Torah is not a call to perfection. It is a summons to a life of ongoing improvement, for the sake of all. It is a call to liberty and its responsibilities. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

The founders of our country stated that they were creating a system of government that was not only perfect. It was “more perfect.” It says so right in the preamble to the Constitution: “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union…” But just three paragraphs later, the Constitution states that enslaved Americans would be counted as three-fifths of a person for taxation and representation purposes. Hardly perfect, much less “more perfect.”

Thirty-five years before the final drafting of the Constitution, the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly commissioned a bell. On it were inscribed words from this week’s Torah portion: “Proclaim Liberty Throughout All the Land Unto All the Inhabitants thereof.” On July 8, 1776, that bell rang out, summoning the people of Philadelphia to the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence, which included the words: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” Neither the bell nor the declaration seemed to ring true, as evidenced by the Constitution’s subsequent endorsement of inequality.

What are we to make of this dissonance between declaration of value and constitution of actual governance? Did our founders think they were actually designing a perfect form of government? Can we view their expressions of “liberty for all” and “all men are created equal” with anything other than a sense of betrayal of purpose or disappointment at their shortcomings?

The book of Leviticus, the source for the Liberty Bell’s verse, is a pause in the journey of the Israelites. The frantic rush out of Egypt toward the promised land comes to a narrative halt with its opening verses. The drama of Torah’s earlier two books is replaced by instruction of various kind. It is a good time to reflect, to look in the mirror.

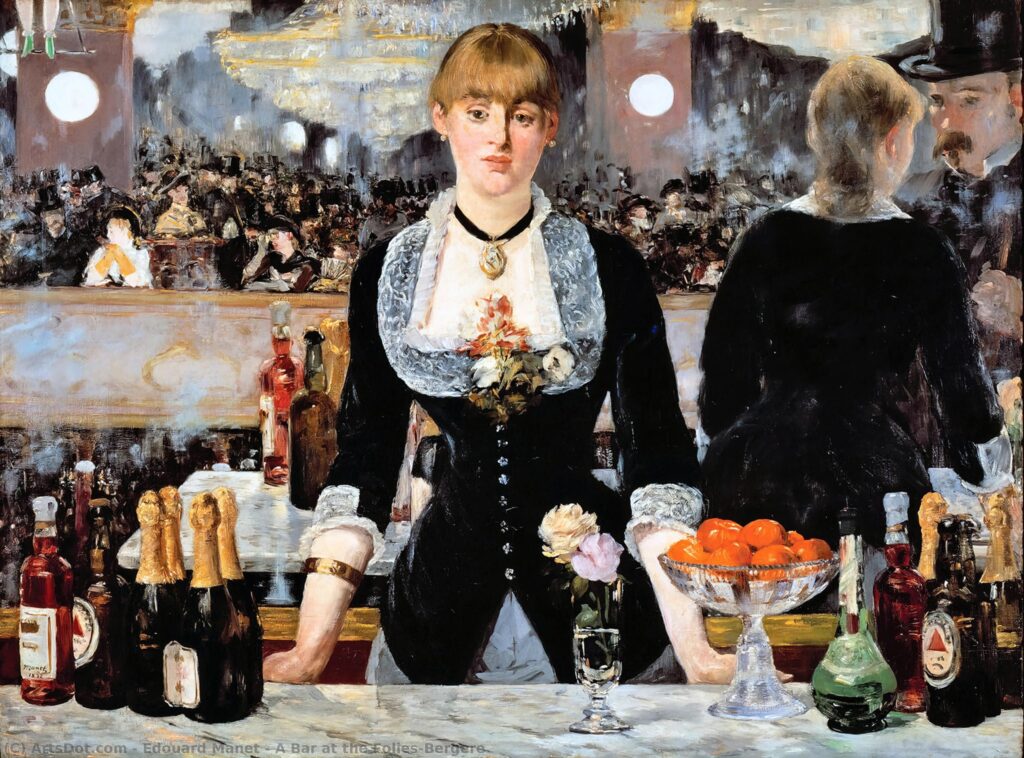

Pictured here is the last major work by Edouard Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergere. At the painting’s center is a barmaid looking straight ahead. Yet that viewpoint is contradicted by the reflection in the mirror of objects on the bar and the figures of the barmaid and a patron off to the right. Manet’s perspective seems distorted, imperfect.

*A Bar at the Folies-Bergere *was exhibited at the 1882 Salon, the venue for paintings officially sanctioned by the French art establishment. Dominating the Salon exhibitions were works emphasizing messages of moral uplift, through themes from mythology, history and religion. Manet’s painting was unsettling for upper-class Parisians, both in style and in subject matter.

The Folies-Bergere was a place of spectacle and morally suspect behavior. It was widely known to be a setting for prostitution. The painting’s central figure is not drawn from mythology or history or the Bible. She is a common bartender. The flowers she wears are arranged in a triangle. That shape is replicated in the logo on the bottles of Bass beer, constituting perhaps the first instance of product placement in a work of art. Manet promotes the theme of consumerism further by inscribing his own name on the label of the bottle at the far left.

Distorted perspective. A scene of abandon. Hints of prostitution. A commoner commanding central attention. Consumerism. All contribute insult to the then dominant standards of artistic perfection. Yet, there is also great beauty there. And Manet has drawn us into the moment. The barmaid is looking at us even as she is simultaneously engaged with the man in a top hat. We are implicated in the transaction between them, and thus in the entirety of the setting. Manet shows us ourselves as participants in a world of distortion, commonness, perhaps even degradation. And beauty.

Our Torah portion trumpets words of liberty even as it details rules for how to treat slaves. To be “in the image of God” is not to be perfect. It is to be summoned to an ongoing pursuit of elevation. “To form a more perfect union” both acknowledges that what currently exists is not perfect and expresses confidence in our capacity to engage in a process of continuous improvement. And Manet reminds us that imperfection can be the setting in which to discover dignity and great beauty.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday May 11 as we explore the holiness of imperfections.

Oil on canvass A Bar at the Folies-Bergere by Edouard Manet