The flow of a free life is to return to the source of one’s origin, with the result that neither is the same as it once was. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

THE FLOW OF FREEDOM

Torah has two words for freedom. One is chofshi. It is used in connection with the freeing of slaves: “a slave may serve six years; in the seventh the slave shall go free (chofshi)” (Exodus 21:2). This kind of freedom refers to being cut loose, unshackled.

Modern philosophers term this kind of freedom “negative freedom.” It is freedom from something. Negative freedom defines the unencumbered self, one who does not need to be part of a group in order to have identity. The Bible hints at the negative aspects of this extended detachment: “I am numbered among those who go down to the Pit/I am helpless/adrift (chofshi) among the dead/Cut off from God’s remembrance” (Psalm 88:5).

The other word Torah uses is found in this week’s portion, Behar: dror. It is used in connection with the Jubilee year: “You shall proclaim liberty (dror) throughout the land unto all the inhabitants thereof” (Leviticus 25:10). Those words are engraved on the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia, which became a symbol of an emergent nation’s enterprise to constitute a new vision of civil society based on expanding rights and a widening of the scope of who is a citizen.

Dror is based on the Hebrew verb meaning “to flow abundantly.” This stream of fruition is specifically connected to the Jubilee (Yovel) year, when all slaves are to be emancipated, all ancestral land that had become alienated by sale or debt is to be returned to their tribal allocations and all people who had become dislocated because of economic difficulties are to be restored to their original land apportionments.

The word yovel is built upon the Hebrew verb “to bear along.” Variations on that root also give us the words “watercourse” (yaval), “ram’s horn” (yovel) and “world” (tevel). The 14th century Spanish kabbalist Rabenu Bechaya wrote, “yovel means ‘rivulet,’ as in during Yovel everything flows back to its original source.” Here freedom is not departure away from. It is a restorative return to creative origins. It is not separation but reconstitution.

This reconstituting flow that is Yovel is proclaimed by the musical notes of the shofar. And it is a time that is pronounced kadosh, holy. It is a separation from the ordinary for the purpose of attachment to the divine.

By the end of the 19th century, artists had freed themselves from the rules of classical art, which prescribed how subjects were to be portrayed. Impressionists replaced replication of physical reality with their subjective experiences of the world. Post-impressionists such as Cezanne explored multiple points of view on a single canvass. Cubists disclosed the many planes of dimensionality of their subjects.

At the turn of the 19th century a handful of artists across Europe began to paint without reference to the external world. This new abstract art form, which would come to dominate the 20th century, transcended the identifiable figure and object altogether. The subject matter of these artists was the spiritual dimension of existence.

For most of the 20th century scholars regarded Wassily Kandinsky as the pioneer of abstract art. The publication of his book Concerning the Spiritual in Art in 1912 highlighted his pioneering role in freeing art from its traditional bonds to material reality. In it he explained that art was “one of the most powerful agents of the spiritual life.” It has been only in the last thirty years that scholars have reconsidered whom to call the first abstract artist.

Hilma af Klint was born in 1862 in Sweden. After graduating from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm in 1887, she set up a studio and gained recognition as a landscape and portrait painter. She also began attending meditative sessions convened by the spiritualist Theosophy movement, one that was particularly welcoming of women.

In 1905 she noted that in the course of her spiritual practice she heard a voice guiding her on what and how to paint. Between 1906 and 1907 she painted a series of abstract canvasses titled Primordial Chaos. This was five years before Kandinsky painted his first abstract piece.

Af Klint noted that spirit voices subsequently assigned her to produce a large series of artworks called Paintings for the Temple. She saw herself as a channel between the spiritual and material worlds. As part of that series, she was guided in 1907 to paint ten paintings titled The Ten Largest. The voices instructed her to paint each piece over a four-day period. Over forty days exactly af Klint completed the series of ten paintings.

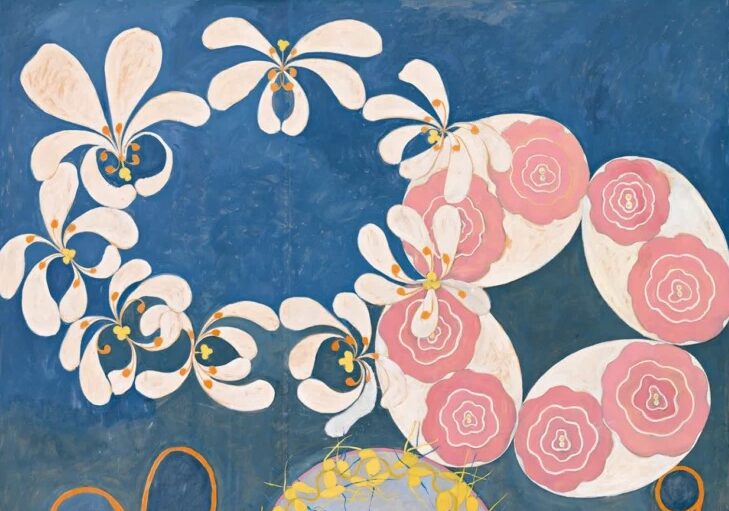

Pictured here is The Ten Largest, No. 1. As a series, the ten paintings express the evolution of a human through four different stages. This first in the series is one representing childhood. According to af Klint the canvass is full of distinct principles. Blue represents the feminine, while rose and yellow symbolize the masculine. For af Klint what appears as dualities in colors and forms are really forces in the process of integration. The organic nature of the forms anticipates not their separation but their evolving reconstitution into a higher state.

Abstract art, pioneered by af Klint and others, became a vehicle for artistic exploration of the divine dimension. Released from any requirement to replicate recognizable material reality, abstract artists were freed to explore both the profoundly transcendent and the deeply internal. And for many, the discovery that the two realms might flow together was tremblingly revelatory.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) on Thursday May 23 as we explore the flow of freedom.