When we give not in order to receive, we leave the weight of our fears behind and surpass what we thought we were capable of. We become extraordinary.

View the study sheet here. Recording here.

In a letter to his sister Sonia, the artist Mark Rothko wrote: “Here I am at the age of 40. I am on the brink of a new life. It is both exciting and sad, but I regret nothing about it. The last thing in the world I would wish would be to return to the old one.”

The number 40 signifies in Jewish tradition a transition from one state to another. Forty days and forty nights of the flood. Forty years to cross the desert. In ancient rabbinic thought, a human being achieved its form in the mother’s womb over a period of forty days. The rabbis taught that forty are the days between planting and harvest. Rabbinic tradition held that forty are the number of weeks between conception and birth. Forty is the time it takes for something to go from beginning to fruition.

Parshat Terumah opens with God instructing Moses to tell the Israelites to bring terumah (“gifts”) to God. Rabbi Chaim Ephraim of Sudilkov, the grandson of the founder of Hasidic Judaism, the Baal Shem Tov, observed that the word terumah, with its letters deconstructed and rearranged, consists of the word Torah plus the Hebrew letter Mem. The letter Mem has the numerical value of forty. Terumah thus means the “Torah of forty.” Terumah as the “Torah of forty” hints that what the Israelites are invited to bring transcends the mere materiality of the gold, silver, yarn, stones, oil, wood, and skins identified in the written text.

Humans, plantings and Torah share the same number describing their gestation, development and emergence into the world. There is a unity of all life. The Zen Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hahn in his book The Miracle of Mindfulness points to the pain and confusion caused by dividing reality into compartments. Aspects of reality do not exist as discrete things. They “inter-are.” He writes: “Interbeing; if you are a poet, you will see clearly that there is a cloud floating in this sheet of paper. Without a cloud, there will be no rain; without rain, the trees cannot grow; and without trees, we cannot make paper.”

The world the Israelites emerged from was one shaped by idolatry. In those societies people brought gifts to their gods as a transaction designed to obtain a material benefit for themselves. As part of the journey away from such a culture, Torah teaches a giving that does not anticipate a material receiving. It is an act designed to produce for the giver transcendence and a connection with the Source of all life, an “interbeingness.”

The word terumah is constructed from the Hebrew verb “to be exalted.” By freely surrendering something precious without expectation of a material benefit, the giver becomes uplifted, elevated. Eitan Fishbane, Professor of Jewish Thought at Jewish Theological Seminary, writes about the Hasidic understanding of giving without the motivation of receiving in return: “[It] is a process of transcending the prison of our own egotism and self-centeredness; in the moment of devotion we seek to break open the self-protective walls of our hearts, to make ourselves truly vulnerable to the indwelling of the divine presence…the divinity that dwells within, not only beyond the human.”

