Lorraine Hansberry is best known for her play “A Raisin in the Sun,” which debuted on Broadway in 1959. The title is based on lines from the poem “Harlem” by Langston Hushes: “What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?” The play has achieved the status of a classic in American theater. It was nominated for four Tony Awards, was made into a film, has been the subject of numerous revivals, and was turned into a musical in 1973, for which it won the Tony for Best Musical.

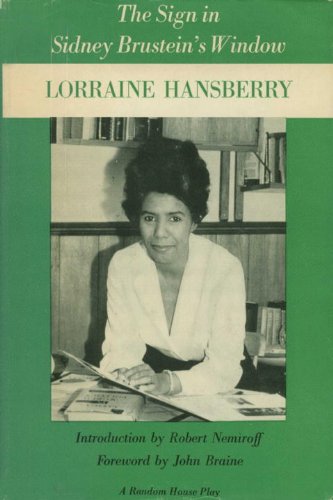

Five years later, in 1964, Hansberry wrote “The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window.” The play focuses on characters in bohemian Greenwich Village of the early 1960’s struggling to address a multi-verse of social justice issues while simultaneously trying to make sense of their personal lives. Unlike “A Raisin in the Sun,” “The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window” fell into the shadows of American theater.

This month a production of it began performances at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. It stars Rachel Brosnahan and Oscar Isaac. In an interview with the New York Times, both actors responded to a question about what surprised them about the play. Isaac answered: “Every character has moments of extreme selfishness, ignorance and ugliness. Then, within a sentence, they say something that breaks your heart.” Brosnahan added, “She [Hansberry] gives each and every character the grace to be exactly who they are.”

I lingered for a long time over Brosnahan’s association of the notion “grace” with an author’s permission for a character to be who they are. Is this not what also happens with Pharaoh? For the first five plagues, Pharaoh reveals his character by hardening his own heart; only after the sixth does the text state that God hardens Pharaoh’s heart.

What is the nature of grace in Jewish tradition? The Hebrew word for grace, chen, initially appears in the story of Noah: “Noah found grace (chen) in the eyes of God.” This is Torah’s first mention of Noah. What has he done to merit this recognition? Nothing, at least nothing that the text has brought to our attention.

The word chen also appears in the Exodus story: “And God gave the people chen in the eyes of the Egyptians.” Is grace then an unconditional gift from God?

As Jewish educator Candace Kwiatek noted in a 2015 article in The Dayton Jewish Observer, “In Christian theology, grace is the unearned, undeserved divine gift of unconditional love, mercy, favor, acceptance, forgiveness, sustenance and salvation from God through Jesus to those who accept him as messiah and savior.”

The early rabbis developed a more tension-filled notion of grace. In the Talmud and midrash they explain that God created the world with both grace (lovingkindness) and justice (judgment). Lovingkindness alone would have opened the floodgates to all sorts of destructive behavior. Justice alone would have too harshly condemned all of creation. God’s favor is not automatic, according to the rabbis, for that would undermine justice. Nor can one earn God’s grace because that suggests human capacity to control God.

Kabbalah further developed the necessary tension between grace and justice. In the kabbalistic system of the sefirot, the emanations through which the Source of all life makes itself known in the world and within each human being, the attributes of judgment/justice and grace/lovingkindness are portrayed as opposite one another. They are in a dynamic relationship. Each needs the other in order to achieve some measure of balance and harmony.

The characters in “The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window” are flawed human beings engaged in acts of artistic creativity, political activism, and personal intimacy. Some tragically fail in their ability to overcome their own biases and lose love. Others are crushed by the judgment of others and lose their own lives. At the end of the play the two main characters, Sidney and his wife Iris, seem to overcome the bitterness and bickering that has characterized their life over the course of our time with them. They embrace as the sun rises. The play concludes, even as we know that for Iris and Sidney new scenes will be written, ones which the author has given them the grace to write themselves.