We can enrobe words with different ones (metaphors). We can enrobe ourselves in different personas. These open up different possibilities, new ways of seeing what we thought we knew. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

It all began with a dream. Jacob steps across the threshold of his parent’s home onto a path for his own future. And immediately he has a dream. There are angels, a ladder and…God. A voice reassures him: “I am with you. I will protect you. I will make sure the promise of a rich and expansive life is fulfilled for you.” The text records no rules being given to Jacob, no requirements, no instructions about what to do next. Maybe he just forgot them upon his awakening. Or maybe not having them was in fact the guidance.

Why does Torah begin with the story of the creation of the entire world? Why not start with the first commandment that God gave: “This month shall be for you the beginning of the months” (Exodus 12:2)? That is the question the medieval commentator Rashi asks at the very opening of Torah. His answer is that it was to teach us as a first lesson that the whole earth belongs not to any particular nation but to God.

There is also this: It introduces Torah not primarily as a book of law but as a book of story. In doing so, it highlights responsibility rather than authority. Millenia later we have an Irish poet, William Butler Yeats, and a Jewish poet, Delmore Schwartz, each share with us the wisdom: “In dreams begin responsibility.” In Schwartz’s case, it is the title of a short story of a young man who dreams he is in an old-fashioned movie theater. He becomes aware that the movie is about his own parents’ life. Disturbed by what he sees and discontented to be merely a viewer, he becomes an active participant, yelling at the screen, attempting to influence his parents’ actions. An usher tosses him out of the theater and tells him he will be sorry if “he doesn’t do what he should do.” The young man wakes up. It is the morning of his 21st birthday. It is the end of something. It could be a beginning.

The whole Jewish Bible is a saga of journeying. Of settlements and dis-settlements. Of homecomings and exiles. Of self-recognitions and self-estrangements. This whole body of narrative wisdom presents itself to us not as report or lesson but as story so that we might become participants in it…as if it is the story of our own life. Because it is.

Metaphor is a key literary device. It serves both to disrupt and to fuse understandings, by disrobing objects of their familiar meanings and dressing them with new ones borrowed perhaps from a chest in the attic of our experiences. Activating our imagination, metaphor conjures. Images and feelings from other settings find new attachments. It recruits us to be co-creators not only of the life on the page before us but also of the life that is us. We are dressers creating meaning.

This week’s Torah portion has three instances of characters wearing garments that propel forward the narrative. Joseph wears a striped coat intended to signify the special place he holds in the heart of his father, above that of his older brothers. Tamar puts on the garments of a prostitute in order to seek justice from her father-in-law Judah. And Potiphar’s wife seizes Joseph’s garment in order to use it in a scheme to prove that he had raped her.

In the story-line of the portion, each of these garments has a physical dimension. But they also speak of different positions of power and how we relate to others. The father blind to the impact of the differential display of love among his children. The son oblivious to the pain and anger provoked by his position of privilege. The widow, diminished in power within a patriarchal world, needing to dissemble in order to gain justice. And the wealthy woman of privilege wielding in her hands the power of life and death over those who serve her. Torah whispers: You have this enrobing power too. How will you use it? For selfish love? For power? For justice? To hide, or to reveal?

One of the greatest self-image manufacturers among artists in the 20th century was Salvador Dali. Not content to merely let his artwork speak for itself, Dali enrobed himself in ways intended to promote both himself and his artistic vision. His extravagant and histrionic mustache may have been his most famous feature, but he dressed and coifed himself to extend his art beyond the canvass. He was very self-conscious in how he presented himself.

Dali primarily expressed his art through Surrealism, a movement that explored the unconscious, the non-rational, the realm of dreams. The Surrealist artist encounters and gives expression to unexpected juxtapositions, distortions of the familiar. Dali was a consummate Surrealist painter, describing known objects in unfamiliar form and in strange contexts. His painting The Persistence of Memory is a prime example of presenting identifiable objects in ways alien that cause us to rethink what we thought we knew about them.

