“They say – and I am willing to believe it – that it is difficult to know yourself – but it isn’t easy to paint yourself either.”

View the study sheet here. Recording here.

Rembrandt produced forty self-portrait paintings. More than any other artist. He did these over a career that lasted four decades. Vincent van Gogh painted thirty-six self-portraits. He created those over a 10-year period.

In part, van Gogh turned to self-portraiture out of economic necessity. He was too poor to afford models. More compellingly, his work with self-portraits was part of his search for that truth which lies beyond the surface. “The portraits painted by Rembrandt,” he wrote, “are more than a view of nature. They are more like a revelation. To try to understand the real significance of what the great artists, the serious masters, tell us in their masterpieces, that leads to God. One man wrote or told it in a book; another, in a picture.”

Van Gogh initially expressed his pursuit of revelation, of the presence of the divine, as a Christian preacher. After working for ten years as an art dealer, van Gogh left the business world and received a commission from the Belgium Missionary Society to serve as a preacher and missionary to coal miners in Belgium. While there he gave away his lodgings to a homeless man and moved into a hut near the workers where he slept on a bed of straw. Having impoverished himself, his health deteriorated. The church dismissed him, citing his “overly enthusiastic” commitment to his faith.

Van Gogh returned to his family home, where he taught himself to draw. His original palette was dark and somber, often portraying the gritty life of peasants. In 1886 he moved to Paris, where he immersed himself in the new art forms being innovated by the Impressionists. Camille Pissarro in particular helped van Gogh to brighten his palette. He mentored van Gogh in how to juxtapose complimentary colors to achieve greater luminescence.

After two years in Paris, van Gogh moved to Arles in southern France, where the light was brighter and where he hoped to create a community of artists. Within a year, he suffered a mental health crisis and committed himself to a psychiatric facility in nearby Saint-Remy.

During that year, van Gogh produced some of his most revolutionary and spiritually infused work, including Starry Night. That work was produced not while in the field, but entirely from his memory and imagination. It is a scene of nature that portrays a dimension beyond the physical world.

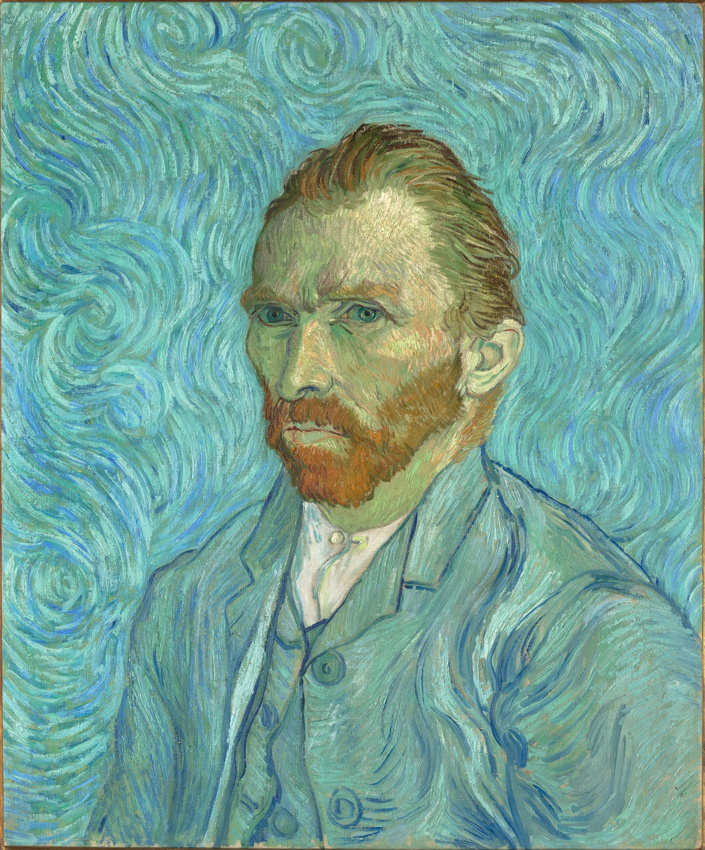

The same year as Starry Night, van Gogh also painted the self-portrait pictured here while at Saint-Remy. The colors absinth green and pale turquoise give shape to his dress suit jacket and vest. And those same colors swirl around him in a flurry of energy reminiscent of the sky in Starry Night, hinting that there is more than the physical made manifest here. In sharp contrast to the greens and blues are the reds of van Gogh’s beard and hair. And his face is all of those colors…and more.

What shall we make of his visage, his expression? Is this a man in pain? The presentation of a tortured soul resident in a psychiatric hospital? Or is this van Gogh as missionary, this time not to a community of miners but to his own self and soul?

At the time of this painting, van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo: “They say – and I am willing to believe it – that it is difficult to know yourself – but it isn’t easy to paint yourself either.” Despite the difficulties, van Gogh was compelled to do both. He knew that both the penetration of self-imposed lies and fears in order to reach one’s core self and the presentation of that self to others is a matter of divine revelation.

The climax of Parshat Beshalach (“when Pharaoh let go”) is the crossing by the Israelites of the Sea of Reeds, called in Hebrew the Yam Suf. The word suf (“reeds”) is built from the verb “to cease, to come to an end.” In Ecclesiastes suf kol ha’adam means “the end of every human,” that is, “death.” This is no mere physical body of water Torah is describing, just as it was no mere sky that van Gogh painted. Yam Suf offers the Israelites an opportunity to leave their internalization of Egypt behind, to purge themselves of its dark grip on their souls, psyches and behavior.

Two songs are sung upon the crossing. One by Moses and the men. The other by Miriam and the women. Moses calls out, “We shall sing…” Miriam shouts, “Let us sing!” One is in the future tense. The other is imperative (“sing now!”).

In a radical reading of those two songs, the late 18th century Hasidic rabbi Kalonymous Kalman Epstein describes Moses as stuck in a linear world, where distinctions between upper and lower, between masculine and feminine exist. Miriam, by contrast, has crossed over into a new dimension: where “there will no longer be the categories of masculine and feminine;” where circles of inclusion prevail over lines of power and distinction…“where every part of the circumference is equidistant from the center.”

James Baldwin, the great African American writer and civil rights activist, insisted that the creation of a just society requires individuals who are vigorously courageous in exploring their personal “unchartered chaos” and in confronting and overcoming their internal narrowness. Echoing van Gogh, he wrote: “Anyone who has ever been compelled to think about it knows that the one face that one can never see is one’s own face.” Yet, that exercise is critical for the collapse of walls of fear and for the growth of fields love.

Torah acknowledges that the obstacle that separates a life lived in fear from one lived in love is wide and deep. Yet, it holds out the promise of a song upon its crossing. One that we sing in the moment as the power-built barriers evaporate and are replaced by circles of care and compassion.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) on Thursday February 6 as we explore crossing the deep.

Oil on canvass Self-Portrait by Vincent van Gogh (1889)