The origin of our redemption lies not in an intervention from outside of our nature but in a stirring from within it. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

Could changes in color choice, composition and subject matter on a canvass accelerate shifts in social power? Can a difference in brushstroke subvert an elite’s hold on what is deemed true and everlasting? Does an artist’s hand have the power to unshackle centuries of domination by those of inherited wealth and position over those of meager means and limited political influence?

On April 15, 1874, the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers, etc. opened an exhibition at the Parisian studio of the photographer Nadar on the Boulevard des Capucines. That opening directly challenged the government’s control over the public exhibition of art. Those “anonymous” artists, eventually known as Impressionists, also dared to reject classical art’s focus on religious, historical and mythological themes in favor of everyday life. Their small, short brushstrokes, attention to light and movement accentuated the immediate and transient sense of time versus classical art’s emphasis on the eternal and ideal.

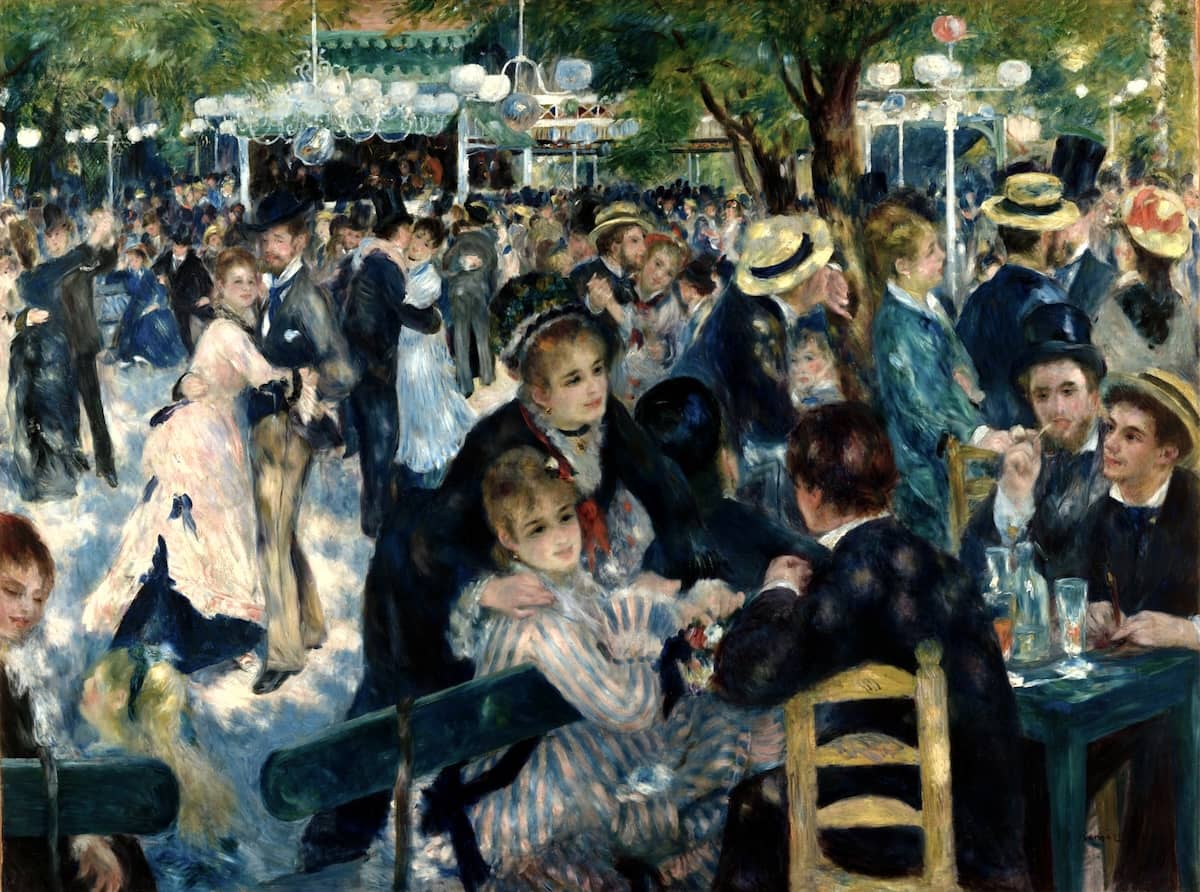

Pictured here is Renoir’s Bal du moulin de la Galette, painted in 1876. Le Moulin de la Galette was located in the Paris district of Montmartre. Montmartre was far from the kind of location idealized by classical art. It was the site of the revolutionary uprising the Paris Commune in 1871. Le Moulin de la Galette itself was a dance hall, where artists and working class Parisians would go to party, socialize and dance. Renoir has pictured them here on a Sunday afternoon. Instead of the precision and clarity insisted by classical art, Renoir blurs the scene, using a loose brushwork and a vivid color palette. As a whole, the painting stands as an overthrow of aristocracy, traditional authority, and the permanence of the past. It celebrates common people, everyday life, including its pleasures, and the ephemeral nature of time.

The Impressionists’ insistence on individual perception challenged contemporary controlling notions of reality and gave permission to generations of artists to pursue their own visions. The Impressionists’ elevation of evolving, transitory everyday life celebrated the power of every human being to contribute to the world’s beauty.

After the scene of the giving of the Ten Commandments, the Torah surprisingly paints for us in Parshat Ki Tisa a vista that encourages an assertion of human initiative, even in the face of divine proclamation. Up on Mount Sinai, God instructs Moses to “raise up” the faces of the Israelite people. During Moses’ absence, the people insist that Aaron “make a god to go before them.” Did they not see that the covenant they had just entered into required an elevation of their human responsibility and not the manufacture of another all-powerful being, such as those they had witnessed in Egypt, to merely follow?

Upon seeing this moral failure, Moses smashes the tablets he had received. After expressing sorrow and seeking forgiveness on behalf of the people, Moses returns to the top of the mountain for a second set of tablets. This time, however, there is a radical change in their design. Instead of being inscribed by God, the words upon them are written by Moses. The portion ends with Moses’ face in a radiant glow. At first the people are frightened, but eventually they draw near to their leader who has modeled this most radical assertion of human initiative.

The early twentieth century kabbalist and chief rabbi of pre-state Israel Rav Kook distinguished between the redemption experienced by Hebrew slaves from Egypt and that which is ever needed in the future. The former required a supernatural intervention, a “Divine rescue from above, an awakening from above.” But a future redemption, he wrote, “will take place within the laws of nature. It will emanate from the stirring of the human heart. It will be an awakening from below.”

Renoir and his compatriots painted a vibrant vista of human beings liberated from constraints of the past so that their unique insights might flourish. Torah has painted for us a challenging and ennobling image of what it means to be a human being: to raise ourselves up to new levels of moral responsibility and mutual accountability. To live in accordance with Torah’s image of us is to live with raised up and radiant faces.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) on Thursday February 29 as we explore an awakening from below.