To overcome the need to avoid the inevitable fissures in life, to let go of the desire for complete control is the beginning of freedom, fulfillment and responsibility. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

In just a few weeks’ time we will celebrate Passover, the monumental story of the Jewish people that brings us all to the table. Whether we are traditional or modern, conservative or liberal, believers or non, we are drawn to the meal’s gathering to retell the story that has given shape to us as a people and as individuals.

The evening begins familiarly enough: lighting candles, blessing children, blessing wine, washing hands, and then….In place of saying a blessing over challah, we break a matzah in half. That breaking of the holiday’s most iconic symbol creates a fissure in the familiar. Children erupt with a series of questions. Those are responded to less by direct answers than by a communal telling of a story, with all of its creative diversions and detours those around the table are inclined to take.

From that moment on the way of children shapes the evening’s discourse. Questions, story and song displace any frontal instruction. Children also control the evening’s conclusion. The seder cannot end until the afikomen is found, until a child brings to the table the hidden half of the broken matzah and restores it to the one held by an adult. The fracturing of the familiar has the curious outcome of reaffirming tradition.

Robert Motherwell was one of the founders of Abstract Expressionism. His work reflected two key elements of that movement: that what appeared on the canvass was not preplanned but a record of an internal experience; and that painting could serve a spiritual, transcendent purpose.

Critical for Motherwell was the need to separate from pre-conceptions and formulas. “It’s essential,” he wrote, “to fracture influences, in the same way that free association in psychoanalysis helps to fracture one’s social deceptions.” Equally important was setting aside any certainty of outcome before setting brush to canvass: “Any art is academic by definition if you know what the result is going to be before you start.”

Motherwell embraced “an art that refused to spell everything out.” For him there were no concrete answers, only questions, discussion and debate. To paint, he said, is to be in “a state of anxiety that is obliquely recorded in the inner tension of the finished canvass.”

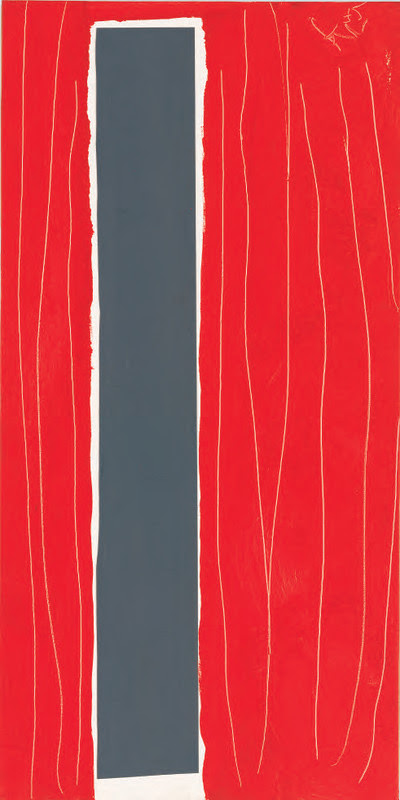

Pictured here is his work Untitled (Red, Grey). It is a collage of paint and paper. There is a simplicity in its form and colors: a grey rectangle housed in a larger red rectangle. The grey speaks of dull coolness, the red of urgent passion. Trimmed between the two is white paper that he has cut and pasted onto the board. There are incisions in the red.

I make no assumptions about what it manifested for Motherwell. Looking at it now, I see a structure. A doorway perhaps. It causes me to think of Passover. The doorways of the Israelites. The lintel. Blood upon the doorposts. So much blood. The grey speaks of shadows, of darkness. I think the Israelites carried some of that with them, even in their liberation. I think we all do, even in ours.

The book of Leviticus introduced itself as the most formulaic and least narrative-driven of any of Torah’s books. A manual for the priests on how to conduct a series of prescribed rites, rituals of certainty. The momentousness of the very first offering is immediately overshadowed by the horror of two of Aaron’s sons being consumed by divine fire for the trespass of impetuously bringing an offering that had not been prescribed.

It is an event that provokes more than a thousand years of questions: Was such punishment justified? Why did the two sons do what they did? Why did Aaron remain silent immediately following the tragedy? A text that opened as a source of detailed clarity and explanation transforms into one of deepest mystery.

Is this text we call Torah primarily one of certainty or doubt; command or question; oration or silence; continuity or fragmentation?

Another artist who explored beyond the boundaries of the conventional was poet Allen Ginsberg. He died on the Shabbat in 1997 when the Jewish world was reading Parshat Shemini. In his poem “This Is About Death” he wrote: Art recalls the memory/of his true existence/to whoever has forgotten/that Being is the one thing/all the universe shouts/Only return of thought to/Its source will complete thought/Only return of activity/To its source will complete/Activity. Listen to that.

Ginsberg sees beyond what has been tamed and brought under control as a noun, a well-defined and static object. He reminds us that the source of all is dynamic, a verb: Being, Activity. That is what “all the universe shouts.”

Passover is a time for poetry and imagination and the fracturing of unquestioned certitude. During the seder we ask a child to open the door to the unknown. Can we ask any less of ourselves?

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) on Thursday April 4 as we explore listen to that.