To be both at home and on the way home is a spiritual practice for a meaningful life. The primary exercise is to hear, to still the clamor of fear, anxiety and anger. Hospitality to others is an outward expression of hearing. View the study sheet here. Watch the recording here.

In 1816 the Italian explorer Giovanni Belzoni purchased for the British Museum a colossus statue of Ramesses II, known by the Greek name Ozymandias. Ramesses II reigned as Pharaoh of Egypt from 1279-1213 BCE. Some scholars believe that this is the pharaoh described in the book of Exodus.

The Ozymandias colossus was originally about 65 feet high and weighed about 1,000 tons. By the time it was discovered in 1816, all that remained was a torso and head, which stood 30 feet high and weighed 83 tons.

The following year, Percy Bysshe Shelley, inspired by the discovery, wrote his sonnet “Ozymandias.” Shelley allowed Ramesses’ voice to echo across millennia: “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” The mighty indeed despair…not at pharaoh’s power but at the recognition that their own power is ultimately transitory.

Jewish tradition views Pharaoh as a figure anxious about mortality and frightened by change and by the other. “Who knew not Joseph” was not a matter of ignorance or forgetfulness by Pharaoh. It was part of a strategy to maintain hegemony, by denying even the existence of the other. It is but a short distance, a matter of a few verses, from that denial to planned genocide.

Torah is aware that to live in Pharaoh’s culture is to all too easily absorb that pervasive fear of change, wonder, and openness to discourse and adaptation. In this week’s portion, Ekev, it challenges the Israelites to choose between a path of curses and one of blessings by reminding them of two incidents: that of the golden calf and that of manna from heaven.

The golden calf was constructed by the Israelites out of their anxiety about absence, impermanence. Manna is a term both for the physical substance that the Israelites gather and for their expression of wonder at seeing it: mah hu? (“What is this?”). The golden calf was easily ground to dust. Questioning would be their true sustenance.

R.B. Kitaj was an American artist, whose life was shaped by a series of dislocations and losses. Born to Jewish parents in 1932 in Chagrin Falls, Ohio, his father abandoned him and his mother shortly after his birth. He moved to England to study art and travelled back and forth between birth and adopted homeland throughout his life.

Kitaj’s first wife, Elsi Roessler, committed suicide in 1969. He remarried in 1983 to Sandra Fisher, who died suddenly in 1994 from an inflammation in the brain. Kitaj, however, blamed her death on a savagely critical review of his retrospective at the Tate that year. In 2007, eight days before his 75th birthday, Kitaj committed suicide.

Hannah Arendt’s reports on the trial of Adolph Eichmann shattered Kitaj’s sense of what it meant to be a Jew. “I had really believed that I could be a Jew only if I wanted to be a religious one; if not, not.”

“If Not, Not” became the title for Kitaj’s visually expressed confrontation with the Holocaust. Inspired by T. S. Eliot’s poem “The Wasteland,” it displays a scene of cultural disintegration, moral collapse, murder, and…a self-portrait of himself holding a baby. An image of the insistence to live in a scene dominated by shatterings.

Kitaj struggled with how to integrate his reawakened Jewish identity into his art. He said that he was not interested in “dancing Hasids and Menorahs and flying cows.” There was something deep and profound and unsettling from the Jewish experience that needed to be brought to the canvass. A message that was both disruptive and redemptive.

He concluded that the major contribution the Jewish people brought to art was the contending dynamic between home and exile. In 1989 Kitaj published First Diasporist Manifesto. The Jewish encounter with the world, Kitaj wrote, is shaped by a promise of home within a reality of ongoing wandering.

This produces a sense that settledness, whether of place or of meaning, is transient. Kitaj identified a Jewish artistic sensibility: that of living engagingly within a world while eternally searching for another. Truth is never final. Indeterminacy explains more than complete clarity.

In his Manifesto Kitaj describes as the Diasporist artist one who “lives and paints in two or more societies at once.” This artist gives expression to meanings which refuse to be settled, at home, or stable. All creative expressions are open to dialogue, negotiation and ongoing interpretation. Such indeterminacy is a gift to a world threatened by the death that results from absolutism and certitude.

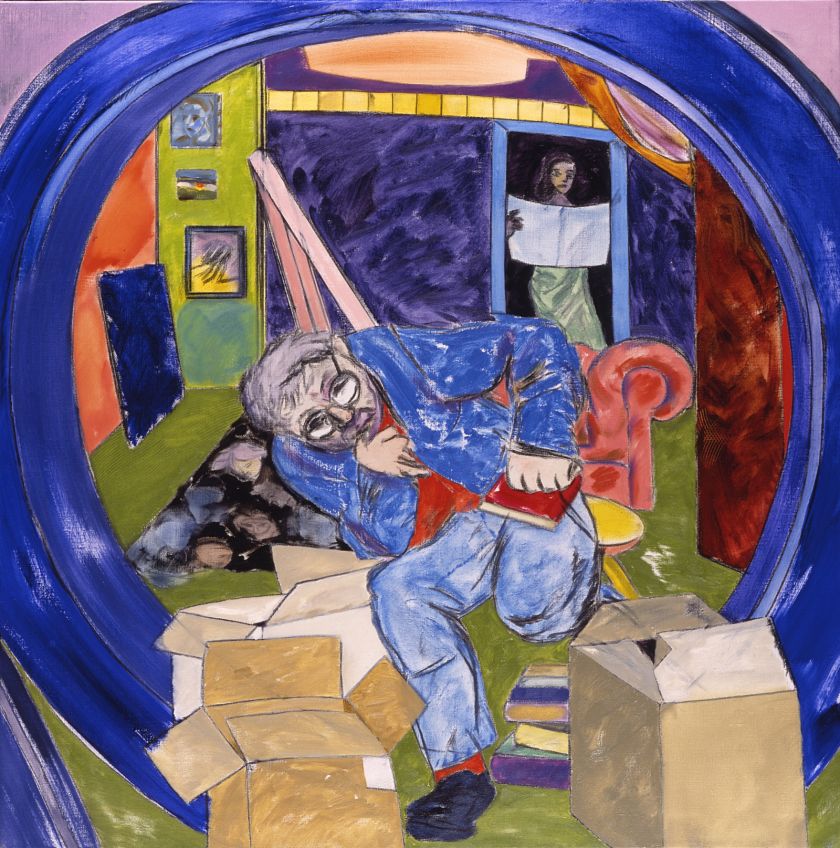

To the written text of his manifesto, Kitaj produced a visual analog, Unpacking My Library, which is pictured here. In the foreground is Kitaj in a cluttered interior space, surrounded by boxes, books and paintings spilled out across the room. His posture is a combination of Rodin’s sedentary Thinker and a classic Greek statue of a runner. He is at home and set to go. There is the linearity of forward movement and the circularity of constant return.

In the Bible, narrative privilege is given to nomads, shepherds, of which Abraham is the iconic figure. He travels, settles temporarily and travels more. He watches over his flock and opens his home to the sojourner. The purpose of ongoing journey is to experience humility in the face of the infinite and to see the infinite in the face of the most humble.

Kindness is the currency of the one ever on the way. “A Diasporist,” Kitaj wrote, “will find new ways to make pictures stand up for these old instincts [of goodness and kindness] in a world gone hateful again…”

Every day we too are offered paths of blessings and paths of curses. We can choose to construct colossuses or focus on the wonders and ask about their source. The former erode and crumble. The latter sustain us as we continue ever on the way.

Join us here at 7:00 p.m. (PT) Thursday, August 3 as we explore to be ever on the way.