Torah reminds us that the true site of promise lies within us and that its fulfillment requires a new way of seeing. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

keep a small notepad on my desk. On it I write down tasks I need to do: people I need to call, things I need to fix, projects that require attention. Without that list, I know there are things I would forget to do. And that could create a problem.

In college I was a history major. It was fascinating to study the relationships between countries, the cultural shifts within nations and how those shifts affected the everyday lives of people. Except, I did have a hard time remembering dates, names, and details of events. That was a big problem, especially at exam time.

Every profession, trade and craft has information about how to do things that practitioners need to be able to remember. Sometimes things can be looked up, but there is a lot that one is expected to remember how to do: what kind of stitch to use in different sewing projects; which kind of knot to use when securing a boat to a pier and which to use in wrapping a cover to a sail; what different vital signs mean during the course of surgery. Not remembering these can lead to varying degrees of disaster.

Torah contains a lot of rules governing our conduct: 613 of them. This week’s Torah portion, Ki Teitzei, has the most of any portion: 74, which is twelve percent of the total number. Some of Torah’s laws are no longer applicable, and many can be looked up when needed. But especially for those who are regularly observant, it is critical to have immediate recollection when one is, for example, about to eat or to observe Shabbat.

This same Torah portion with the highest number of laws also contains the insistence: “Remember! Do not forget!” In the context of the narrative, that instruction refers to wiping out the memory of Amalek, who had led an attack on the most vulnerable Israelites during their trek across the wilderness. In Jewish tradition, Amalek represents the capacity to cool humanity’s most inspired ardor with cynicism, senseless doubt and lack of caring. The exhortation in Parshat Ki Teitzei is not directed at remembering the many laws contained in it. It is an admonishment to overcome the fatalism about life and sense of apathy toward others that so characterized surrounding cultures.

On the verge of entering the promised land, Torah loads the Israelites up with the many administrative and ethical rules needed to construct a healthy and successful sovereign state. It also teaches them an essential lesson about how to sustain and develop themselves as spiritually developed human beings: remember. Here, remember refers not to a recollection of dates and places but to the primary mission of a human being: to act responsibly and with care and compassion for all of creation. It is a different way of seeing one’s place and obligation in the world than what they had seen practiced by others.

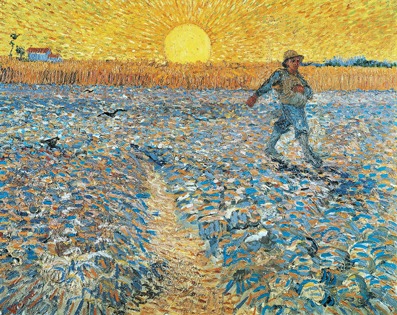

Vincent Van Gogh’s first chosen career was that of a preacher. He ministered to a mining community in Belgium, but after two years his sponsoring church let him go declaring that he wasn’t suited to the profession. Van Gogh turned to art instead, but he carried with him and into his paintings his spiritual yearnings. With his vibrant colors and kinetic brushstrokes, he revealed aspects of both the natural and the human world that were ever present but overlooked.

In The Sower at Sunset Van Gogh paints a sun that is beyond incandescent. Its life-giving radiance extends to and imbues itself into all of creation. The extraordinary colors of the field disarm us from viewing it casually, as a mere representation of what we expect to see. And under that radiance and in that field of imagination the farmer becomes a sower of the sacred. He, and Van Gogh as his painter, restores for us a sense of awe.

Abraham Joshua Heschel proclaimed that this was the true purpose in Judaism of the injunction “remember!” It is a reawakening of awe, that we may “feel in the rush of the passing the stillness of the eternal.” Torah and Van Gogh teach us to see in the ordinary a sense of the extraordinary. As the Israelites rush to load their pack animals and wagons for the final push into a geography of promise, Torah reminds them that the true site of promise lies within them. And that to fulfill the promise depends more on how one is than where one is. “My destination is no longer a place, but a new way of seeing” (Marcel Proust).

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PDT) Thursday September 8 as we explore a new way of seeing.