To be a source of liberation we need to first confront our own fears and layers of self-protection. View study guide here. Watch recording here.

The planet Dagobah as presented in the Star Wars saga is a place of murky swamps, steaming bayous and overgrown jungles. It is a dark and forgotten world. Yet, it also teems with life and is rich with that power which binds all existence together. Luke Skywalker is instructed by his spiritual master Yoda that before he can go forth to lead people in a battle for freedom, he must enter the cave of Dagobah and overcome his greatest enemy. “What’s in there,” asks Luke. “Only what you take with you,” replies Yoda.

Yoda understands the spiritual choreography which Luke needs to follow before he can be free enough to be a source of liberation. First, he must enter into the shadowy realm that lies beneath the surface of his consciousness. Only after having confronted his fears and psychic contusions can he go forth on his mission successfully.

This prescribed flow of steps is at work in this week’s Torah portion, Bo. Three different words are used in it to convey movement. They appear in a distinct order, creating for those who seek it a graceful flow to true liberation.

The opening word, bo, is often translated as “go,” renderingGod’s instruction to Moses as “go to Pharaoh.” Yet, as the Zohar, Judaism’s primary mystical text, points out, a literal translation would be “come to Pharaoh.” Before he can be a source for liberation, Moses must enter into the realm that is Pharaoh. What he encounters there is a toxic dimension of cruel oppressive power, a thick overlay of materialism, and contempt for the ordinary. As one who grew up in the palace, Moses had absorbed all of that.

The second word of movement in the portion is “go out.” It is the same word that is used to describe Noah and his family leaving the ark. They were sequestered there for forty days, a period evocative of contemplative retreat and renewal. In this week’s portion the Israelites are instructed that they must remain within their homes before they can “go out.” They have had their own experience with Egypt/Pharaoh which they must reflect upon and purge if they are to become free.

This choreography of liberation climaxes with the third word used to describe movement: “go forth.” This is the word that describes Abraham’s entrance onto the path of sacred purpose. He embraces his mission, having rejected a world of false perceptions and vain pursuits.

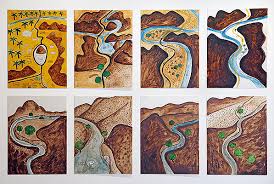

Parshat Bo notates for us a sequence of steps for a successful flow to freedom: enter into yourself; emerge after scanning and mapping your internal landscape; go forth in new purpose.

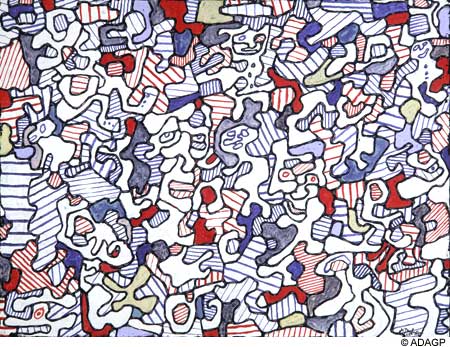

Jean Dubuffet was a mid-twentieth century French painter and sculptor. While greatly influenced by the Surrealists and their exploration of the subconscious, Dubuffet added to that an embrace of “outsiders” to the approved art world: untrained artists including, psychiatric patients, prisoners, and children. He championed their immediacy, rawness, and focus on everyday life.

His own works often convey a cramped and emotionally disturbing feeling. There is a brutal beauty present in his paintings. Something is struggling to be born. His focus on untrained artists, his use of found everyday materials and his insistence on uncovering what lies beneath the surface led him to call his approach Art Brut (Raw Art). He identified the culture of those in power as an ill-fitting irrelevancy to most people. “The real function of art,” he wrote, “is to change mental patterns, making new thought possible.”

His painting Comings and Goings appears as a mass of figures chaotically pressing upon one another. It is a brutal reality of the moment. Yet within it, as the title hints, is the possibility of a new present emerging. What is key is to know the order of movement: our comings and goings.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday January 26 as we explore comings and goings: the choreography of Torah.