killing 50 million + of its own. Better to abandon the pretensions of civility with its underlayment of violence and embrace the strange and unconventional: “What is picturesque disturbs me. It is where the picturesque is absent that I am in a state of constant amazement.”

Yet, Dubuffet also understood the dangers of a complete erasure of the normative, the recognizable: “I want my street to be crazy…and that is why I deform and distort their outlines and colors. However, I always come up against the same difficulty, that if all the elements were one by one deformed and distorted excessively, if in the end nothing remained of their real outlines, I would have totally effaced the location that I intended to suggest, that I wished to transform.”

If the artist Dubuffet struggled to find some accommodation between the strange and the familiar, the poet T. S. Eliot in his poem “Little Gidding” finds some way for their co-existence. Like Dubuffet’s work, Eliot’s poem has as its background the death and destruction caused by World War II, in particular the German aerial bombings of England. He plays with the image of fire as a source of both destruction and purgation and renewal. It is a contemplation of endings and beginnings. Ultimately, it is a poem about tradition in the present and a present-day poem that absorbs past traditions. Like Parshat Matot-Masei it takes us forward to the beginning, which is perhaps how to best face the inevitable crises in our lives:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PDT) Thursday July 28 as we explore art at the edge.