At the heart of building a sacred community is weaving work, the interlacing of different dimensions: both between oneself and the world and within one’s own self. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

The longest thematically driven narrative in Torah is that devoted to the building of the Mishkan and its vessels. It consists of fifteen chapters and is the concluding focus of the book of Exodus. The Mishkan is a construction project. Yet, what exactly is being built?

On a trip to Israel’s Timna Park, a desert area located about 20 miles from the Red Sea, I came across a replica of the Mishkan built by a church group. It was painstakingly constructed according to every dimension and color detailed in the Torah. The altar, the table of showbread, the ark of the covenant, the lampstand, the priestly garments: all were there. It was a vacant and lonely place.

In the Torah the Mishkan is described as a building project designed to induce a meeting, a drawing together of the eternal and the transitory. It is not the material structure itself that achieves that communion. It is the active process of constructing, conducted with the intent of sacred elicitation and elucidation, that draws together seemingly separate dimensions.

The most essential element of the Mishkan in the Torah’s description is space. “Make Me a set-asideness [mikdash] and I will dwell in the midstness of the people.” “I will meet with you in the space between the two cherubim.” The function of this space is to enable the Israelites to bring wholeness into their lives. “There is in all visible things,” the Trappist monk Thomas Merton wrote, “a hidden wholeness.” In his book A Hidden Wholeness: The Journey Toward An Undivided Life, educator Parker Palmer advises that “we create spaces between us where the soul feels safe enough to show up and make its claim in our lives.”

The most critical building material in the creation of such sacred, healing space is imagination. Gaston Bachelard, author of The Poetics of Space, writes about the role of imagination in designing space shaped not in response to our fears but in furtherance of our relationships with others. To imagine beyond the static present is the work of artists. The Hebrew word for artist is oman. It is built upon the same root letters as amen, an expression of affirmation, and emunah, faithfulness.

One of the specific items prescribed for the Mishkan is a parochet, a curtain, to separate the Holy of Holies where the Ark of Testimony was kept and the Holy area that is the rest of the Mishkan. The medieval commentator Rashi describes the parochet as the work of an artist: “This is weaving work, not embroidery,” he writes. It is a piece that interlaces together different images, different threads, to create a whole fabric.

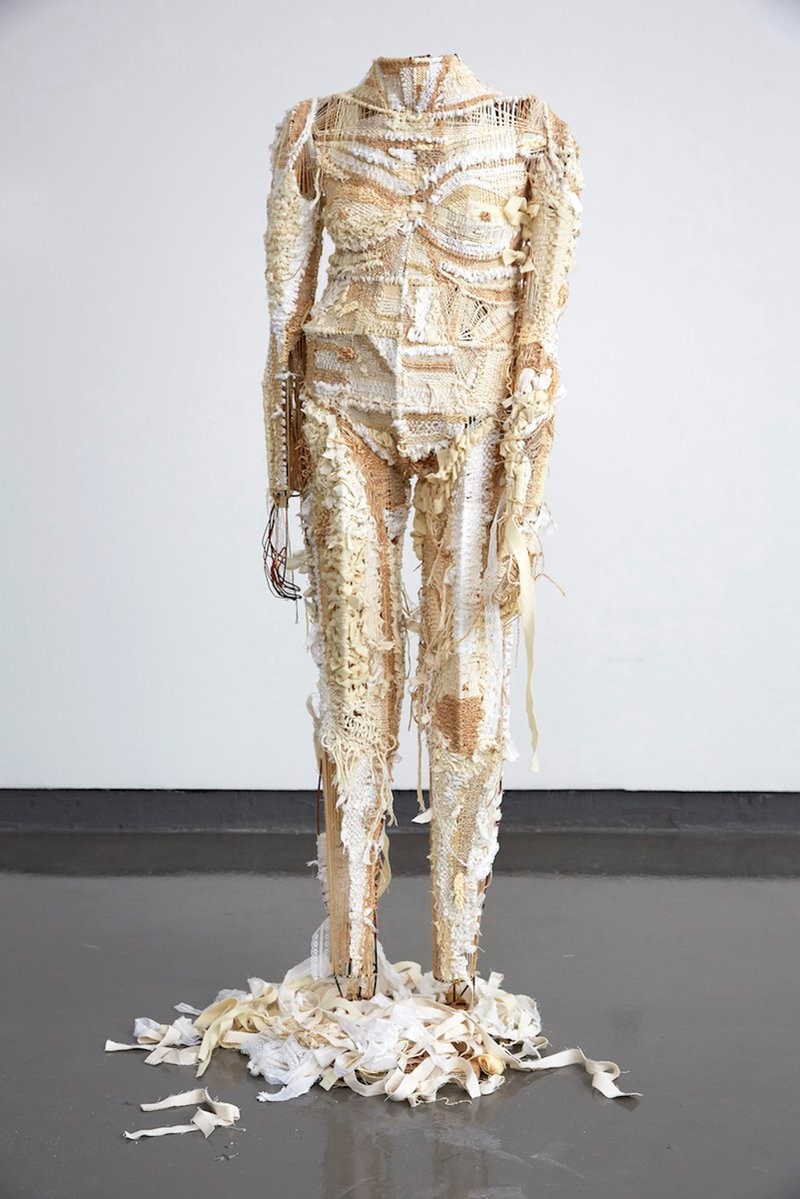

Jess Self is an artist from Black Mountain, North Carolina. She incorporates wax, wool, wood, and textiles into sculptures made from her own life body casts. Inspired by Buddhist teachings and the psychoanalytic writings of Carl Jung, she uses body casts of herself in combination with the other materials to facilitate an exploration of her own life and to create a connection between individual identity and universal existence. Pictured here is her piece Wholeness.

Over a cast of her own body, Self has draped a woven piece. “This figure,” she writes, “has experienced every mood, the ups and the downs, the tears and joy, which is embedded in each section of her woven skin.” The articulation of her own multiple dimensions becomes a pathway for connecting with that which is beyond her singular self, with the expanse that is the universe.

The poet of psalms honors this sacred weaving work: You formed my inmost being/You wove me together in my mother’s womb/I praise You/For I am awesomely and wondrously made/Your work is wondrous/My soul knows this well. (Psalm 139:13-14)

Join us as we explore weaving work, the interlacing of multiple dimensions into a whole fabric. It is a work that deep down we know well.