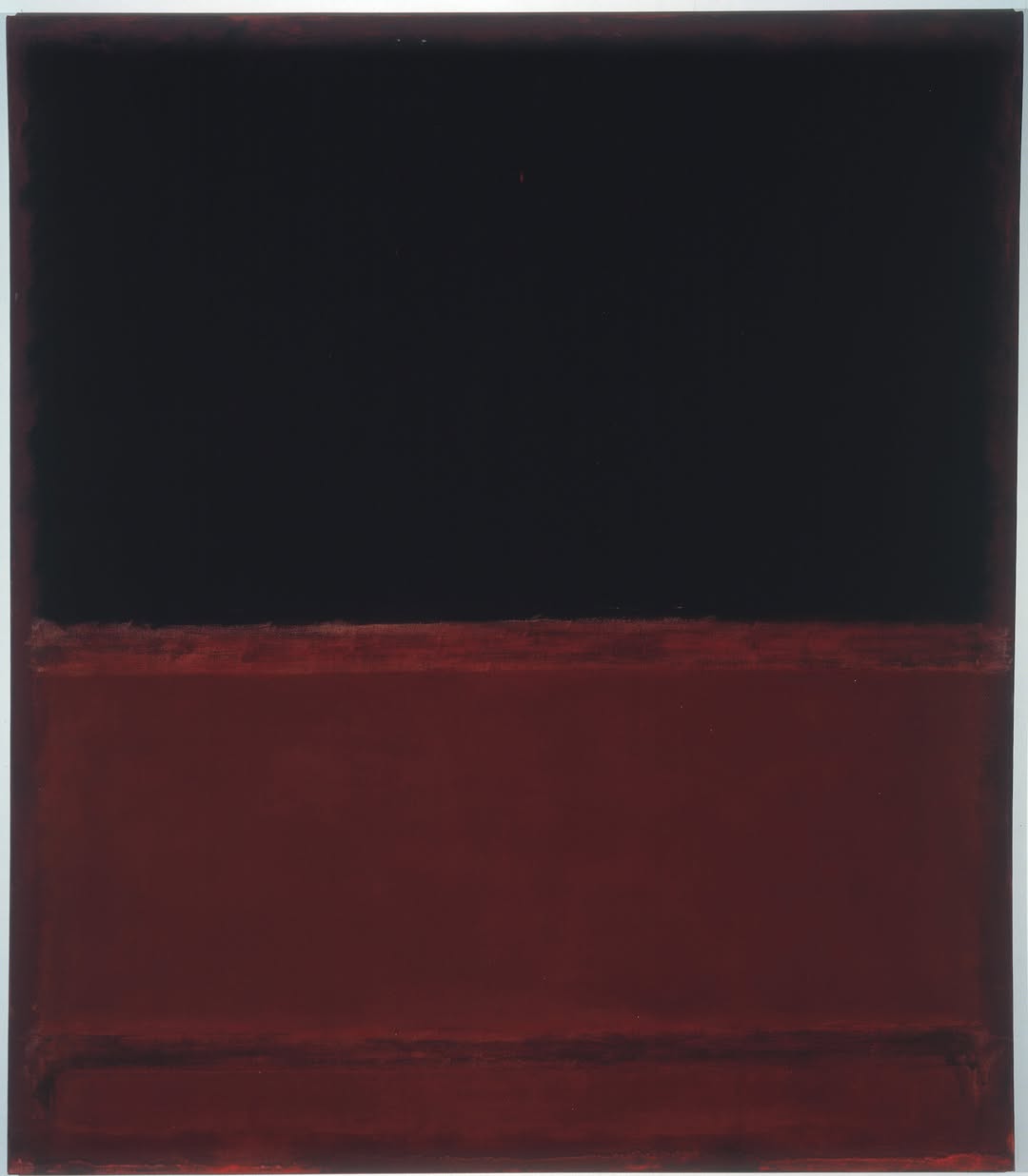

Mark Rothko achieved great critical and commercial success in the 1950s with his brilliantly colored paintings that appeared to viewers as sunny and joyous. Concerned at how superficial he felt that response to his work was, in the 1960s he turned to a darker palette. He wanted to create a more meditative experience, an opportunity for viewers to lose themselves in more subtle perceptual effects. To see nothing, to feel everything. There were not even any titles on these pieces. Cognitive clues were removed so as to not dictate intent or outcome to the viewers. All that offered itself to the viewer was…nothing and everything. Rothko wrote, “I don’t express myself in my paintings. I express my not-self.”

Pictured here is No. 22 from his darker palette series. A soft burgundy rectangle makes contact with blackness above it. Is this substance surrendering itself to Nothing? There is a point where below is about to meet above. That point of contact, where timeful encounters timeless, where the discrete touches the indefinable. T. S. Eliot experienced that in a walk through a garden in the Cotswolds and shared it with us in his poem “Burnt Norton”:

At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless/Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is/But neither arrest nor movement. And do not call it fixity/Where past and future are gathered. Neither movement from nor towards/Neither ascent nor decline. Except for the point, the still point/There would be no dance, and there is only the dance.

The Talmud promises that “in the merit of giving without expectation of anything in return [literally: the handing over of one’s soul] a person experiences miracles.” We leave the weight of our fears behind and surpass what we thought we were capable of. We discover interbeing. We become…extraordinary.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) on Thursday February 27 as we explore neither flesh nor fleshless.

Oil, acrylic and mixed media on canvass No. 22 by Mark Rothko