The adult world is one of complexity and imperfection. It is where we are called upon not to be perfect but to be responsible. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

We are entering that season of the year full of all sorts of myths that give shape to childhood. The first is the Thanksgiving myth. Its story is that friendly Indians welcomed the Pilgrims to America, taught them how to live in this new land, and sat down to dinner with them. The second is the myth of Santa Claus, who covers the earth in a sleigh pulled by reindeer and delivers gifts of toys made by elves to children onChristmas Eve.

The whole concept of Native Americans and Pilgrims sharing a “thanksgiving” dinner together did not even exist until Reverend Alexander Young conjured it up in a book he published in 1841. And the relationship between the English settlers of Plymouth and the Wampanoag tribe in 1621 was a little more fraught than the image of a friendly sit-down dinner might convey. Still, it is hard to let go of a feast with turkey and cranberries and school plays and greeting cards that convey a sense of warmth and bounty as winter sets in.

Even more pervasive are the images of Santa Claus that begin to appear in our shopping malls, on our television screens and in parades once Thanksgiving has concluded. When and how to tell children that Santa Claus is not real is for many parents a difficult decision to make. It is the theme of countless books and movies. Still, the naivete of childhood must come to an end, right?

That stage of human development comes to an end with Abraham. He leaves behind the dimension that is his youth, his upbringing. He crosses over into the adult world of making decisions, of exploring the world, of staking out his territory. This new dimension he enters results in both acts of heroism and nobility and ones of cowardice and shame. And so it will be for the characters who follow him in Torah. Simplicity has evolved into complexity. And so has the relationship with God. It now involves direct contention and argument as well as devotion and gratitude. Would it be better to return to the simplicity, the naivete of childhood? The myth of the garden rather than the realities of exile?

The world that Abraham begins to shape with his decisions is a far more complex one than the one occupied by Noah. Each of his choices and those of Sarah and all of their descendants will complexify the narrative canvass with layers of their successes and their failures. Does it all add up to a tangled mess, or is there some coherent beauty to be found there?

Such an end to childhood is the theme of this week’s Torah portion, Lech Lecha. The primary character of last week’s portion was Noah. He is described as tam. It is a word with many meanings. One is “innocent, simple.” The stories in the first two portions of the Torah describe humans reluctant to enter the world of responsibility (Adam and Eve), thoroughly self-centered (generation of the Flood), or afraid to leave the protection and familiarity of home (Babel). Noah’s own simplicity is expressed through his total silence in the face of impending disaster.

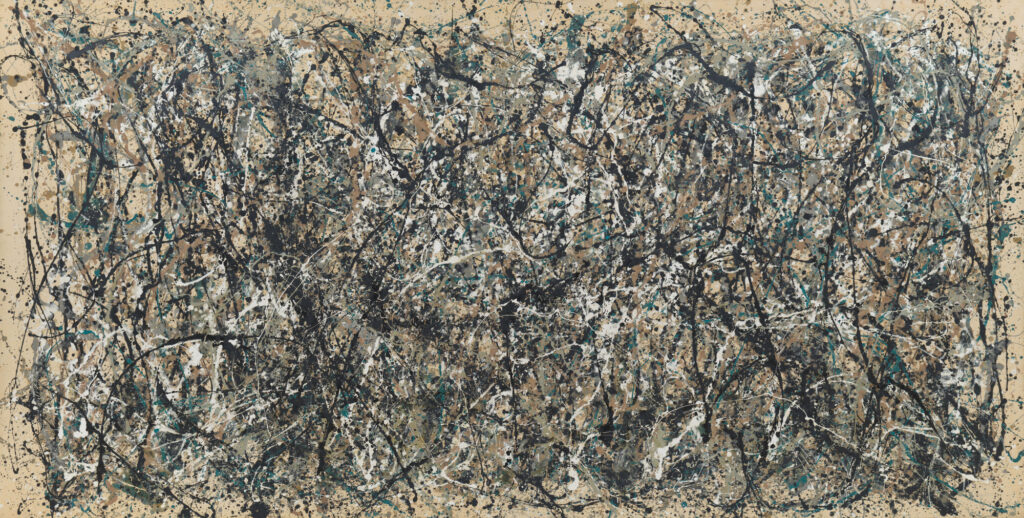

Jackson Pollock changed the notion of what it meant to paint. Removing the canvass from the easel and placing it on the floor gave him an entirely different relationship to it. What ended up on the canvass was no longer the primary art work. The canvass served as a record of the real artistic event: his engagement with the canvass, his choreography around and over it with brush in hand. As he moved about it, he would drip or fling paint onto it.

Early critics condemned his works as “mere unorganized explosions of random energy and therefore meaningless.” And yet, people were drawn to the power, the beauty, embedded in the pieces.

Among those entranced by Pollock’s drip paintings at an early age was Richard Taylor, a physicist. About twenty-five years ago while working on nanoelectronics, he noticed something that reminded him of those paintings. “The more I looked at fractal patterns, the more I was reminded of Pollock’s poured paintings. And when I looked at his paintings, I noticed that the paint splatters seemed to spread across his canvases like the flow of electricity through our devices.”

Fractal patterns are infinitely complex designs which have a similar appearance at any magnification. A small part of the structure looks very much like the whole. They have been observed and only recently replicated as a result of modern computer programming. The study of fractals is a part of chaos theory that has developed over the past half century. Scientists have found that natural systems such as plants, coastlines and weather patterns though appearing to exhibit a random state have beneath them a subtle form of order, one they have labeled as “chaotic” because of how sensitive they are to initial conditions (the “butterfly effect”).

Fractal patterns draw us because of the infinite harmony they present. This is what Richard Taylor recognized about the apparent randomness on Pollock’s canvasses. Underneath the seemingly random drips and splatters are patterns evocative of nature and the chaos that is evidence of life. Pollock achieved this through how he chose to move, the position of his body relative to the canvass, and the speed of his drips. He adopted nature’s generative mechanism: chaos dynamics. In the process, he created works of both great complexity and beauty.

This is the world Torah has now taken us into with Abraham and Sarah. It is the world in which you and I are meant to dwell. We leave behind child-like innocence for the challenge and complexity of adult living. This is where we can become the artists God calls upon us to be.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday November 3 as we explore the meaningful chaos of complexity.