We walk through a life often far more foggy than we would like. The responsibility to determine what is true requires reflection, integrity and above all a sense of justice. View the study sheet here.

“We are a nation divided…” It has become almost obligatory to insert those words into contemporary articles about our political, social and cultural life. How frequently that phrase is used almost dulls our awareness of how precipitous is the destruction it warns us of. Increasingly our news is broadcast from siloed cells of passionate partisanship. As the social fabric around us unravels, we hold tightly onto whatever thread of certainty is within our grasp.

Jewish tradition has viewed division not as a source of destruction but as one of creation. The profusion of life forms described in the opening of Genesis is meant to point us back to their single Source. Our mission as human beings is not to look past our differences in order to see our common origin. It is to look attentively upon them and behold there our sacred unity.

The Talmudic enterprise is driven by the engine of argument. The rabbinic term for argument, machloket, is derived from the Hebrew root which means both to divide and to share. The rabbis argued with one another not to vanquish one another as opponents but to work together collaboratively as partners in order to open up space for the birth of new perspectives, for the generation of innovative approaches to the challenges of everyday life.

What then to do with the picture in this week’s Torah portion of the fierce argument that erupts into a rebellion against Moses and Aaron? One which results in some rebels being swallowed by the earth, and others being killed by fire or by plague.

Over generations readers studied this picture and found surfacing in it hues not of contempt but of love for the mission of creating a community in which the divine might dwell. The 19th century commentator Ha-amek Davar wrote that the fire pans of the rebelling Levites were turned into a covering for the altar because they were not really rebels and sinners but people who “longed to do the will of and get closer to God.”

Rav Kook, the early 20th century kabbalist and chief rabbi in pre-state Israel, emphasized the constructive role played by critics of the status quo: “The holiness of the fire pans symbolizes the necessary role played by skeptics and agnostics in keeping religion honest and healthy. Challenges to tradition are necessary because they stand as perpetual reminders that religion can sink into corruption and complacency. Plating the altar with the fire pans of the rebels reminds us of the holy impulse within each of us to rebel against religious stagnation that can infect religion.”

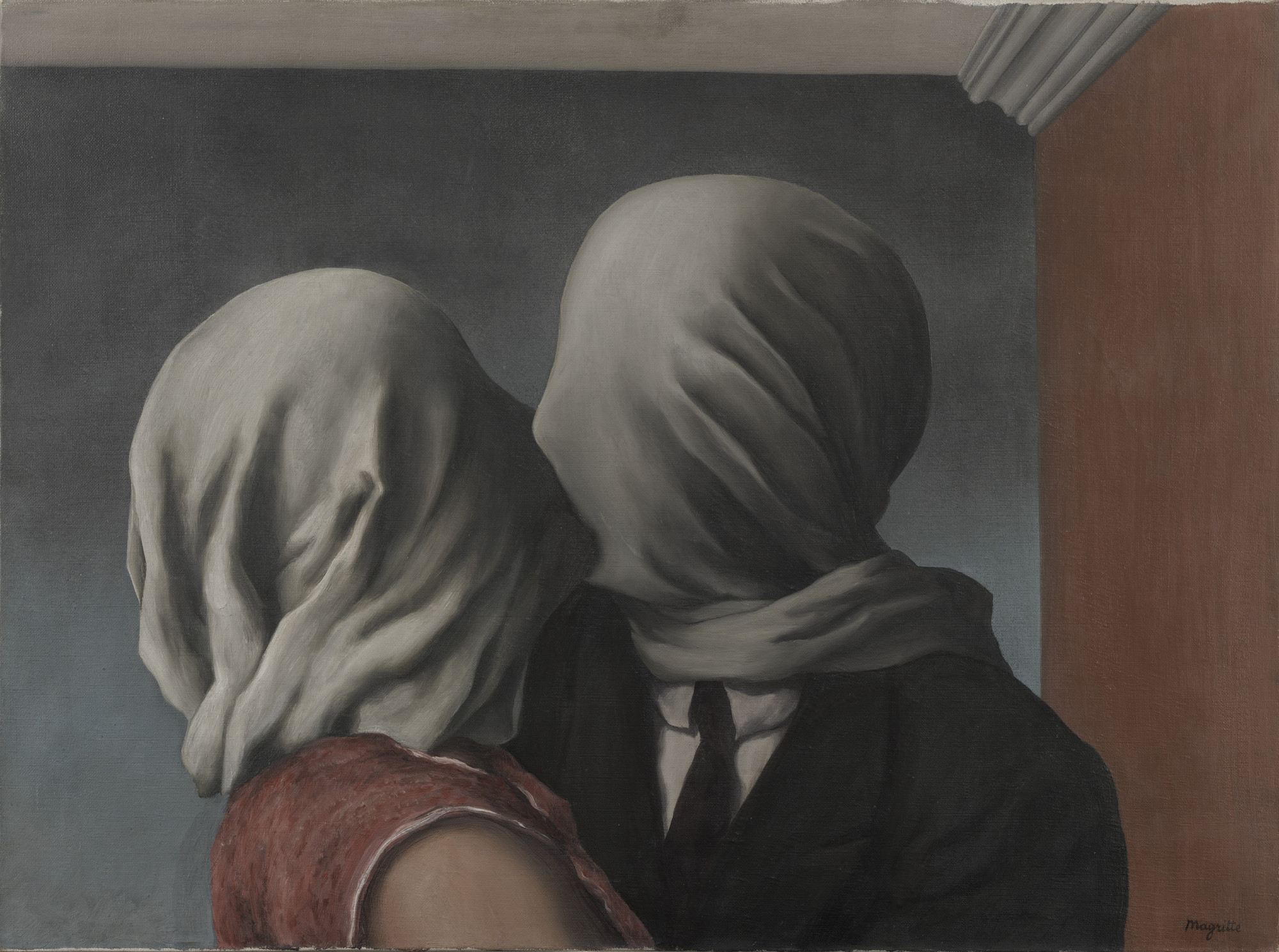

Rene Magritte shared the Surrealist contempt that centuries of enlightenment, with its emphasis on reason and science, had culminated in the horror that was World War I. The Surrealists particularly poked at the developing middle class, the prime beneficiaries of the liberation of the individual from ancient, feudal constraints. By the late 20th century more social commentators observed that the rise of the autonomous individual had come at the expense of a fraying of social connection.

Pictured here is Magritte’s painting The Lovers. Two individuals embrace. Their faces are each wrapped in cloth. The small space they inhabit has no windows to provide any perspective. The barrier of the fabric prevents intimate contact. Their inability to see one another, their lack of connection to a world beyond their walls transform an act of passion into one of isolation and frustrated desire. There are lovers. But where is the love?

The rabbis of the Talmud understood that love is not merely an emotion. It is more importantly a discipline. One that requires work and attention: “In a war between two sages, they did not move from there until they became lovers” (Kiddushin 30b). A contemporary Hasidic rabbi, Rav Itamar Eldar, comments: “The love the Sages promise is not the resolution of the dispute, but rather the ability to contain both sides of the uncertainty.”

Uncertainty is risky and frightening to embrace. To see one another, to listen to the other, to look upon others with a sense that they possess an understanding of truth that we have overlooked requires courage. And that is where love is found.

Join us as we explore where is the love.