To confront our fears and our weaknesses is the work of heroes. It is how we get home, to a life undivided and sovereign. View the video zoom recording of this parshat here. View the commentary here.

What makes a hero? Heading toward danger to save others seems like a good basic starting point. Some people are in professions where placing oneself at risk in order to save lives is an expected response to a threat. Others seem to just have it in their character to step forward to defend the vulnerable, aware that there is a personal risk and do so without expectation of reward.

Is it possible to train people to be heroes? Dr. Philip Zimbardo, a professor emeritus of psychology at Stanford University, adamantly believes so. He is the founder of the Heroic** **Imagination Project (HIP), a nonprofit research and education organization dedicated to training people to act in more heroic ways. HIP evolved out of Dr. Zimbardo’s study of the psychology of evil as part of the Stanford Prison Experiment. A key finding of his research is that the same situations that inflame the hostile imagination in some people, making them villains, can also instill the heroic imagination in other people, prompting them to perform heroic deeds. “Each of us may possess the capacity to do terrible things. But we also possess an inner hero: if stirred to action, that inner hero is capable of performing tremendous goodness for others,” Dr. Zimbardo has written.

The hero as a recurrent figure in myths across different cultures is the subject of Joseph Campbell’s influential work *The Hero With A Thousand Faces. *Campbell identified a template of the hero’s journey, launched by a call to an adventure. There are a series of trials ending with the hero securing a treasure which the hero brings back for the benefit of his or her community. As a result of the journey, the hero’s character is transformed.

The hero character is in dynamic development in the narrative of the book of Numbers. However, it is not an individual who is the protagonist. It is the nation of Israel. Challenged to depart from the constraint that is Egypt, Israel begins its journey of freedom. The initial vista where Israel encamps is the world of Leviticus. It is a land shaped by clear boundaries. It is a still place, with virtually no development of character. Israel moves on into the very different landscape that is Numbers, bamidbar, the fearsome expanse where human character is unleashed and tested.

Israel cycles through complaint and gratitude, courage and cowardice, love and hate. In a radical reading of that dynamic, Rabbi Mordechai Yosef Leiner, the 19th-century founder of the Izhbitza-Radzyn dynasty of Hasidic Judaism, wrote: “All the protagonists in the book of Numbers – even the rebels who complain and desire and hate – are of heroic nature.”

Rabbi Leiner’s focus is on the spiritual and psychological development of Israel as it journeys toward wholeness. That wholeness, shalom, can be achieved only through a confrontation with one’s dark and broken self. In Rabbi Leiner’s reading, Israel’s journey is less a matter of history and geography than one of spirituality and psychology. Brokenness is the realm we must encounter and cross to become the whole we were born as and we can become again.

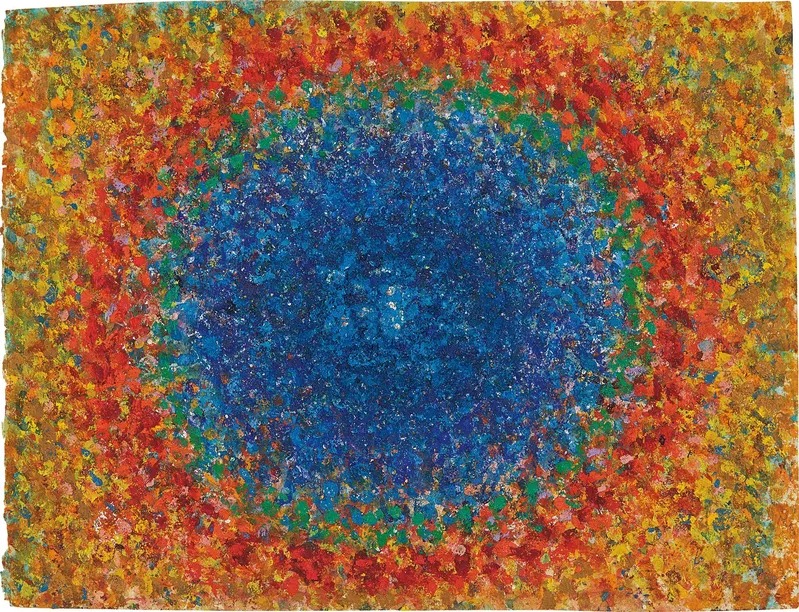

Richard Pousette-Dart was the youngest artist of the New York School’s first generation of Abstract Expressionists. Fascinated with the tension between abundant complexity and singular wholeness, Pousette-Dart produced works that require the viewer to move forward to see the components and backward to see the overall image. Presented here is his painting Center of the World. There is a core of soothing blue, but the surrounding rings of fiery reds and yellows cannot be ignored. Urges and passions flow through the scene. They are part, not a disruption, of the whole picture. Pousette-Dart gives them due presence in his search for wholeness.

Painting for Pousette-Dart is not an act of presenting the pre-determined. What the center of the world might look like is engendered in the course of his work. Only by experiencing and expressing what is found along the way can unity be created and portrayed: “When the brush touches the canvass things happen that we could not know before, and our preoccupations dissolve.”

Pousette-Dart painted paths through density and complexity to a wholeness, to the divine. He pursued the spiritual through the fragments found along the way. “Within or about every living work of art, or thing of beauty, or fragment of life,” he wrote, “there is some strange inner kernel which cannot be reached with explanations, examinations, or definitions. This kernel remains beneath, behind, beyond. It is this dimensionless particle which loves, breathes and means. It is this living particle which makes art mystical, unknown, real and experienceable.”

Rabbi Leiner dares us to acknowledge our dark impulses not as obstacles but as pathways to growing into our fulfilled selves. Pousette-Dart dares us to discover and paint the shards of our broken selves on our way to creating something beautiful and divine. This is the work of heroes.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday June 8 as we explore the work of heroes.

Acrylic on paper Center of the World by Richard Pousette-Dart