The call of love draws us closer to one another. It’s always somewhat of a mystery, but it’s also the most realistic expression of what it means to be human.

View the study sheet here. Recording here.

In a week’s time the hunt will begin. On the evening before Passover it is customary to arm oneself with a candle, a feather, and a wooden spoon and to search every nook and cranny of one’s home for chametz (leaven). Every crumb is placed in a paper bag, and in the morning it is burned.

In the Hasidic tradition, chametz is not just grain that can rise. It also refers to one’s ego, our puffed up, overweening sense of self. To have a healthy ego is a good thing. It gives shape to our unique personality, motivates us to make a difference in the world and drives creative expression. But unchecked it enslaves our soul, twisting us into miserable and distorted beings…bearers of arrogance, indifference and cruelty.

This is how we begin our festival of liberation: by searching out and ridding ourselves of our dangerous sense of self-importance.

To be free involves making room for others. Opening the door of hospitality…even to the unfamiliar, the as-yet unmet…the stranger.

The Passover seder is designed to be not just the telling of an event that happened 3,000 years ago. It is an opportunity to enact freedom, right then…that very night. The evening begins familiarly enough. Candles are lit. A blessing is said over a cup of wine. Meal participants take an initial bite of vegetable. Then the elder breaks a matzah in half and recites: We are all slaves this year, next year may we be free.

Next year? There is a stirring among the younger ones around the table. The shattering of the festival’s most iconic symbol and the elder’s seeming acceptance of the current state of affairs unleashes a torrent of questions. Challenged, will the elder seek to reassert control and respond with answers that close down discussion or opt for a more open ended conversation? Will doors be opened, revealing the unexpected; or kept closed, to keep out the strange?

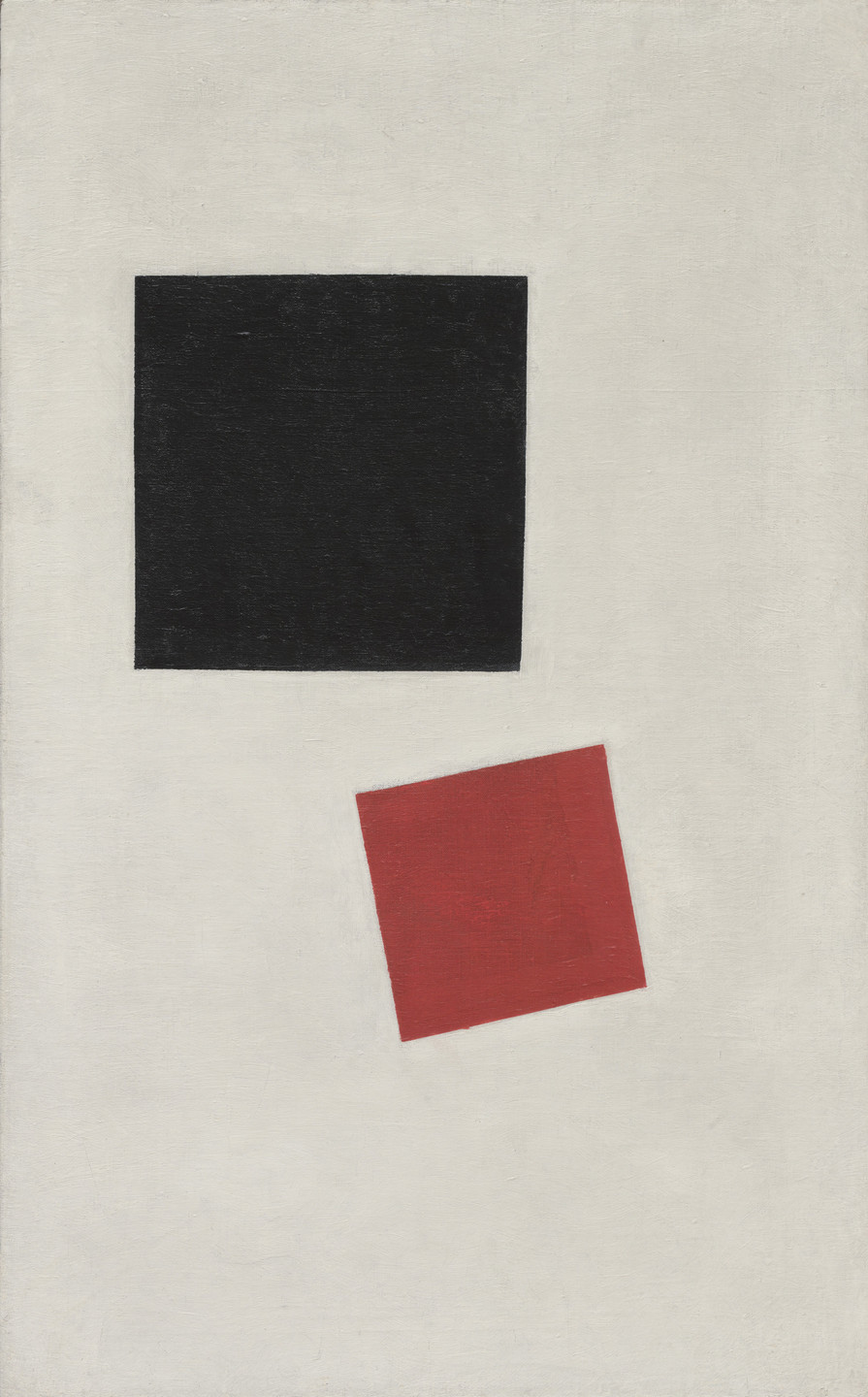

Kazimir Malevich was born in 1879 near Kyiv, Ukraine. He took up drawing as a young boy and attended art school in Kyiv and later in Moscow. By his early twenties he was immersed in the modernist movements of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism and Cubism. The horrors of World War I and the political stirrings in Russia produced in him an antagonism against bourgeois society and an openness to revolutionary change.

