Life is found through the questions we ask and the creativity within us they unleash.

View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

A week ago we came to the end of a year. And what lay beyond it? Another year. This week we come to the end of a book of Torah, Genesis. And what lies beyond it. Another book. If only we could always be so reassured: that every ending would be followed by some new beginning.

Too many of life’s events defy our desire for reassurance. The death of loved one. A romantic breakup. A conflagration that destroys home and community. Financial collapse. Debilitating illness.

In the modern era, the elevation of rationality and science held out the promise that we could limitlessly expand our knowledge about all aspects of our lives and devise ways to minimize our vulnerability to randomness and loss. And if we could not prevent a loss, we could at least get closure over it.

Psychologist Arie Kruglanski coined the phrase “need for closure” over thirty years ago. He defined that as a desire for a firm answer to our perplexity and as an aversion to ambiguity. More recently, Pauline Boss, professor emeritus in the department of family social science at the University of Minnesota, wrote The Myth of Closure: Ambiguous Loss in a Time of Pandemic and Change, in which she challenges the pursuit of closure as a healthy response to loss.

Closure, she writes, conveys a sense of finality. It is an appropriate term to apply to the conclusion of a real estate deal or to the barricading of a road after a flood. But, she continues, it is a harmful concept to apply to how we should internally process the impact of loss in our lives.

A dear one dies, a home is destroyed, a career terminated. There may be finality to the dear one’s physical presence, to the home, to the career. But one’s attachment to any of those remains. And that attachment, and the pain that the absence may cause, is an important asset in one’s life. It is valuable, she writes, not to get over the loss but to live with it.

This week’s Torah portion narrates the deaths of Jacob and Joseph. Yet, it is titled Vayechi (“and he lived”). It calls to mind another portion which also describes a death, that of Sarah. It is titled Chayei Sarah (“the life of Sarah”). This insistence on seeing new life where biology’s limit would seem to focus us otherwise is the very nature of Torah language.

In the Talmud two rabbis are having dinner. One says, “You know, Jacob didn’t really die.” The other replies in astonishment, “What are you talking about? They embalmed, buried and eulogized him!” “Well,” says the first, “I’m interpreting a Biblical verse.”

This story of the power of interpretation to revive life, to overcome the plain, routine meaning of language, is included in the volume of Talmud about fasts, which focuses on fast days instituted in times of drought. Two rabbis in a volume about fasting are feasting. And the main course seems to be creative interpretation and its ability to bring life to that which seemed to be dead. Imaginative use of language sustains us more than adherence to a text’s literal meaning.

Lawrence Weiner, one of the central figures of Conceptual art, was born in 1942 in the Bronx. His parents ran a candy store. He graduated from high school at age 16 and left home to wander the country. He created his first art piece in 1960, “Cratering Piece,” which was an anti-sculpture formed by setting off a series of dynamite charges that notched unauthorized cavities in the field of a state park. That work characterized much about his future works: public, made with sparse means and no object left behind.

By 1968 words became a dominant feature of Weiner’s art. An exhibit in 1969 included a “Statement of Intent:” 1. The artist may construct the piece/2. The piece may be fabricated/3. The piece need not be built/Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the occasion of receivership.

Weiner’s declaration proclaims that there are several ways his work may be manifested, including not bringing the work to physical realization. And each one of these reflects the artist’s intent. He leaves the work open to the recipient’s free will and discretion. Weiner bestows upon the viewer co-status as creator.

What Weiner did insist on was the assumption of creative responsibility by the viewer. In an interview, he said: “When someone receives a piece of mine, assumes responsibility for the piece, they assume responsibility that this is art as well as I assume the responsibility.” The recipient must be one who as reader and interpreter makes a judgment and decision about the work. Weiner retained his agency over the piece’s initial realization while transferring to others its expanding meaning.

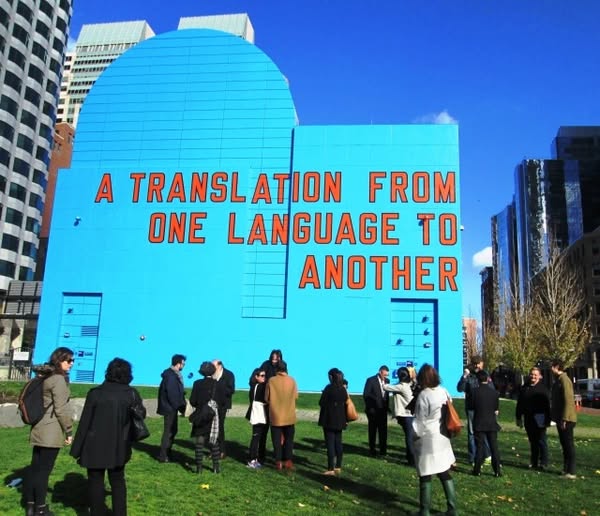

Pictured here is a mural he painted on a building at Boston’s Dewey Square Park. Seven large, bright orange words pop against an aqua blue background: A translation from one language to another. Weiner said, “Language is just another material – like oil paint, or spray paint, or stone, or chiseling into the building itself.” In the image shown here are people engaging the piece and one another. Each person viewing the mural has the potential to give it context and to share that with a person next to them. Every interpretation can be translated. Every translation of the work is an interpretation.

For Weiner the purpose of art is to ask questions. “The concept of being an artist,” he said, “is to be perplexed in public.” The reader of a work of art should equally be perplexed: “If you understand a work of art right away, it really has no use except as nostalgia,” he wrote.

The element of perplexity is what differentiates art from a report. The French philosopher Maurice Blanchot wrote, “Literature begins at the moment when literature becomes a question.” To dislodge words from their routine meaning creates a gap within which imagination can play. A reader who plays in that gap becomes a writer, one who, in Blanchot’s words, is “gripped by the infinite possibilities” of language and who “acts as the vector by which the new might enter the world.”

By its language, Torah invites us to see beyond the apparent. Where death seems to be obvious, there is life. By its very physical structure, Torah embodies the never-ending. It is not a book, It is a scroll, a megillah, from the Hebrew verb galal, to roll. That same verb gives us the word gilgul, reincarnation. There is no beginning. No end. There is a never-ending translation of infinite possibilities. And we are the artists who release them into the world.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) on Thursday January 9 as we explore the art of infinite possibilities.