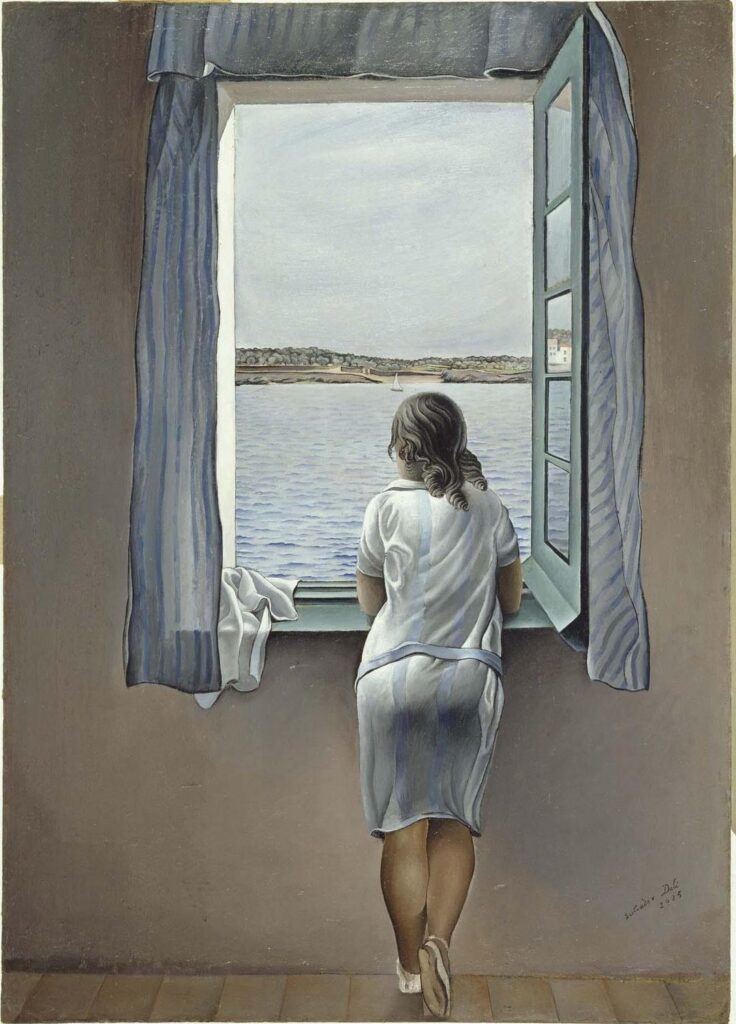

The painting here, Figure at the Window, confounds our expectation of Dali the Surrealist. It is representational rather than surrealistic. It is almost as if he is channeling a younger and very different artist, Andrew Wyeth. There is a serenity, if also a loneliness. A chaste figure gazes with longing upon an expanse beyond the confines of her world. Compassion, pathos displace Dali’s usual sense of irony and mockery of the ordinary. What might have compelled Dali to don the persona of a Wyeth? Who is this figure that evokes a different sense of self from him? It is his sister Ana Maria.

Whatever tenderness Dali felt toward his sister that caused him to wear the affect of a representational painter evaporated within decades. Ana Maria wrote a memoir in 1949 entitled Salvador Dali As Seen By His Sister which enraged Dali with its portrayal of his childhood that was completely at odds with his own description of a troubled childhood and of a life of torment at the hands of their father.

In response, Dali discarded the Wyeth affect of pathos and compassion and redressed in the Surrealist’s contempt for the normal and the benign. In 1954 he painted Young Virgin Auto-Sodomized By The Horns Of Her Own Chastity. It is a savage, Surrealistic piece, in which the figure by the window is now assaulted and decomposed by phallic forms. Thirty years of non-contact between them followed, until 1984 when Ana Maria visited Dali in the hospital, at what was thought to be his death bed. Dali yelled abuse at her and had her tossed out of the room. They never saw one another again. Dali died five years later, and Ana Maria died five months after him.

Donning a cloak, whether of the material or the psychological dimension, allows us to experience the familiar in unfamiliar ways. We can expand our perceptions and enlarge our sense of empathy. One of the great masters of the use of metaphor in our times was the Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai. He would walk the streets scanning everything and replay it all for us with a language that caused us to see it so startingly fresh. I am and ever shall be grateful to my teacher Rabbi Bill Cutter for introducing me to Amichai through his reading of him both as a writer and as a living human being.

In his volume Open Closed Open Amichai visits familiar moments and places: the Holocaust, Israel, Jerusalem, and the Bible. We meet them all as if for the first time. The poem “The Bible and You, the Bible and You, and Other Midrashim” contains these verses:

As the Torah scroll is read aloud each year

from “In the beginning” to “This is the blessing”

and back to the start, so we two roll together

and every year our love gets a new reading.

Here the image is of Torah and reader as being lovers who roll together, who roll over one another. It evokes an exchanging of positions, with roles of dominance and submission, of giving and receiving being shared back and forth. Amichai’s animation of Torah into a sentient being gives a whole new reading to the Mishna’s exhortation “Turn it, and turn it, for everything is in it. Reflect on it and grow old and gray with it.” The turning now becomes a physical, sensuous examination of all you and your partner have to offer one another in all ways.

In our rolling we return to the beginning and Rashi’s exclamation at the opening verse of Torah: “It says expound me, explore me!” What is most clear from the Torah’s first words is that language is unstable. The first word itself is a grammatical oddity, and all of Torah is written without vowels and without punctuation. Meaning is not fixed. It depends on context, and that is our task not God’s. Torah’s narrative winking seems to imply, “Authority is important but responsibility is critical.” Enrobe the language, and yourself, in something new and see what you bring to life.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday December 15 as we explore the uses of a cloak.