In the middle of World War I he innovated a radically new style of art, that of total abstraction. His works presented no recognizable figures or images. Color, form and space occupied his canvasses. He condemned representational painting as expressions of illusions, ones intended to impose a ruling group’s sense of reality on the less powerful.

In both his paintings and his writings he proposed a “new realism,” one that rejected the conventional understanding of realism as the representation of the world we see. He wrote, “Art no longer cares to serve the state and religion, it no longer wishes to illustrate the history of manners, it wants to have nothing further to do with the object.” To sever art from object was both a political and a spiritual release from control by others. It was to set both the body and the soul free.

Pictured here is his 1915 painting Painterly Realism of a Boy with a Knapsack – Color Masses in the Fourth Dimension. There is no boy. There is no knapsack. Just pure form, color, line, and space. For Malevich, objects are sources of limitation. “The artist’s goal,” he wrote, “is to achieve a blissful sense of liberating non-objectivity.”

The October Revolution of 1917 in Russia provided Malevich with a supportive context for his radically new approach to art. The Bolsheviks found his anti-materialist art useful as a cultural assault against the wealthy class. In 1918 he joined the People’s Commissariat of Enlightenment and was assigned several significant administrative and teaching positions.

By the 1920s, however, Soviet Russia had shifted from support of Malevich’s anti-representational non-objectivity to state-sponsored Socialist Realism. Art which did not representationally portray the achievements of the State was suppressed.

In 1930, Malevich was arrested and questioned about his political ideology. Two years later a state-sponsored exhibition commemorating the 15th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution was held in Moscow and Leningrad. Malevich’s paintings were included, but they were accompanied by labels identifying them as “degenerate” and anti-Soviet.

Barred from state schools and exhibition venues, Malevich retreated from his innovatively new style of art and turned back to older, more acceptable representations of peasant and landscape scenes and portraits of friends and family. He died in 1935 in Leningrad. His works were consigned to Soviet museum basements. It was not until 1988, under Gorbachev, that Malevich’s paintings were brought out and shown to the public once again.

At the height of his aesthetic fervor, Malevich wrote: “No more likenesses of reality, no idealistic images, nothing but a desert!”

For the Israelites the desert has been their site of freedom. Liberated from the oppressive weight of another civilization’s cultural materialism and system of human slavery, they have experienced what logic could not have imagined: a sea that parted; pillars of cloud and fire guiding their way; manna falling from the skies; quail that covered their camp; thunder that could be seen; and a Presence that could not be seen but was most profoundly and intimately known.

With Parshat Vayikra (“he called”), the Israelites leave behind that dimension of drama which has provided them with wondrous stories of freedom to tell their children, for generations and generations to come. They are the stories we tell at our seder. In Vayikra the Israelites cross over from the setting of Exodus to that of Leviticus, a realm almost without narrative, without the dynamics of human living. In its place is a recitation of sacrificial protocols and a description of one family’s ritual duties.

Instead of the nomadic movement of Exodus, there is a halt to the forward march by the Israelites. The national sharing of administrative duties and prophetic insights experienced in Exodus is displaced by a focus on a religious hierarchy which is to be one tribe’s inheritance. Is this some kind of return to Egypt, to a stratified society? Are rules, procedures and lists going to put an end to storytelling? Will the unexpectedness of wilderness be replaced with the precisely prescribed steps of sacrificial services?

Two words are used most frequently in Torah when referring to God. One is Elochim. The other is Adonai. The first is identified with God as distance and justice. The second is associated with God’s aspects of closeness, love and compassion. The word Elochim appears in the entire book of Leviticus only five times, and not once in the context of the people Israel. The word Adonai occurs 209 times in Leviticus. This is a book about love and intimacy. It may require more than a literal reading for us to sense that.

And it is a book about being called. The verb that launches this week’s portion, kara, evokes the very beginning of God’s closeness with humanity: “And God called out (kara) to the human…” (Genesis 3:9). Looking past the specific assignments given to Aaron and his sons, we see that back in the realm of Exodus, back at the moment when we stood at Mount Sinai amid the awe and wonder of it all, the Divine had proclaimed: “You shall be to Me a kingdom of priests and a holy (kadosh) nation.” Priestly and holy. All of us. Each one.

Calling. This is how angels address one another. Holiness. This is the nature they share with the Divine Presence. “And one angel would call (kara) to another, ‘Holy, holy, holy! (kadosh, kadosh, kadosh!) Adonai of hosts, presence fills all the earth!” (Isaiah 6:3). It is what we sing out as part of our Kedusha prayer, that moment of making contact most intensely with the Source of all life. As we chant this, we stand on our tiptoes, expressing our angel nature. And then we plant our feet firmly back on the ground, affirming where we are called to serve.

For a moment we experience Malevich’s goal for an artist: to achieve a blissful sense of liberating non-objectivity. And we understand a new realism: that of a call to love. It is what angels do. And it changes worlds.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) on Thursday April 3 as we explore a new realism: the call to love.

Oil on canvass Painterly Realism of a Boy with a Knapsack – Color Masses in the Fourth Dimension by Kazimir Malevich