The sacred instruction to remember is a call to participate in a journey to freedom and responsibility that was started long ago. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

What happens when we see the world differently than others do? In 1876 a group of artists who had been excluded from the officially sanctioned art exhibition in France known as the Paris Salon decided to hold their own. The group included Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas. Founders of the Impressionist movement.

Their paintings challenged more than the reigning aesthetics of the day. They also challenged the very notion of how we perceive reality, and what is the reality we perceive. The expansion of experimental science in the 16th and 17th centuries gave rise to the notion that true knowledge comes from our sensory experiences, from observation. This formed the basis of empiricism, which proposes that there is an objective reality to be known.

The Impressionist painters rejected that view. They held that we don’t really see the natural world objectively because everything we perceive is filtered through our unique and personal memories and emotions. Each of our minds perceives the world differently. The Impressionists sought to visually represent not the object but their experience of perceiving the object.

Critics of the Impressionists considered them to be insane. Responding to a painting Pissarro displayed at the 1876 exhibition, the art critic Albert Wolff wrote: “Try to make Monsieur Pissarro understand that trees are not violet, that the sky is not the color of fresh butter, and that no sensible human being could countenance such aberrations.”

The public took to calling the gallery where the Impressionists exhibited a “hall of lunatics.” Wolff wrote that what he had witnessed at the exhibition was the “frightful spectacle of the human vanity going astray until insanity.”

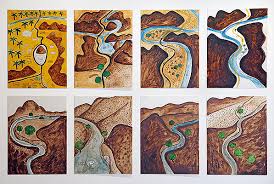

Pictured here is Monet’s The Houses of Parliament, one of nineteen that he did between 1899 and 1901. He produced all of them from the same spot, on a balcony of Saint Thomas’ Hospital across the Thames from Parliament. He painted at different times of day and during different seasons. There is an object in the scene, the buildings of Parliament. But that object dissolves into an almost unidentifiable abstraction. What Monet highlights is the different feeling one can have before the same object.

There appears to be someone floating down the Thames. The same year that Monet painted his first view of Parliament and the Thames, Joseph Conrad wrote Heart of Darkness. It is a novel heavily influenced by the Impressionist view about reality. We meet the main character, Marlow, on a boat on the Thames. The narrator paints the setting for us: “We looked at the venerable stream not in the vivid flush of a short day that comes and departs for ever but in the august light of abiding memory.”

Marlow embarks on a journey into the heart of darkness. On one level, it is a journey into the jungles of Africa where Marlow confronts a character, Kurtz, morally decomposing because of his implication in colonialism. To emerge out of the physical geography, however, is not to leave the heart of darkness. It dwells in all of us.

Our Torah portion, Parshat Ki Teitzei, is full of laws. It has more than any other Torah portion. Yet, it is not those well-defined items that Torah insists that we remember. It is the journey itself. And what we are to recall about it may depend on how we have perceived the journey.

“Remember what Amalek did to you on your way of going out from Egypt…blot out the memory of Amalek.” As a matter of objective history, Amalek as a nation no longer exists. They have been blotted out.

But Amalek’s presence in the life of the Israelites was immediately preceded by a crisis of heart among the Israelites. The Israelites succumb to anxiety and doubt. They question the very value of leaving Egypt. They cry out: “Is God present among us or not?”

That crack in their sacred will opens the door for Amalek to enter among them. Read that way the story’s focus is not on an external enemy but on an internal one: the dark fears that lurk within each of us waiting for a crack to spill forth and consume us.

Monet highlights for us not the literal but our spiritual and psychological encounters with the literal. Conrad reminds us that within us is where we find fields of battle to contend with the darkness that ravages and enslaves the world. Parshat Ki Teitzei calls on us to remember that the sacred journey does not end with settlement on a particular piece of land, for the story is not just about the Israelites. It is our story also. It is not only the Israelites who are on a journey home. We are too.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday August 24 as we explore in the august light of abiding memory.