Torah teaches us a song that is not finished. It invites us to be co-creators of this way of wisdom. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

The sculptor Jacque Lipschitz was once asked: “How do you know when a work of art is finished?” Lipschitz replied, “When I stop working on it.” One of Lipschitz’s final commissions was for a sculpture to be placed in front of Philadelphia’s Municipal Services Building as a work of public art. Due to political and budgetary infighting, Lipschitz’s plaster model sat at a foundry in Italy, waiting to be cast in bronze, when he died in 1973. That fall the Fairmount Park Art Association intervened and successfully had the piece, titled Government of the People, cast and installed in front of the building in time for celebration of the nation’s bicentennial. Sometimes it takes a community to bring a work of art into fulfillment.

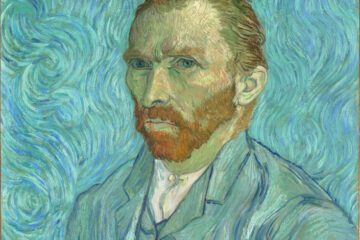

Joseph Mallord William Turner, one of the greatest English Romantic artists and landscape painters, was born at 21 Maiden Lane in London to Mary and William Turner, a barber and wig-maker, in 1775. Clearly a prodigy, Turner was accepted into the Royal Academy of Arts at the age of fourteen. The following year he had his first exhibit there, of watercolors. In 1796 the Royal Academy held an exhibition of his oil paintings.

Supported by a number of wealthy patrons but criticized by most art reviewers, Turner challenged a variety of social conventions. He refused to surrender his Cockney accent, which other artists did as a way to gain social acceptance and advance their careers. He remained a relative recluse, avoiding social gatherings. Most significantly, he defied the reigning standards of classical art. He increasingly focused on landscapes, which were considered less serious than works of portraiture, historical events or biblical scenes. And, unlike classical art, which valued balance, precision and representational accuracy, Turner unleashed on canvass the power of nature as he experienced it.

During his last few years of painting, Turner abandoned any pretense of representing objective phenomenon with recognizable precision. Many of his works foreshadowed a level of abstraction that would not be fully developed for another fifty years.

Pictured here is his work Rough Sea, painted sometime between 1840 and 1845, just a few years before his death in 1851. It is an unfinished painting. It presents very little in the way of identifiable detail. The dark form in the center could be a seawall or a harbor, but what is most pronounced is a sense of the power of the sea and the merging of water and air at the horizon line.

Unfinished painting, called non-finito, declines to fill in expected details. Entire areas of the canvass may even be empty of paint, allowing the blank white canvass to show. The effect can be an absence that speaks louder than any material presence. The power of non-finito to convey more than any amount of paint could became a prominent feature of Impressionist, Post-Impressionist and modern art in general. It presents a mystery which invites stories and interpretations. The viewer is enlisted in the work’s fulfillment.

In this week’s Torah portion, Nitzavim-Vayeilech, God summons Moses to “write this song” and to teach it to the people of Israel. What is “this song”? In the context of the narrative it appears to be verses Deuteronomy 32:1-43 (“Give ear, O heavens…”). However, a tradition within Talmud explains that the song referred to consists not just of those verses but all of Torah. And an even more radical interpretation is provided by another early rabbinic text which says that the song consist of both the written Torah and oral Torah.

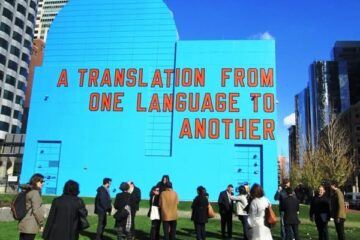

Oral Torah is an ongoing human elucidation of divine purpose. Its source is infinite and eternal. It defies complete and final capture by human language, which is finite and contextual. Drawing down fragments of divine purpose requires language that disturbs the settled, that releases words from their fixedness and restores the trembling experienced at Mount Sinai. We need words that have escaped “from the gravitational pull of finite meanings” (Rabbi Jonathan Sacks). In language, this is the function of poetry/song: “Poetry seeks to restore vibration to words whose life has become motionless” (Rabbi Marc-Alain Ouaknin, Mysteries of the Kabbalah).

In art, this revibrating role is served by unfinished paintings, non-finito, which reveal that both reality and we are also unfinished. There is more to discover. Lady Pauline Trevelyan was a contemporary of Turner. She was an artist and a hostess of one of England’s greatest salons for artists and writers. About Turner’s paintings she wrote: “You never get to the end of a picture of his. The more you look at it the more you find in it.” That is the way it is with art that is more discovery than message. “I have never started a poem yet,” Robert Frost said, “whose end I knew. Writing a poem is discovering.”

Torah teaches us a song that is not finished. We are its singers now, you and I. “Give ear, O heavens, and I shall speak! Let the earth hear the words of my mouth! May my discourse come down like the rain, my speech distill as the dew.” Our creativity restores vibration to that which has become motionless. Life is renewed.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) on Thursday September 26 as we explore unfinished work.