To build so that the divine might dwell here is an ongoing, dynamic process of redesigning ourselves and our world. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

The moment at Mount Sinai appears in Torah as a sympathetic resonance between nature and humankind. The mountain “trembles” and the people “tremble.” For the first time, the power that is the Source of all life cracks through vibrational buffers and is accessible to be heard by everyone. So profound is the irruption that it produces a jumbling of senses. Sounds are seen. Images are heard.

The Torah itself seems to bear the effects of this upending of logical order. The medieval commentator Rashi points out that verses in Exodus chapter 24 which look as if they are describing events occurring after the moment at Mount Sinai are out of order. They are actually narrating a moment that took place three days before. Humans, nature and the annals of time shudder sympathetically as the old order of things is overturned.

I think of that shared response among humans, nature and the annals of time to shifts in existence when I read about dramatic alterations in the life of our planet: extreme weather events; volcanic eruptions; warping of the earth’s crust as glacial ice melts. Humans are experiencing dramatic shifts as well: issues of social and personal identity; national borders; the nature of work; education; access to and the power of information. Art, as an annal of time, bears witness to these various fracturings and recompositions.

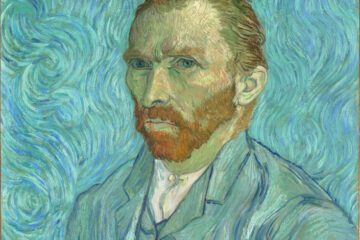

Our moment, of course, is not the first to have experienced dramatic alterations in either human or natural existence. The end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries was a time of profound transformation. The industrial revolution radically altered the human experience of time and community. Populations shifted from countryside to city. Coal mines displaced agrarian fields. Black soot blotted out once clear skies. Aristocracy declined to almost irrelevance as the middle class ascended to a place of preeminence. Empires collapsed. New nations arose. Mechanized warfare reshaped battlefields.

In that very moment there arose, if ever so briefly, a group of artists declaring their intent to sweep away all cultural expressions of the old order. Based primarily in Italy during the period 1910 to about 1930, the Futurists denounced as retrogressive traditional artistic standards, remnants of an aristocratic and anti-popular regime. They glorified everything modern: industry; mechanization; and, above all, speed and motion.

Umberto Boccioni was one of the most influential Futurists. His encounter with Cubism inspired him to exploit even further the dynamic facets of reality disclosed by that style. Boccioni believed that scientific advances and the experience of modernity demanded that the artist abandon the tradition of depicting static, legible objects. The challenge was to represent movement, the experience of flux, and the inter-penetration of objects.

In 1910 Boccioni published Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting. In it he wrote, “Our growing need of truth is no longer satisfied with Form and Color as they have been understood hitherto. The gesture which we would reproduce on canvass shall no longer be a fixed moment in universal dynamism. It shall simply be dynamic sensation itself. Indeed, all things move, all things run, all things are rapidly changing.”

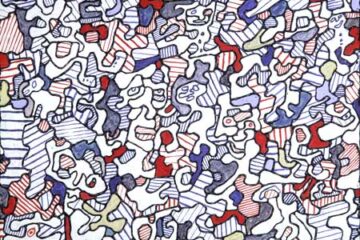

Norman Gorbaty grew up in Brooklyn, the son of Eastern European immigrants. Yiddish was both the language and the culture of home. He studied at Yale with painter Joseph Albers, who initiated him into art as magic-making, and with architect Louis Kahn, who taught him that bricks could talk and guide an architect. He spent much of his career as a graphic artist in the advertising world. Still, every night he would repair to his studio at home and create paintings, pastel works and sculptures.

Gorbaty felt great kinship with the Italian Futurists. Like them, he infused his canvasses with dynamic motion, disruption of the static and a collapsing of time and space. He said that he didn’t “make” a picture. He “did” a picture. I was fortunate to meet and interview him in 2016. In response to my question about what it meant to “do” a painting, he said: “It’s about movement. I am fascinated by the motion around us and try to capture that in my work. There is movement in life as we ‘do’ it. Everything moves. Images are constantly in motion. It is the doing of the work that I am about.”

Pictured here is his pastel work Torah. A swirling vortex of energy, emanating perhaps from the tallitot (prayer shawls) embracing the Torah, sweeps through and around the sacred scroll. Perhaps the pulsations are those of the tallitot wearers, who are spinning so fast that we cannot even see them. A reciprocal vibration is generated within the Torah itself. Is that one Torah or many in the image? Is there perhaps only one person praying or are there many? Is each, Torah and the one praying, being birthed into a multiplicity of dimensions of themselves by the other? So much motion. So many possibilities.

The Israelites are called upon in Parshat Terumah to memorialize the shift from Egypt to promised land by engaging in a building project. In Egypt they were forced to build monuments that championed the quest for immortality, proclaimed Pharaoh’s absolute power over everyone, and glorified the subjugation of human labor. Would the form and design and purpose of the new structure reflect anything other than a change in sovereigns?

The Hebrew emphasizes that it is not the physical structure itself that is the site of divine dwelling. The “doing” of the work will cause God to dwell, not in it, but in “them,” the people. And this dwelling is not a static event. A Hasidic commentary highlights a shift in pronouns in God’s instructions: “They shall make Me a sanctuary…and so shall you make it.” The commentary observes: “Moses and his generation conceived of the sanctuary by their own light, their own vision. ‘And so shall you make it’ means you shall make God’s sanctuary according to the visions of your own time and place.”

We have the capacity to disrupt the static and to build structures that honor and sustain human existence and an all too fragile planet. Generations before us have been so summoned, and now we are: to shape according to our own light and our own vision a world that will cause the divine to dwell within us.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday February 15 as we explore and so shall you make it.