Open works of art engage us as participants in and not mere observers of creativity. To live that way lies at the heart of building community. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

In just a few days we will celebrate New Year’s Eve. Fireworks, the blowing of horns, the banging of pots and pans announce a consequential time that has come. The end of an old year and the beginning of a new one. Even as we sing Robert Burns’ poem Auld Lang Syne as a toast to old friendships, our gaze is oriented forwards. We welcome the closure that the calendar’s definition provides us to file away what has been, with all of its short-comings and difficulties, and to embrace the opportunity for a fresh start.

Social psychologist Arie Kruglanski coined in the 1990’s the phrase “need for closure,” which he defined as an individual’s desire for a firm answer to a question and an aversion toward ambiguity. While decision making is an important element in one’s life, Dr. Kruglanski’s studies focus on the extent to which we, especially in times of extreme polarization and crisis, trick our minds into thinking that we have enough information: “If we convince ourselves that we’ve solved the problem, we don’t have to wonder anymore.”

Dr. Kruglanski is no stranger to crisis and polarization. He was born in 1939 in Lodz, Poland. His family, at first confined to a Jewish ghetto, survived the Holocaust and later settled in Israel. He is presently on the faculty at the University of Maryland, where he directs a lab that studies human motivation as it affects thinking, feeling and behavior.

Our constant need to make decisions hardwires us, Dr. Kruglanski observes, to avoid ambiguity and to embrace radical certainty. It requires active intervention on our part to disrupt that natural tendency, to remain open both to additional information and to what we are capable of becoming.

The book of Genesis is bookended by lessons that confound our sense of certainty. The first portion, B’reishit, upends our notion of what a beginning is. By starting with the second letter in the Hebrew alphabet, it hints that there is another, prior beginning. And the very first word violates the rules of Hebrew grammar by being followed by a verb instead of by a noun, which its form dictates it should have been. The great medieval commentator Rashi confirms our growing bewilderment: “These verses are not about the order of Creation!” What then are they about? We are set on a course of wondering.

As much as B’reishit confounds our expectations of what a beginning is, the final portion of Genesis, Vayechi, challenges our notion of what a closing is. Torah’s scribal rules require that there be a space of at least nine letters between the end of one portion and the start of another. Yet, here there is a space of only one between Vayechi and the preceding portion. The narrative climax revolves around the death of Jacob. Death, surely a moment of finality. Yet, the text does not say in Hebrew that Jacob “died,” as it did in describing the passing of Abraham, Sarah and Isaac, only that he “expired.” Did he die or not? There’s a debate about that in the Talmud.

And on his deathbed Jacob announces to his sons that he is going to tell them what will happen in the “end of days.” But instead of an eschatological discourse describing how the world will end, Jacob detours to a survey of his sons’ individual qualities. Rashi observes this abrupt shift. Jacob seems to recognize that a radical disambiguation of the future would rob his children of their will to choose. They will have to live in the wilderness that life is, with all of its absurdity and pain and without the intoxication provided by a vision of assured resolution. He pulls himself and his children back from the brink of radical certainty, from that dimension where narrative comes to a final end, and draws them back into the story, one that it will be their responsibility to continue writing.

This continuation of writing lies at the very heart of Torah. Literature which guides a reader to a predetermined conclusion is a form of closed composition. That which draws readers into a plot as participants in the drama is a form of open composition. The Jewish Bible ends as a cliffhanger. The king of Persia challenges Jews living in exile to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple. Beyond the written book, Torah’s story and purpose continues in the form of oral tradition as embodied in Talmud, midrash and the sacred imaginings of kabbalah and more.

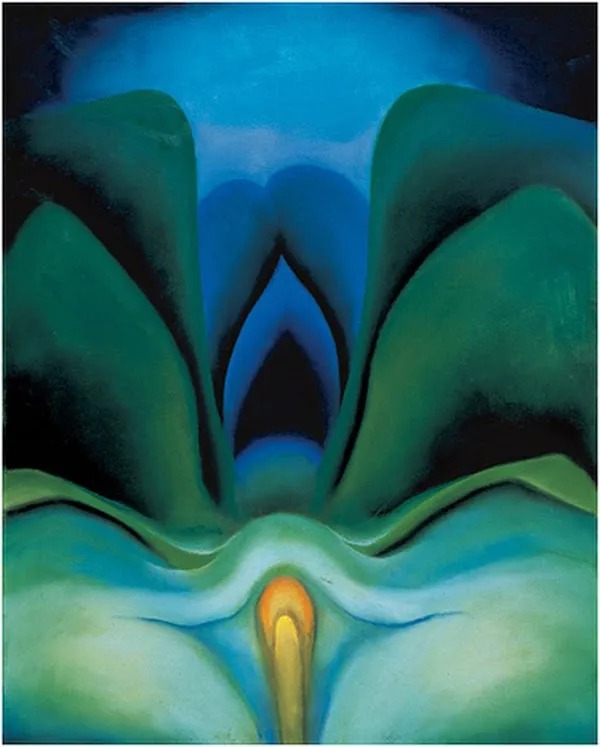

Open composition can also be expressed in two dimensional art. Paintings that have shapes running off the edges and sides of the canvass create a sense that the work extends beyond the edges or boundaries of the picture. This allows both for more active eye movement and for greater imagination by the viewer: What is happening off the canvass? Whereas verticals and horizontals can suggest inactivity, organic shapes promote a sense of flow. And in contrast to the tendency of vertical and horizontal lines to lead the eye off the canvass without a way to re-engage into the composition, rounded shapes allow the eye to come back into the picture.

One of the greatest artists of open composition in the 20th century was Georgia O’Keeffe. Born in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin in 1887, she moved to New York City at the age of twenty to study at the Art Students League. She soon became attached to Alfred Stieglitz’s Gallery 291, one of the few places in the United States where European avant-garde art was exhibited.

O’Keeffe was deeply influenced not only by the photographyof Stieglitz but also by that of Paul Strand and by the commercial photography and precisionist paintings of Charles Sheeler. She was fascinated with the camera’s ability to serve as a magnifying lens. Early in her career she began making large-scale paintings of natural forms at close range. The result was a body of abstractions decades before that became the dominant style.

Pictured here is her Blue Flower, painted in 1918. The voluptuous forms undulate across, up, off and back onto the canvass. Rich colors bleed into one another. Is this a flower shown at a hyper-magnified level of reality? Or is it flower-as-procreative-intimacy abstracted into pure sensuality? O’Keeffe’s power, and probably her intention, is to zoom us in and out, back and forth between hyper-realism and hyper-abstraction.

O’Keeffe once observed, “Nothing is less real than realism.” If that is the case, then what is “more real”? Could it be what lies in our imaginations, waiting to be awakened by moments demanding our acts of human choice and responsibility? If so, then we need more writers, more artists, more communal leaders inspiring us with open compositions that stimulate our own creative contributions to the human narrative.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday, December 28 as we explore an open composition.