Beyond all the decrees, directions and instructions there is the story itself. Of a people journeying from dependency to freedom, from passivity to responsibility. Remember the story and you’ll find your way home. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

Law seeks to clearly define behavior that is subject to punishment. It spells out the consequences for engaging in such conduct. One of the primary roles of parenting is to guide children to the departure point of adulthood by teaching them the difference between choices that lead to harm and unhappiness and those that increase possibilities for well-being and fulfillment. And yet, with all these guideposts from both community and family, do we always know which way to go? Are they sufficient to ensure a good choice?

For seven months now we have read the story of the march of the Israelites from Egypt to the border of the promised land. For them it has been a journey of forty years. Along the way there have been signs and portents, decrees and instructions, commandments and teachings. With just a few portions left before the close of Deuteronomy, Torah intensifies this week the lesson about the consequences of making bad choices.

The Israelites are to receive a combined aural and visual message. As they cross the Jordan River they are to march between two mountains: Ebal and Gerizim. Ebal is a rocky and barren terrain, where little grows. Gerizim is lush and fertile. The priests are to recite blessings as the people look toward Gerizim, and they are to proclaim curses as the people gaze upon the desolation of Ebal. While the blessings are few but expansive in scope, the curses are detailed and stunning in number: ninety-eight. Could the choice be any starker?

In 1922 the English writer and artist D. H. Lawrence came to the United States. The following year he wrote Studies in Classic American Literature, a collection of essays on American authors of the 18th and 19th centuries. Lawrence drew a sharp distinction between author as conscious moralist and author as unconscious artist. The former does little to engage a reader in self-exploration and transformation, he wrote. The latter, however, enlists the reader in a struggle for self-knowledge and growth of character.

Lawrence insisted that at times an author’s explicit, didactic intentions are at variance with the narrative they have crafted. Despite their conscious efforts to promote a particular lesson, something escaped from a subterranean realm of the writer and made its appearance in the narrative. When that happens, Lawrence wrote, “Never trust the artist. Trust the tale.” Disregard the author’s declarative voice. Attend to the story for a journey into the human struggle for being.

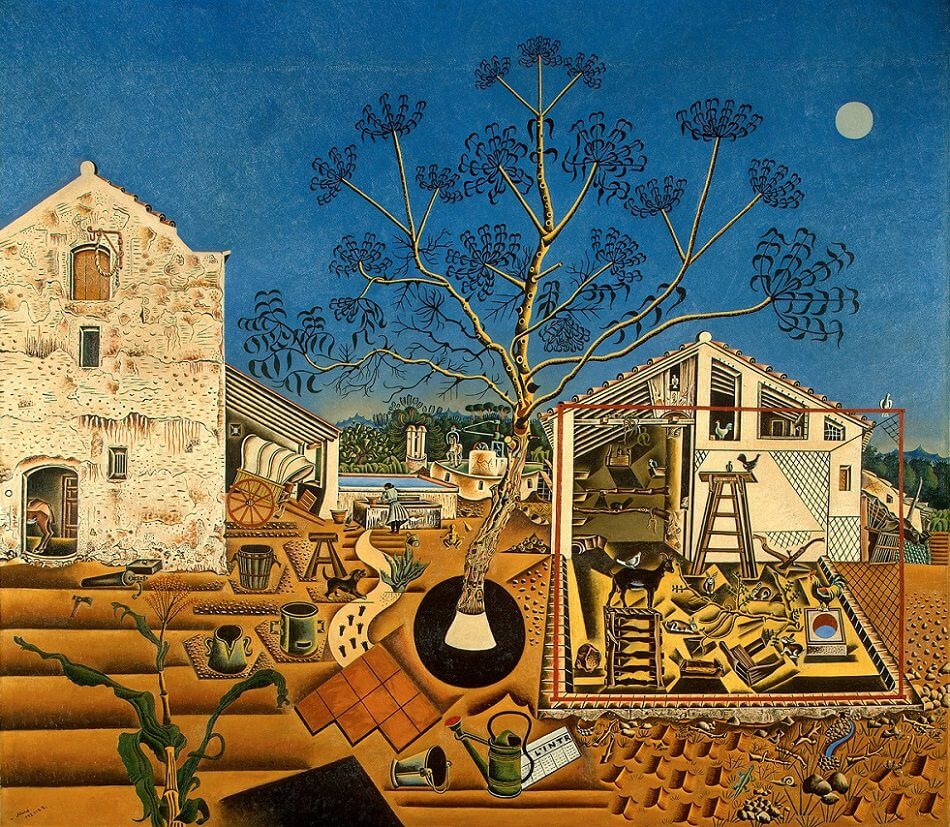

The same year that Lawrence toured America, the Spanish artist Joan Miro spent nine months painting his piece The Farm, presented here. The scene depicts his family’s farm in Mont-roig del Camp, Spain. Miro assures us, “the painting was absolutely realistic. Everything that’s in the painting was actually there. I didn’t invent anything. I only eliminated the fencing on the front of the chicken coop because it kept you from seeing the animals.”

Still, the narrative on the canvass seems to tell us something beyond the literal. Elements of the scene indicate that is midday. The sky is an intense blue, but there are no shadows. The sun is silver gray. Or perhaps that is the moon, and it is nighttime. A twisting carob tree dominates the foreground. Half alive? Half dead? A goat on a pedestal with a bird on its back. A wagon standing on a single wheel. John Updike observed, “the painting is possessed by an ecstasy of simple naming, a seemingly innocent directness that is yet challenging and ominous.”

Innocent or ominous, of this world or otherworldly, the painting was for Miro “a resume of my entire life in the country.” After this painting Miro shifted to Surrealism. His subsequent canvasses, dedicated explorations of the unconscious, were rich in color, full of biomorphic shapes and absent of any human forms. The Farm would be for Miro his path back home. Rich in detail, colored by memory and longing. And full of meaning and orientation.

The book of Deuteronomy is rich in didactic instruction. Yet, ultimately it is a story retold, of the journey the Israelites have been on for forty years. And throughout that journey, stretching back to the beginning of it all, Genesis, has been an overriding theme: covenant. Noah experienced. Abraham partook of it. The entire line of ancestors entered into it. The Israelites as a nation trembled at its seismic entrance into their communal life.

Yet, each reference to covenant seems to describe a slightly different dynamic: a pledge of no more destruction; a promise of a great and expansive family; a statement to work divine wonders; a commitment to wipe out Israel’s enemies; tablets with writing on them; and something called Torah.

Each generation discovers a new meaning of covenant, one that facilitates its own evolution homeward. What promotes that discovery is hearing deeply the story. Absorbing it. That, after all, was the driving purpose behind the exodus from Egypt: “That you may tell the story to your children and your grandchildren.” All you need to know is in it. Trust the tale.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday August 31 as we explore trust the tale.