Breaking continuity can sometimes be the best way to maintain it. View the study sheet here. Watch the Zoom recording here.

New Year’s Eve tempts us with two illusions. One is that the past year is over and can be relegated to mere memory. The other is that the new year is the bearer of fresh starts and new possibilities. The opposite can actually be said of each. The past is ever with us in our shaping of the future, and a new year can result in a mere replication of the old.

The dramatic re-encounter of Joseph and his brothers after years that included betrayal, violence, and lies reaches its climax in this week’s Torah portion. Joseph has made himself unrecognizably alien to his brothers and has thus far refused to discard his Egyptian dress, language or name to make himself known to them. Yet, he does not appear to be able to just let go of them. His act of estrangement seems motivated by a desire to weave a new fabric of family life. But to become a source of healing this break requires that choices be made by all involved.

Not knowing that it is Joseph before whom he appears as an accused spy and thief along with his brothers, Judah steps forward and pleads for the life of their youngest brother, Benjamin. He offers himself as a slave in place of Benjamin. Judah has had his own moments of shattering reckoning: the death of two sons and the revelatory lesson about justice taught by his daughter-in-law Tamar, herself disguised so that she might bring Judah back to the path of tradition and its ethics.

Having been twice called forward to rehabilitation by family members in estranged garb, Judah cracks open his heart and offers his life in servitude to the power that is Egypt. In response, alien Egypt dissolves and reveals itself to be the familiar, the familial…his brother. And all embrace and weep in their reunion. Estrangement has served as a pathway to a new unity.

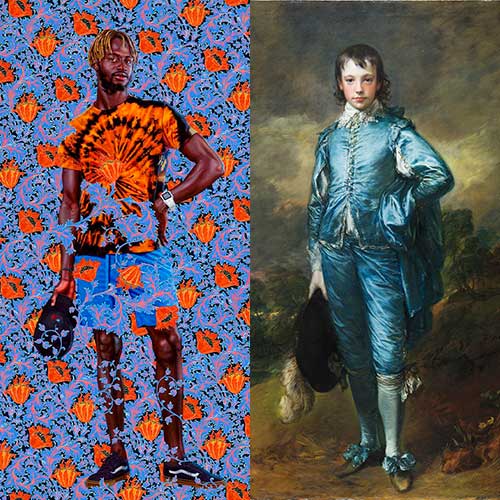

In 1770 Thomas Gainsborough painted what has become one of the most iconic portraits, The Blue Boy. It is at once an homage to the past and an upstart declaration about the future. The subject seems to have been inspired by a painting done in 1640 by Anthony Van Dyck, Portrait of Charles Stanley, Lord Strange. By the time Gainsborough painted his work, the garment worn by his subject was a century outdated.

This harkening back to another era by subject was enrobed in a palette that proclaimed a break with the aesthetic standards of the day. No less an authority than Sir Joshua Reynolds, a rival portraitist of Gainsborough’s and President of the Royal Academy of Arts, had stated that paintings should always contain warm, mellow colors of yellows and reds. Colder colors such as blue, grey and green should be used only sparingly. In brash opposition, The Blue Boy proclaimed its presence with a dominating cool Prussian blue.

American railroad tycoon Henry Edwards Huntington purchased The Blue Boy in 1921 and had it installed at what is now the Huntington Museum of Art. To commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of that purchase, the Huntington Museum commissioned artist Kehinde Wiley to respond to it with a work of his own.

Wiley, who grew up absorbing the classic art on display at the Huntington, became an artist firmly situated within the tradition of portrait painting, including that of Gainsborough, Reynolds, Titian, Ingres and others. With a difference. Wiley has taken a form that was used primarily in the service of the wealthy and privileged and populated his canvasses with black and brown individuals, primarily men. The visual vocabulary remains the same. It is the subject of focus that Wiley has altered. Postures of power and physicality are now embodied by young men he found on the streets of Harlem, Senegal, Dakar, and Rio de Janeiro.

Presented here, side-by-side, are Wiley’s A Portrait of a Young Gentleman and Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy. Gainsborough had originally titled his painting A Portrait of a Young Gentleman. Popular discussion of the painting soon referred to it as The Blue Boy, and by 1798 that nickname became its official title.

Wiley proudly embraces a centuries’ old painting tradition. As proudly, he embraces an emergent reality: the power of people of color. He has reimagined a classic form of Western European painting in the service of a very 21st-century world. His artistry displays that breaking continuity can sometimes be the best way to maintain it.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday December 29 as we explore estrangement and unity.