The true measure of freedom is the extent of our obligation to one another. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

Four weeks ago United States Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy released an Advisory that identifies lack of social connection as a public health crisis. In his advisory, Dr. Murthy reports that insufficient social connection produces increased risk of heart disease, stroke, and dementia. Perhaps most stunning is his report’s finding that lacking social connection increases risk of premature death by more than 60%.

The decline in social connection has been occurring over the past fifty years as a result of changes in family life, social infrastructure, technology, work, cultural norms, and the political environment. Effects of these changes are evident all around us. Still, it is shocking to read that only 16% of Americans feel very attached to their local community.

This country was founded on a series of compacts of mutual obligation by citizens to one another. The Declaration of Independence concludes with the words, “we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor.”

At times, it has required conflict, including a civil war, to expand our notion of who is a full-fledged member of that community of mutual obligation. And often it has been newcomers to our shores who have reminded us that the strength of our nation rests on our interdependence on one another.

Ephraim Urevbu was born in Nigeria. He grew up in the delta region of the Niger river, one of eight children raised by a single mother. Urevbu embraced art as a way to escape the bleakness of poverty and abuse from a step-father. Without the approval of his mother or step-father, he enrolled in Yaba College of Technology, majoring in art. Working as a stagehand for the International Festival of African Art and Culture, where he was assigned to the American delegation, expanded his view of what was possible. The following year he applied and was admitted to the Memphis College of Art.

In Memphis Urevbu encountered racism for the first time. Initially enraged, he chose to transform his anger through his work both as an artist and as a convener of civic engagement. He built a gallery and a restaurant around the corner from the National Civil Rights Museum located in the Lorraine Hotel, where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. had been assassinated. Urevbu’s Art Village Gallery serves both to promote emerging Black artists and to create opportunities for cross-cultural exchange.

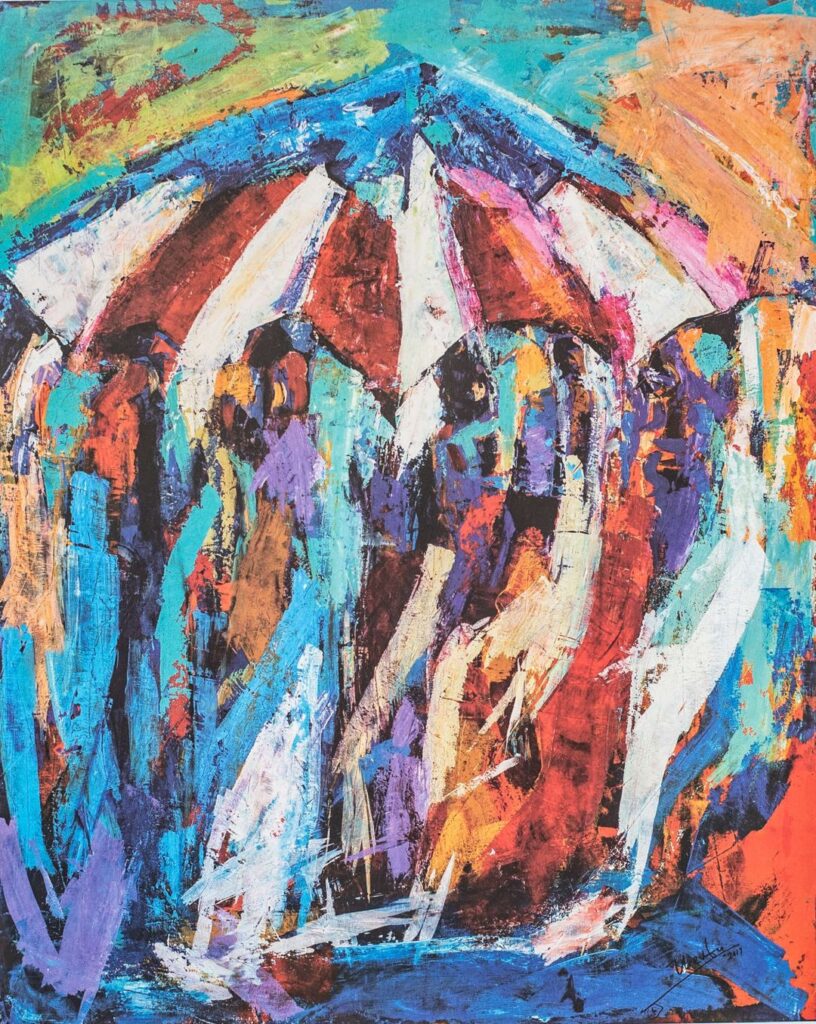

In 2018, as part of the MLK50 commemoration of the life and work of Dr. King, Urevbu painted the piece shown here, E Pluribus Unum. In describing the work, Urevbu said, “The American flag is prominently featured as an umbrella to which people of all nations, races, creeds, and dreams unite to build a nation so very powerful. The vibrant array of colors is a depiction of the diversity of nationalities who reside here and the many cultures and religions that make up what America is today. In a visual way I tried to capture the meaning of ‘out of many, one.’ If we celebrate that, focus on what makes us so strong, then we rise as a nation; then we fulfill Dr. King’s dream.”

Parsha Naso begins with a listing of the responsibilities of the various Levite clans for taking care of the Mishkan. The portion shifts to a description of the Sotah ritual, for a woman suspected by her husband of adultery. Following that is a recitation of the rules for a nazir, one who has chosen to live a stricter holy life than the rest of the community. Next is a special benediction, the Priestly Blessing, to be recited by the descendants of Aaron over the whole community. The portion concludes with a list of gifts each tribe is to bring to the Mishkan.

The Sotah ritual, addressing a matter of privacy between a husband and his wife, was discontinued by the early rabbis. The nazir was viewed skeptically by the rabbis, as one who effectively separated himself or herself from the regular customs of the community. It too was discontinued. The heightened responsibility of the descendants of Aaron for the community survived antiquity. The Priestly Blessing evolved into a form of chant and response between those of priestly lineage and the whole community, with that communal collaboration creating a form of divine hug.

Most enduring has been the value that the journey of freedom is sustained by communal obligation. Jewish life produced an extraordinary network of mutual benefit organizations and service agencies sustained by rich and poor alike. These have enabled communities to survive the darkest moments of oppression. It is a heritage that transmits the value that the true measure of freedom is the extent of our obligation to one another.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday June 1 as we explore the true measure of freedom.

Painting* E Pluribus Unum* by Ephraim Urevbu