Faith in Judaism is a creative, artistic endeavor. Torah invites each of us to become artists. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

Traumatic shocks to our system can us lead to a search for clear answers to our question “Why?” We may experience this on the personal level with a life-altering loss. The tragic death of someone dear to us. The collapse of our financial means of support. A progressively disabling disease. On a social level, whole groups may sense a reversal of their status. Entire industries disappear. Traditions and values once triumphant seem devalued. Our desire for clarity of cause and certainty of direction might cause us to embrace rigid and singular answers. If we do so, our capacity to adapt and to tolerate diminishes. As does our chance to successfully emerge from the inevitable catastrophes of life.

Parshat Chukat paints a picture of the Israelites experiencing a series of devastating shocks. They are still reeling from the horror of having witnessed hundreds of their relatives being buried alive for having dared to challenge the authority of Moses and Aaron. Thousands more died from a plague for the same reason. Now they experience the deaths of Aaron, their spiritual leader, and Miriam, the source of miraculously appearing water in the wilderness. Perhaps the greatest shock is the announcement that Moses would not lead them into the promised land. He is to die in the wilderness.

The text itself has moments of agita, as if in sympathetic response to the anxiety of the Israelites. A verse shatters and appears in only fragmented form, containing words that seem non-sense: “Waheb” and “Suphah.” There is reference to a previously unknown annal, the “Book of the Wars of Adonai.” What is that!? The order that had marked the opening of the Book of Numbers, with all of Israel organized into tribes and families and arranged into a set line of march, now seems on the edge of disintegrating back into chaos.

Haunting the entire episode is God’s condemnation of Moses for not having enough faith in God by not following precisely God’s instructions for providing water for the people. The Hebrew word used here for “faith” is emunah. This word shares the same root as the Hebrew word aman, “artist.” In Judaism faith has a distinctive nuance. Some religious traditions are doctrinal. They emphasize learning doctrines constructed from sacred texts. By contrast, Judaism is interpretive. It emphasizes learning how to tease out and innovate new meaning from sacred texts. Faith in Judaism is a creative, artistic endeavor. Tradition is one of the materials with which to work.

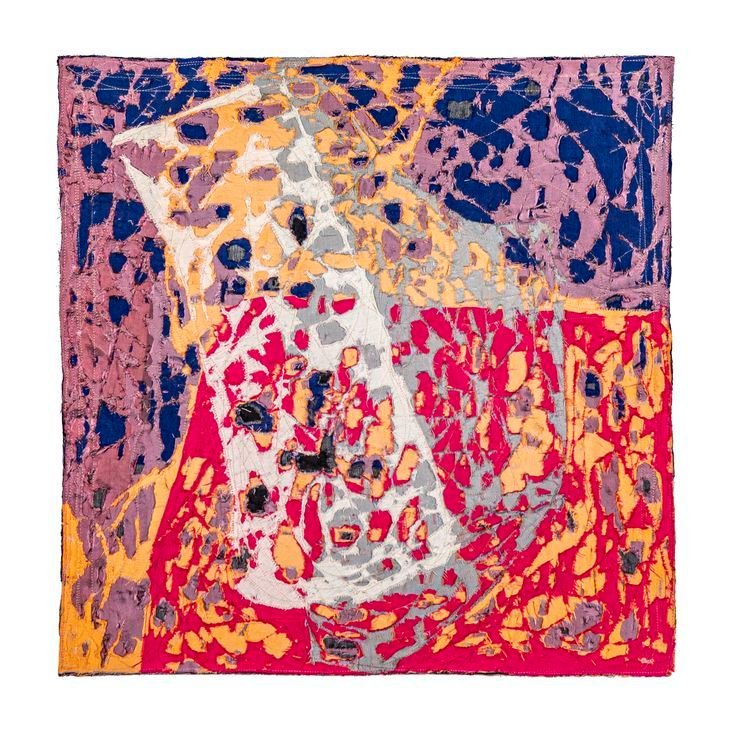

Vaishali Oak is a fiber artist born in 1970 in Pune, India. Driving past a settlement of nomads one day, she paused to admire their patched quilts. These were works of a traditional sewing practice called “godhadi,” consisting of old fabrics layered and frayed from use and re-use and patched with varied colorful bits of cloth. Oak stared at the works of tradition and saw in them forms of her own modern artistic expression, about which she has said: “My works are not representational. There is no recognizable thing, like flowers or clouds. Since childhood we are taught to link words with objects, but it is when we don’t say with words that we begin to communicate through feelings. When people see the works in Chromatic Musings, they connect it with their own visual and vocabulary experiences. By spontaneously rending and distressing the fabric, I create a sense of drama that draws in the viewer and intensifies their sensory reflections by drawing on stored memories.”

The climax of Parshat Chukat is the moment before a rock from which Moses is to draw forth water. God’s instruction is that Moses do this “before the very eyes” of the Israelites. This is meant to be a visual work, one that would draw in and transform each Israelite according to their own viewing experience. The life sustaining force to be unleashed is not merely the water from the rock. It is the creativity from within each person present.

That artistic power finds fulfillment in the Torah portion when at its end the Israelites become the ones to bring forth water.They do so by singing a song. Immediately thereafter they are able to accomplish what Moses himself had failed to do just a chapter earlier: overcome their enemies. The traumatic elements of the story resolve not in the people’s surrender of their power to another or in an embrace of narrow thinking. They burst forth in creativity, in a way that exceeds even their great teacher. They discover that for the community to dwell within the land of promise, each resident must become a source of flowing innovation.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PDT) Thursday July 7 as we explore the faith of interpretation.