When we go out from the fears and anxieties and narrow visions that constrain our souls, we can experience the promise of a life of peace and fulfillment. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

At the age of eighteen, a restless young Parisian artist, Théodore Rousseau, traveled outside the borders of Paris in search of a location that could provide the kind of inspiration that he could not find in his teacher’s studio. He came upon the vast and untamed Forest of Fontainebleau. Reaching nearly 42,000 acres, the forest consists of dense woods, marshes, vast meadows, imposing rock formations and breathtaking vistas. Rousseau had found his inspiration.

Rousseau would return there over the decades to sit in stillness in the presence of nature. In reverence he would receive what the forest presented to him: a stag rubbing its antlers; the elegant display of lilies; a cathedral of trees. He honored those gifts by painting outdoors in their presence these images and the sensations they evoked from him: “There is composition when the objects depicted are not depicted for themselves but for the purpose of continuing, under a natural appearance, the echoes they have placed in our soul.”

With the paintings that Rousseau created, he, and other artists who ventured with him into the Forest of Fontainebleau, launched an assault on a system that had controlled art for over a thousand years: what artists painted; how they painted; and where they painted.

Prior to the 19th century, art was a highly closed system. In more ways than one. Artists did not choose their own subjects. They were commissioned by patrons to create specific works. Throughout the Middle Ages the Catholic Church was the primary patron of the arts. It commissioned works designed to inspire devotion and to promote religious doctrine. During the Renaissance, wealthy families commissioned artists to create pieces that would promote their wealth, power, and cultural influence.

Subject matter was limited primarily to religious narratives, classical mythology or important historical events, themes that re-enforced the social hierarchy and power of religious, royal and wealthy private patrons. Established in the 17th and 18th centuries respectively, officially sanctioned art academies in France and England enforced both subject matter and style standards. Artists who painted outside those standards were refused exhibition of their works.

The work environment of artists reflected this closed system. Artists in the Middle Ages worked in monasteries and other religious institutions. During the Renaissance, they relied upon their patrons to provide them with workrooms and studios. The academy system maintained a network of officially sanctioned studios which ensured adherence to approved subject matter and aesthetics. In all cases, painters did their work inside. Nature was not a valued subject. It served primarily as backdrop for a message of moral or historical importance.

In defiance of those conventions and restrictions, Rousseau and his colleagues painted in open air scenes of nature which inspired a new generation of artists, who would become known as Impressionists. Among that new generation was Claude Monet. In painting scenes while outdoors, Monet took Rousseau’s instruction to depict “the echoes they have placed in our soul” to an entirely new dimension. Increasingly, Monet displaced naturalistic depictions of objects by infusing the canvass with his subjective response to them.

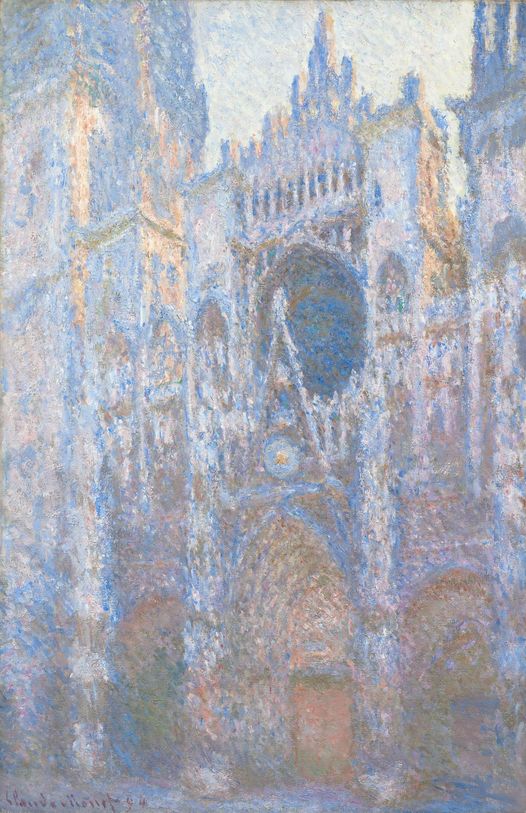

Pictured here is his painting Rouen Cathedral, West Façade. Monet did more than thirty views of the cathedral, sitting before it at different times of day to experience its transformation with the shifting light.

Rouen Cathedral was begun in 1030. It was completed in 1506. More than 800 years would pass from the laying of its foundation to the day Monet sat before it with his easel, brushes and paints. A towering structure, it conveys what its builders over the centuries had intended: substantiality and eternality. Through the diffusion of its form and the use of unusual colors, Monet shows us other dimensions in the cathedral’s life: insubstantiality and impermanence. He reveals the cathedral as both immovable and fleeting.

Monet and his fellow Impressionists did more than defy convention about how an object could appear on a canvass. They were the first to hold independent exhibitions; their movement inspired the development of galleries; and they impacted how art would be marketed and sold. All of these innovations, which freed artists from ancient constraints, began with going outside to paint.

For Monet, going outside was about more than where one painted. It was about unleashing the soul in its unique creativity: “When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have before you, a tree, a house, a field or whatever. Merely think here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you.”

The title of this week’s Torah portion, drawn from its first two words, is “When You Go Out” (Ki Teitzei). It contains more instructions than any other portion, all addressed to Israelites packed up and ready to go out from the wilderness and into the realm of divine promise. The phrase “going out” is repeated later in the portion: “Remember what Amalek did to you on your way of going out from Egypt.”

The “going out from Egypt” (yetziat mitzrayim) becomes in Jewish tradition the term for the entire forty year journey, the travel from slavery to freedom. Transmitting the story of that journey is a prime directive for parents and is the reason for having a Passover seder: “You shall tell your children: It is because of what God did for me in my going out from Egypt” (Exodus 13:8). Note that we are instructed to declare ourselves as having been on that journey personally.

Yetziat mitzrayim refers to more than a historical event that occurred once, thousands of years ago. It is the endeavor to rise above all that inhibits the soul, whether imposed by an outside force or by physical, psychological or spiritual limitations arising from within ourselves. We are, all of us, constantly on the verge of entering into the realm of divine promise. And all of us have been touched by a power that calls us to a responsibility for one another. When we go out from our fears and our separations, we create art that is transformative.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) on Thursday September 12 as we explore when you go out.