Beginning with a respect for diversity is likely to lead to an awareness of unity; while an insistence that all is unified is likely to lead to destructive division. Watch the recording here.

Public debate in our country today occurs at an incendiary level. Every argument seems to have hovering over it a menacing violence. Whether the topic is guns, women’s health, elections, or even public health guidelines, there is a tension that disagreement could quickly devolve into physical mayhem. It is enough to make me want to avoid the public square and perhaps surrender that territory to those better armored, or armed, than me. What a tragic state for this great experiment in democracy to have fallen to.

Judaism is not without images of violence erupting out of differences of opinion. In this week’s Torah portion two groups rise up to challenge the political and religious authorities in the Israelite community. Members of the tribe of Levi confront Moses and Aaron, challenging especially Aaron’s role as exclusive religious leader. After all, they argue, at Sinai God had announced that all of Israel was “a kingdom of priests.” And members of the tribe of Reuben contend with Moses over his entitlement to lead the nation. After all, they are descendants of Jacob’s first-born. They should hold political leadership over the family of Israel.

The Torah then describes a horror of fire, plague and a burying alive that consumes those who had challenged Moses and Aaron. Barely do the shrieks of those devoured by the earth fade before the two brothers move to re-assert their claim of authority through a ritual of elevating Aaron’s staff above all those of the other tribes. The text seems to clearly condemn as heretical rebels Korach and his co-conspirators. This would seem to set the stage for what would happen to anyone who challenged established authority or opinion: death and destruction.

However, the rabbis of the Talmud were determined to expand rather than narrow the field for disagreement. Debate among the sages certainly becomes a form of combat. Yet, in that system, argument becomes not a threat to stability. It is a source of new understandings. Of life itself. The very word used for argument machloket means both to divide and to share. Distinctions are made, lines are drawn so that a bigger picture can emerge.

The Talmud tells us that “in a war between two sages, they do not move from there until they become lovers.” The love the Talmud promises is not the resolution of the dispute but the ability to contain both sides of the uncertainty. To see more than they had before.

Prior to the Impressionists the range of what was deemed an appropriate subject for artists was rather limited. Only those who painted moralizing scenes from history or mythology or which glorified the established order could gain patronage and exhibition of their work. The Impressionists directly challenged what was acceptable subject matter, where to paint, technique, and how art was sold. And they expanded admission into the ranks of artists.

Until the Impressionists women were virtually unable to obtain a formal art education. The École des Beaux-Arts, founded in Paris in 1648, served as the gatekeeper into the world of art inFrance. It did not even begin accepting women until 1897. The community of Impressionists was a different world. When the Impressionists began to exhibit, their art was criticized as being “feminine.” Instead of grand, moralizing images, the Impressionists depicted everyday life. A scene of a picnic in a park defied the standard of gravity traditional art required.

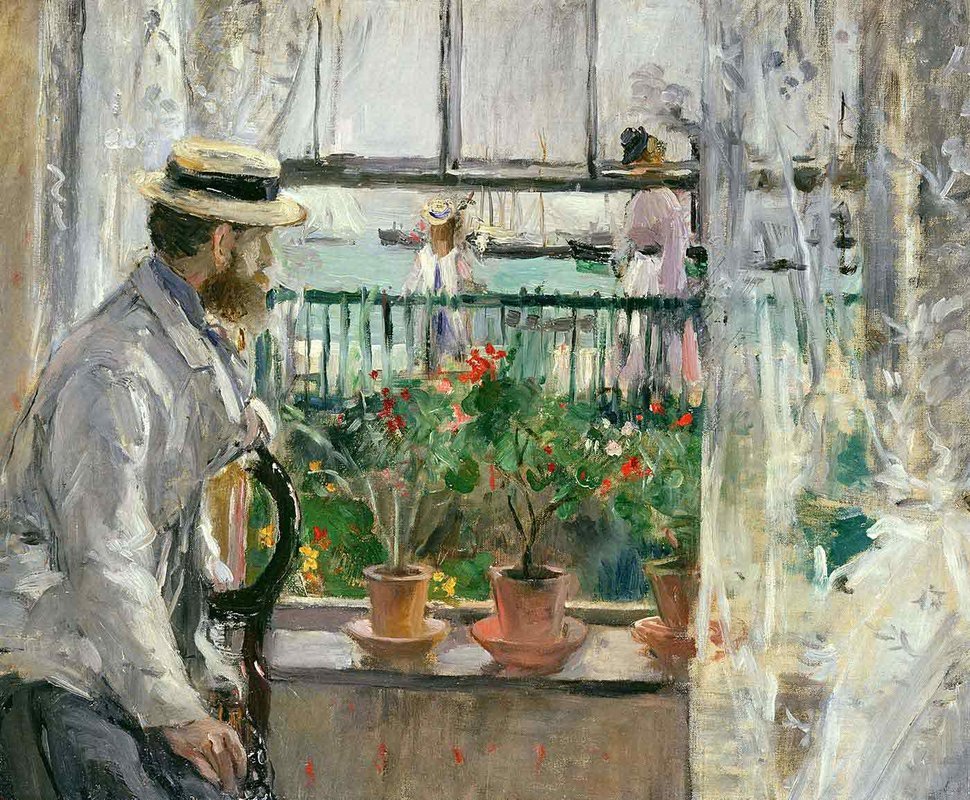

Berthe Morisot, born in 1841, showed her work at the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874 and went on to participate in all but one of the eight exhibitions between 1874 and 1886. In 1875 she painted In England while she and her husband Eugene were on a honeymoon there. Notice how many frames there are. The window through which Eugene gazes is one. Each pane forms an additional frame. The window is half lowered, creating a separate frame with the fence outside. The slats in the fence give shape to a series of vertical frames.

Consider the points of view she presents to us. Eugene is holding a pair of binoculars. He had been looking at something, perhaps the boats in the distance. Now he is looking at the woman outside. The woman is looking at a young girl. She, in turn, is gazing out to sea. There is a fourth perspective. The painter, the female painter, Morisot. She is sharing with us her perception of multiple perceptions. Many different ones happening at a single moment. And she has given each of us an opportunity to have our own as well. Perhaps you will focus on the three flower pots on the window ledge. Or on the colorful garden. Maybe on a third look you’ll be drawn to the curtain in the foreground. Is that a tear in the material?

Morisot focusing on the mundane – a man, a window, a woman, a girl, the sea, boats – provides us with what is truly profound: we each see different things in a moment we all share. And she doesn’t narrow our attention or insist that one of those perspectives must prevail. She just offers us a bigger picture.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PDT) Thursday June 30 as we explore seeing the whole picture.