To become truly free is more than an instantaneous release from constraint. It involves practiced growth and development. The fruit of that harvest is a rich offering to share with all. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

Among the many bold experiments launched by the founders of our country was the disentanglement of government and religion. The leading drafters of the United States Constitution were children of the 18th-century Enlightenment. They stressed reason and scientific observation as a means of discovering the nature of the providential force that had created the world. From that point of view, religion exercised a restraining influence on social, civic and scientific progress. While valuing the personal benefit of religious thought, the founders disconnected the mutually powerful forces of governance and religion.

This separation was a radical break from the European model in particular. To this very day the British monarch is also the Head of the Church of England. A counterpoint to this disengagement between government and religion is the First Amendment right to practice any religion and to express any belief. Determining what is an acceptable form of religious expression in a governmentally funded setting has challenged federal courts since the 19th century.

In 2015 the coach of the Bremerton, Washington High School football team walked to the 50-yard line at the end of the game. He knelt and prayed. The school district fired him, arguing the coercive effect he had on those he coached. He maintains that he did not ask or require any students to go with him and that he has a right to pray privately on a school football field. The United States Supreme Court heard oral argument on the case last month.

The Jewish community in the United States, as a minority religious group, has generally been supportive of a separation between government and religion. Yet, the thrust of Judaism for centuries has been to infuse every aspect of daily life with the lessons of Torah. Is the harvest of my Torah learning to be offered only in a setting defined as religious? Or can it be brought outside those walls into the public sphere as a living faith?

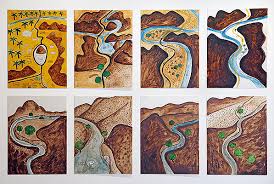

In Parshat Kedoshim we read beautiful language about our responsibilities towards others in our everyday encounters and transactions. Even more poetically, we read about the values of different years of fruit growth. The produce of the first three years of a tree’s life is to be left alone. The fourth year’s produce is set aside as holy and is to be eaten only within the walls of Jerusalem. However, the fifth year fruit can be eaten anywhere by anyone. The fourth year fruit is called “holy,” separated from the rest. However, the fifth year fruit is considered the most precious. To share beyond the walls, beyond what has been set aside “more richly increases its yield” for us.

Paul Cezanne was fascinated with fruit. He painted nearly 200 still lifes with fruits of all kinds: apples, pears, grapes, pomegranates. “I will astonish Paris with an apple!” he wrote. With these simple subjects Cezanne radically altered perspective and launched what became modern art. The objects on his canvasses seem to have no certain balance or single dimension to them. Whatever equilibrium there is results not from their integral reality but from the artist’s insistent hand. What is holy about them is not merely their inherent quality but what he did with them.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PDT) Thursday May 5 as we explore fruit of the fifth year.